Editor’s note: In many countries the word “kaffir” is an ethnic slur. While the etymology of the term is debatable, it may have originated from the Arabic word kafir, which means “infidel” or “unbeliever.” More recently, within apartheid Africa and India, it was used to refer to the native black population in a derogatory manner. It is particularly offensive to Black South Africans, and there is a strong movement, with a valid argument, to ban the use of it entirely. We do not wish to offend anyone, however in the United States, the term doesn’t overtly carry these negative connotations. The “k-word” is still widely used to refer to the fruit in the culinary marketplace. Other possible names include wild limes, Thai limes, and a non-offensive alternative that has been adopted is the Thai word, Makrut.

Read more ‘food for thought’ on the controversial nomenclature in the following articles. We thank our readers who have brought this to our attention.

Is the Name Kaffir Lime Racist? and Why the Name ‘Kaffir Lime’ Is Wildly Offensive to Many

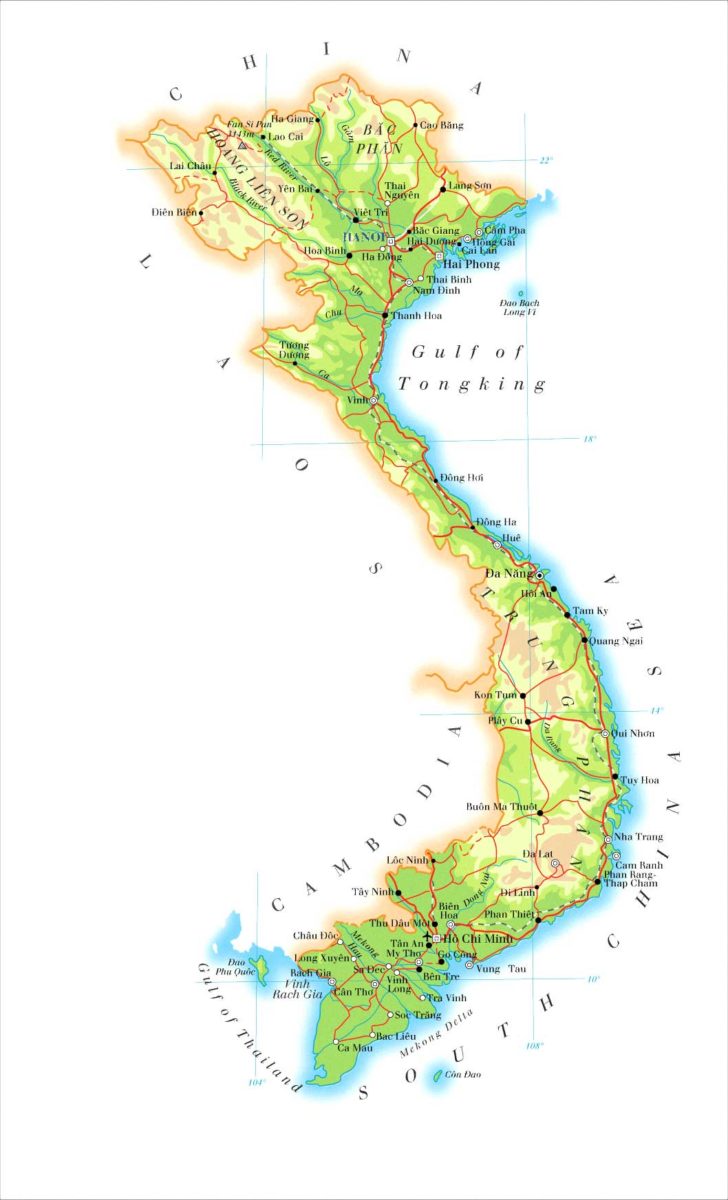

I can’t remember if the Kaffir lime tree, a truly inspired Christmas gift on my mother’s part, came after my father visited me in Yangon, Myanmar or if it was after the three of us saw Angkor Wat together. Either way the tree transformed the way our household ate. My father has always been an experiment-prone cook who relishes tinkering with traditional American recipes. I can still remember the day he “baked” chocolate chip cookies in the smoker, the night he singed off all of his arm hair flash-roasting a slab of salmon in the Big Green Egg. When I moved to Vietnam in my early twenties, the circumference of my father’s culinary inspiration expanded exponentially.

At the holidays I would stuff my suitcase with medicine balls of date sugar, white Thai pepper, and pungent teas to satisfy his appetite for the exotic. For him, tasting the various flavors of the far-away country I called home lessened the distance between us. Few ingredients are truly indispensable for authentic South East Asian cooking and Kaffir lime is one. You can make a heady Tom Yum Goong soup with Kaffir limes leaves, with the zest of the skin a pungent Kaeng Kiew Wan Moo green curry. Steep the leaves in simmering coconut milk and their luscious perfume will, with ease, elevate an already foreign flavor to the realm of the otherworldly.

The leaves are difficult to find at North American grocery stores and the fruit itself near impossible. So my mother special-ordered a Kaffir lime tree from a nursery in Georgia. We were all a bit skeptical of the citrus tree’s ability to survive a typical New England winter. But survive it did. The first year the tiny white nectary blossoms arrived in spring and the fruit quickly followed. A bit like miniature osage oranges, the limes appeared shriveled and bumpy, forking out at funny angles from the glossy, dark double-lobed leaves. That summer my father discovered shrimp cakes and rice noodles; that winter, an arsenal of delicious, rich, coconut milk based soups.

In tropical South East Asia, almost every rural home has a Kaffir lime tree in the yard. Its uses are seemingly endless. Need something to rid your favorite shirt of an oil stain? Sprinkle some Kaffir lime juice on it with a bit of detergent. A tonic to ward off evil spirits? Simply break a few Kaffir lime leaves and let the pungent oils they release do the rest. A natural antiseptic, the oil from a Kaffir lime is used to clean the house and is also spread on cuts to kill bacteria. Like lemongrass, ginger, and galangal, the Kaffir lime is a great digestive aid. In a tropical climate where food can turn fast and a stomach even faster, Kaffir lime is part of an everyday holistic approach to health.

I can still remember the Tom Yum Goong soup I ate regularly when working on a book about the re-appropriation of colonial city space in downtown Yangon. Just down the alley from my guesthouse in the center of town there was a beer joint where all the local men gathered. After long days lugging a twenty pound pack of tilt shift lenses, my Canon F1, and thirty rolls of slide film up and down stairs to capture an image of the inside of a long-inhabited, soon-to-be-bulldozed, Fin de siècle home, I was always thrilled at the prospect of putting up my feet, drinking a beer and slurping down a big bowl of soup. The Tom Yum Goong at this watering hole was in no way traditional – it had tofu instead of shrimp, was packed with various vegetables, and always a few creamy quail eggs floated just below the surface. It was everything traditional Tom Yum Goong was not – haphazard and over-full.

I can still remember the Tom Yum Goong soup I ate regularly when working on a book about the re-appropriation of colonial city space in downtown Yangon. Just down the alley from my guesthouse in the center of town there was a beer joint where all the local men gathered. After long days lugging a twenty pound pack of tilt shift lenses, my Canon F1, and thirty rolls of slide film up and down stairs to capture an image of the inside of a long-inhabited, soon-to-be-bulldozed, Fin de siècle home, I was always thrilled at the prospect of putting up my feet, drinking a beer and slurping down a big bowl of soup. The Tom Yum Goong at this watering hole was in no way traditional – it had tofu instead of shrimp, was packed with various vegetables, and always a few creamy quail eggs floated just below the surface. It was everything traditional Tom Yum Goong was not – haphazard and over-full.

I knew my father would like this unorthodox soup and so when he came to visit I brought him to the beer joint his first night in town. Over a heaping bowl of what I called “Everything in the Refrigerator Tom Yum Goong” we unpacked the day’s proceedings.

“Tell me why you love this place?” my father said to me that first night. In those days, Yangon’s power supply was often cut at dusk. What little light remained came from generators and candles. The darkness was so near complete it made me want to whisper my reply. We had spent the day walking – down the Strand and through the old center of town where hundreds of colonial buildings were slowly being eaten away by dampness and mold. Soon the country would open and these buildings would be demolished to make way for skyscrapers. But for the time being what remained – such worn, reedy evidence – was, to me, a poem in architecture, written at the intersection where time meets material. I told my father as much, that I appreciated what Yangon literally stood for – for the quiet dignity with which the city’s residents went about building their lives in the shell of an abandoned empire.

Dad thought this over for a minute. I nudged a quail egg towards the cup of his ceramic spoon. The darkness licked at the beer hall’s stoop and the kaffir lime in the soup quietly cleansed our tongues. Yangon was thinner than any city my father had ever seen before. Not quite as thin as a house of cards, but close. I knew then that he would be unable to romanticize Yangon the way I had. He told me this much. I imagine that when I have children of my own I will understand his resignation more fully.

When my father returned to the United States he started making his own variation of “Everything in the Refrigerator Tom Yum Goong.” It reminds him of the vastness of the world and the daughter he released into it.

I have been back in America for five years now, and dad’s Kaffir lime tree is as healthy as ever, which is still hard for me to fathom given that they live in New Hampshire where the average temperature in January is 20° F. My father continues to experiment. Recently he passed along a recipe for Kaffir Lime Pie. More floral than key limes, the Kaffir limes make the original seem a poor imitation of a much more complicated set of flavors. Inspired by my father’s recipe, I recently held a Kaffir lime dinner party. The menu is below: “Everything in the Refrigerator Tom Kha Gai” (a new take on the old standby) and “Dad’s Kaffir Lime Pie”. Outside the Brooklyn streets filled up with snow and emptied of people, while inside we let the delicate flavor of the Kaffir lime carry us momentarily to warmer, worldly climes. ![]()

Citrus hystrix, called the kaffir lime or makrut lime, is a citrus fruit native to tropical Southeast Asia and southern China. Its fruit and leaves are used in Southeast Asian cuisine and its essential oil is used in perfumery. Its rind and crushed leaves emit an intense citrus fragrance.— Wikipedia