I suspect that Châteauneuf-du-Pape may be the first of the “great” French wines that many people buy, because, while its name may be the most French they can speak in one “phrase,” it somehow rolls off the tongue — it virtually sings itself into the glass — and it sounds sophisticated.

This was certainly the case with me. I don’t remember the specific bottlings, but I do know that I would order Châteauneuf-du-Pape in restaurants before I would learn enough to order other fine wines. I do remember being proud of my (silly) self when I would say, “The Châteauneuf-du-Pape, please.” Except I said de and not du and would continue to for years, unknowing, unsophisticated despite my attempt to be otherwise.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape got its name from the time, early 14th century, when the papacy moved, essentially, from Rome, Italy, to Avignon, France, where it stayed for the next 69 years, through 8 popes. The first of these was Pope Clement V, who was a great lover of wines; he drank and studied wine not only in the southern Rhone but also in Burgundy and in Bordeaux, where today his name lives on in Château Pape Clément, the oldest wine estate in all of Bordeaux. The next pope, John XXII, was an even greater proponent of the local wines and erected a new castle and began planting vines soon after he became pope in 1316. The wines then were actually known as Vin du Pape.

The name of the wine means The New Castle of the Pope. But this name was not used until the very late 19th century. Until then, there was no wine named Châteauneuf-du-Pape. It was called Châteauneuf-Calcernier, after the existence of a limestone quarry and lime kilns in a nearby town. If anyone out there has a bottle of Châteauneuf-Calcernier, it will certainly qualify as an Odd Bottle.

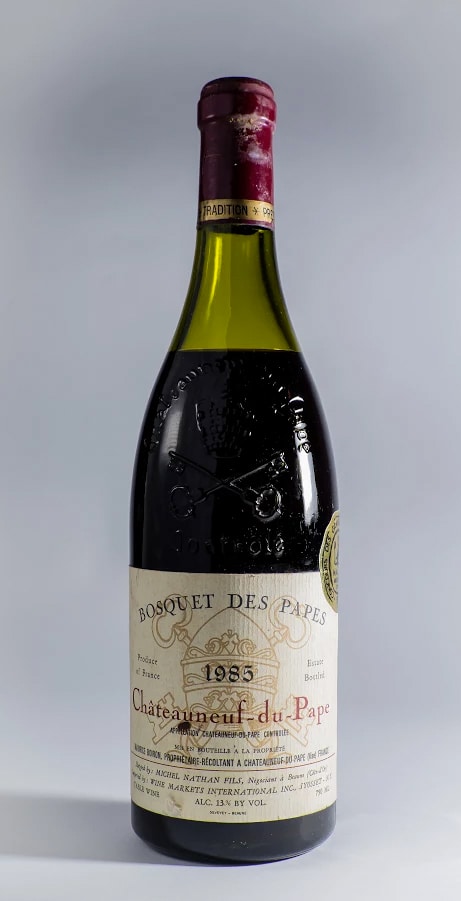

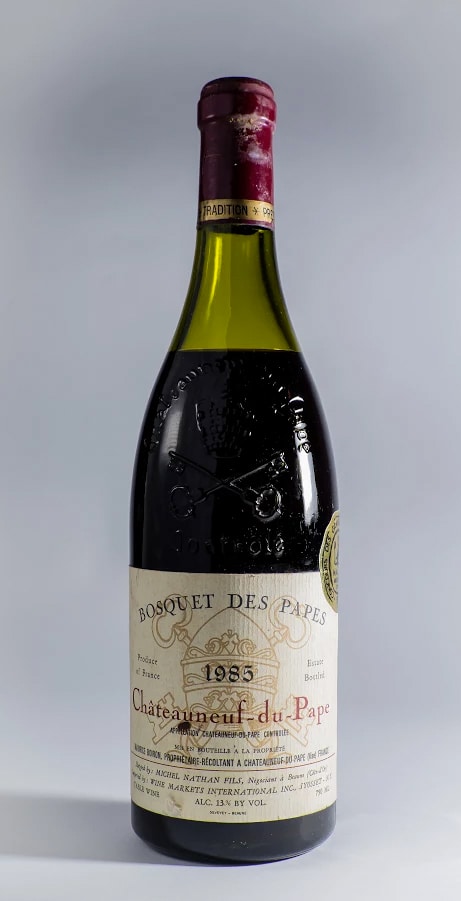

Châteauneuf-du-Pape red wines (there is also a white CDP) may be blended from as many as 18 different grapes, but most consist primarily of Grenache, Syrah, and Mourvédre. Our 1985 Bosquet des Papes is 70 percent Grenache and 10 percent of the other aforementioned and another 10 percent of Cinsault.

What’s most distinctive about the creation of the wine are the vineyards, which are virtually drowned in stones of all sizes. There is little or no soil visible beneath the stones, but it’s there. It’s a varying (vineyard by vineyard) mixture of limestone, clay (both red and gray), sand, and marl.

And what the stones do for it is to hold, while at the same time hold off, the extreme heat of the area and also to keep what moisture has entered the soil, around the stones, from evaporating too quickly.

The wine that results from this distinctive landscape is said to taste of stone and earth; of mineral and (in the best sense) dirt.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape got its name from the time, early 14th century, when the papacy moved, essentially, from Rome, Italy, to Avignon, France, where it stayed for the next 69 years, through 8 popes. The first of these was Pope Clement V, who was a great lover of wines; he drank and studied wine not only in the southern Rhone but also in Burgundy and in Bordeaux, where today his name lives on in Château Pape Clément, the oldest wine estate in all of Bordeaux. The next pope, John XXII, was an even greater proponent of the local wines and erected a new castle and began planting vines soon after he became pope in 1316. The wines then were actually known as Vin du Pape.

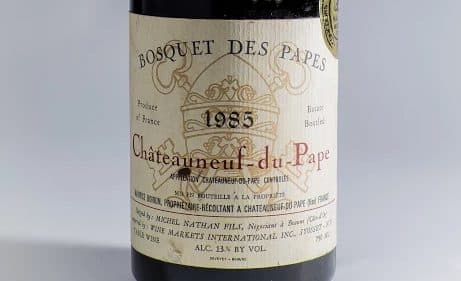

I had been worried about my 1985 Bosquet des Papes because of the ullage in the bottle. Ullage (pronounced ull — rhymes with hull, not with full — idge, emphasis on the first syllable) means, in a sense, the nothing that’s there: the wine that’s missing from the bottle. The ullage in this wine is apparent in the accompanying photo. If you picture the wine having once come almost to the bottom of the cork, you can see that a good deal of it has become what is called, more often in whiskey-making and referring to what liquid is lost through evaporation, the “angel’s share.” Ullage can also occur because of leakage through the cork (caused usually by excessive heat), and this leaves a wine bottle ugly with label-stain and the wine at risk of oxidization.

As it turned out, the ullage here meant only that there was that much less to drink of this wonderful wine.

The cork, after some 30 years in the bottle, broke in two and then shredded. None of it remained in the bottle. If it had, I would have decanted the wine. I try never to decant wine for this column, because I like to taste the wine over several days to track its evolution. And decanted wine matures much more quickly.

As it turned out, the ullage here meant only that there was that much less to drink of this wonderful wine.

The cork, after some 30 years in the bottle, broke in two and then shredded. None of it remained in the bottle. If it had, I would have decanted the wine. I try never to decant wine for this column, because I like to taste the wine over several days to track its evolution. And decanted wine matures much more quickly.

In this case, I probably should have decanted the wine anyway, because, though it had been standing for several days and showed no sediment when I looked through the bottle against a strong light, the wine was

In this case, I probably should have decanted the wine anyway, because, though it had been standing for several days and showed no sediment when I looked through the bottle against a strong light, the wine was definitely cloudy from the first pour. And yet despite whatever particulate matter may have been clouding the wine, it took away almost none of the wine’s core of bloody beauty. This faded to gold at the edges in the glass but was still much younger in color than I had expected it to be.

It was fully integrated on the nose. There was a sweet fruit in the tasting of the wine, with an edge of earthy incursion, and this created a perfect balance between light and dark. As in the look of the wine, so in the taste.

It more than held its own — and held me captive — with rare rib-eye steak.

Most wine experts agree that CDP wines should not be aged for more than 12 years.

Robert Parker, in his first (1987) edition of The Wines of the Rhone Valley and Provence, said this 1985 Bosquet des Papes appeared to be one of that vintages top CDP wines and would plateau in 10 years.

Almost 20 years after this wine streamed onto that plateau, it proved to be both youthful and mature. But imagine my surprise when I came back home after over a week away and found the bottle where I’d left it in the refrigerator door and, after it had warmed up, poured out the little that was in it and held my nose (from the inside) and took a sip. Still fine, not only drinkable but stunning. It was a miracle! But, then, the world of wine probably provides more miracles than does any other world. If you believe in that sort of thing. ![]()

First published February 2017