Lessons from a Generous Wine Snob

"…the absolute best wines for food…no grape, white or red, goes better with more foods than Riesling.”

The first Riesling I ever drank

was given to me by my first literary agent (poor guy), Bob Lescher, who was, by then, in the 1970s, a wine snob but a generous wine snob who loved wine even more than he loved snubbing those who either didn’t love it (sufficiently) or who didn’t know very much about it.

Bob Lescher represented the great M. F. K. Fisher. It was later that he came to represent Robert Parker, Robert Finigan, and other wine (and food) writers. And he wasn’t limited to gustatory arts. His clients included writers Robert Frost, Isaac B. Singer, and Madeleine L’Engle; artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Andrew Wyeth; and the Dalai Lama, invited by Lescher to become a client because, he said, Jesus already had an agent and he, Lescher, wasn’t going to poach him.

The bottle of Riesling he handed to me while I was taking him out to a long, fancy lunch (I was making a living not as an unpublished writer but as a publishing book editor, with an expense account) was a bottle of Trefethen White Riesling.

“Let me know what you think of this” he said.

“Now?”

“Not now, you fool.” Or something like that. “Take it home and try it.”

I did. It was wonderful. Truly. I was a bit afraid to tell Lescher (people always referred to him by his last name, as they eventually would to “Parker”) how good I thought it was because I didn’t trust him not to have given me a wine he didn’t like just to test how sycophantic or wrong-headed I might be.

But I gathered my courage and either wrote him or called him to give him my very positive opinion. His reaction was to send me (by messenger) yet another bottle of Trefethen White Riesling. (Lescher was a generous snob.) I was soon buying it by the case.

Not long after that, at another lunch, I brought him a bottle of wine I liked. Loved, in fact. It was an Aglianico, which is the name of a grape and of the wine made from it in southern Italy. I don’t recall which producer, though it may have been an Aglianico del Vulture, possibly from d’Angelo (some of which I still have on loan from the gods of wine).

It didn’t matter at that moment whose bottling it was, because Lescher didn’t seem to know the wine at all. He looked down at the bottle with his narrow reading glasses perched on the tip of his nose, squinted, and said, “We’ll see.”

Oh, did we see! Or smell, taste, and, probably, spit (not in an approved way).

The next time I spoke to him I asked if he’d enjoyed the Aglianico. He answered immediately and dismissively, “If I want to taste chocolate, I’ll buy a chocolate bar.”

Aglianico is celebrated for its chocolate accents, which, for most tasters, but obviously not for Lescher, couple pleasingly with the dark fruit buried in its rich nose and mouth-plumping texture.

Long after Lescher was no longer my agent (lucky guy), he and I continued to eat and drink together, over the years. But I never again gave him a bottle of wine. Nor did he give me one. But I’ll be forever grateful that he gave me that first bottle of Trefethen White Riesling.

By now, some forty years later, I’ve drunk many Rieslings. But not nearly enough of them. If I’d tried more, I would probably have no reason whatsoever not to agree with the “significant number of wine writers and experts” who, as Oz Clarke writes in his indispensable Grapes & Vines, “repeat their view that Riesling is the greatest white grape in the world.”

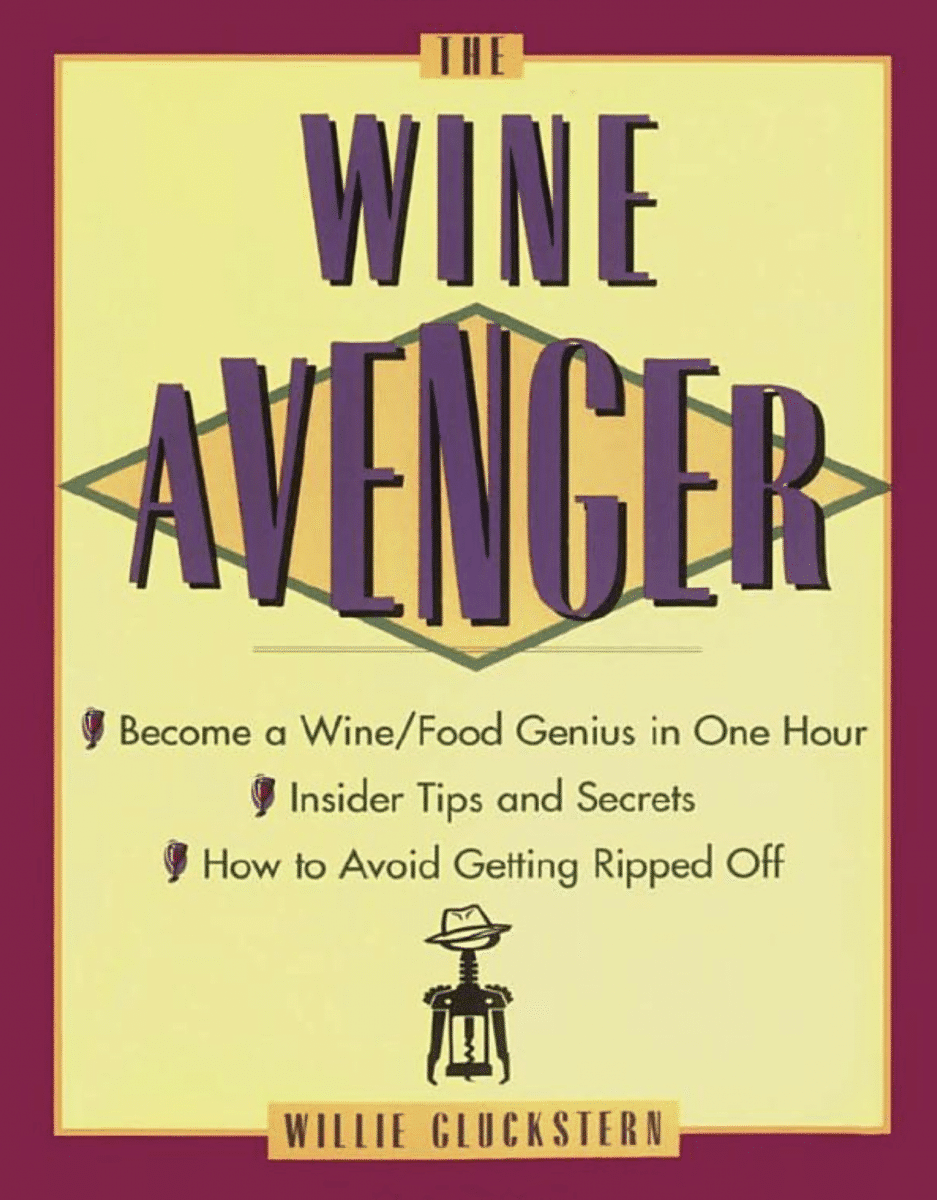

Willie Gluckstern, in his delightful and informative book The Wine Avenger, doesn’t come right out and say that Riesling is the greatest white grape in the world. But that’s because he has another way (ways, actually) of saying it.

His first words in his Riesling chapter are inviting and inspiring: “The defining moment in your vinous evolution has arrived. It is time to meet Riesling. All other grape varieties are merely a prelude to the wonder of this small, fine berry….Riesling is the world’s most important wine grape.”

So, you see, not explicitly the greatest. But, yes, the most important. Of any color.

The importance for Gluckstern comes from Riesling’s compatibility with food. As he says, the grape “creates the absolute best wines for food…no grape, white or red, goes better with more foods than Riesling.”

He also says that no grape produces “more ethereal, complex aromatics.” Or can be made in so many different styles (very dry to very sweet). Or, as a white wine, can age so “magnificently.” Note he doesn’t say, age so extendedly. I suspect that Chenin Blanc would win that battle, not that wines should fight, or even contend, for such honors. Nor should those of us who love great wines make a contentious case (no pun) for any—wine is a celebration, not a campaign.

No other wine, says Gluckstern, is (ring the terroir bell), “more transparent in the expression of the soil in which it grows…no matter where it’s grown.”

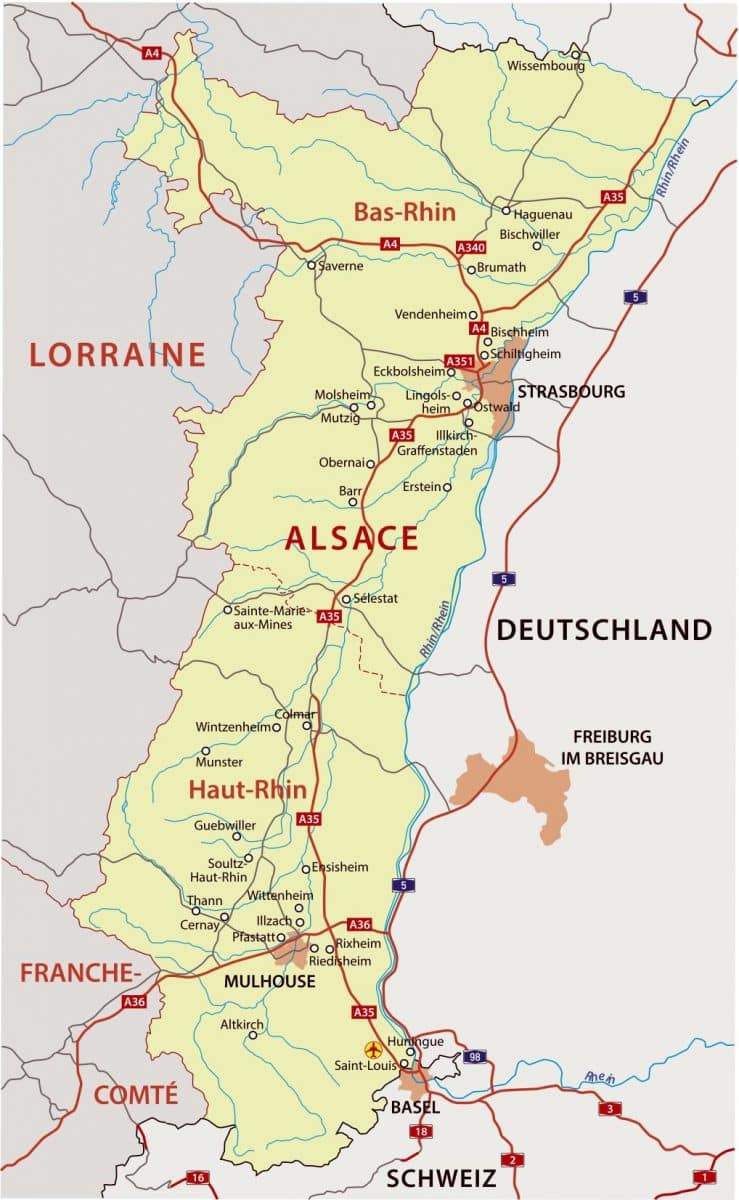

It becomes clear, in reading Gluckstern on Riesling, that he’s referring primarily to German Rieslings. And our Odd Bottle is not German, it’s Alsatian.

In Alsace, the soil is mostly clayey, calcareous, which contrasts with the slate in much of German wine territory, and this provides Alsatian wines with a fuller body. Alsatian wines spend more time in old barrels, which fills them out. They become, to continue with what Oz Clarke has to say about such national differences, “rich, honeyed and petrolly in maturity.” Clarke advises aging them, depending upon their style, from three years minimum to decades for the sweetest expressions.

Alsace, as Gluckstern reminds us, lies on the French side of the France/Germany border. And for him these wines, produced in the French, not the German, style, are full-bodied, high in alcohol, usually quite dry, earthy in a way that German wines might be declared heavenly.

There are many human beings who would rather live on earth than in heaven, as there are those who would rather drink Alsatian Rieslings than German. I say, live on earth and keep a vacation home in heaven. Drink Rieslings from both countries in both your domiciles. And don’t forget to eat.

Jancis Robinson calls Riesling “the uncontested queen of Alsace.” She says it “has a steeliness that makes it quite impossible to confuse it with a German wine.”

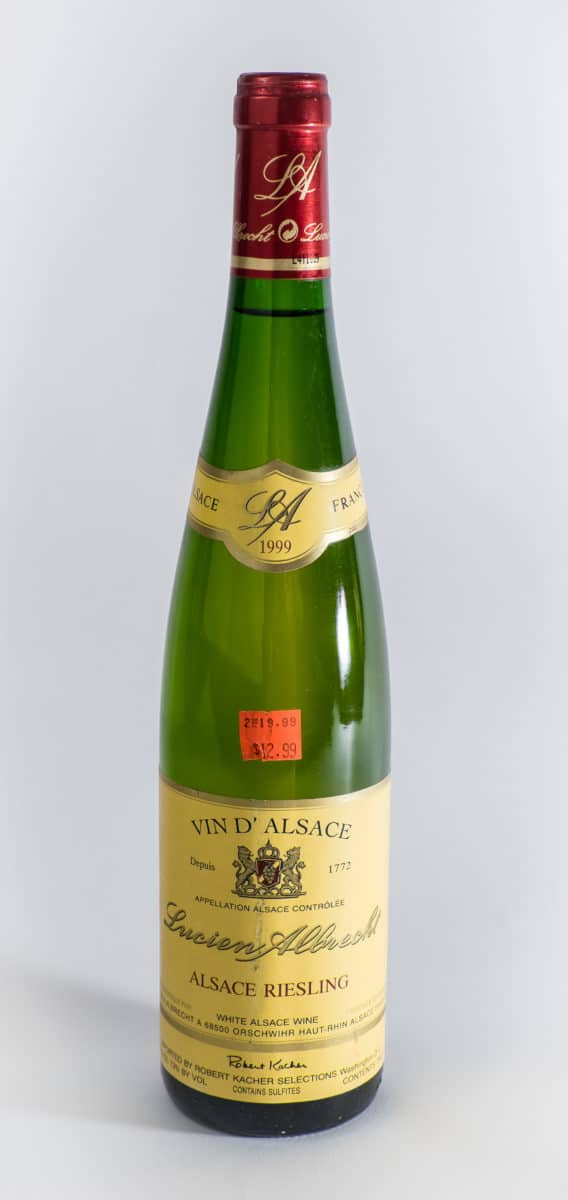

Our 1999 Lucien Albrecht Alsace Riesling is from one of the lesser known Alsatian wineries and is the modest kind of wine that would be (and is) featured on The Reverse Wine Snob.

The winery is older than many in the United States. Make that, in the world. It was founded in 1425 by Romanus Albrecht. Same family! I’ve amused myself with imagining a vertical tasting of wines from all the nearly 600 vintages (or at least years) since Albrecht’s founding. (Only the sweetest might have survived.)

The 16th century was when the wines of Alsace first came into their own, through the founding of the Winegrowers Guild of Alsace. Eight generations of Albrechts led this guild between 1520 and 1698.

Albrecht is perhaps best known for its Crémant d’Alsace, which is a sparkling wine made from various Alsatian grapes and is produced by the méthode champenoise and has become, after Champagne, the most important sparkling wine in France. Albrecht was, in 1972, one of the major founders and innovators of Crémant d’Alsace

I purchased my bottle of the winery’s 1999 Riesling some short time after the turn of the century, at a wine store in Newburyport, Massachusetts. I could have paid $12.99 for a single bottle of it, but it was being offered at 2 bottles for $19.99, the sort of deal I have never once passed up. (Not that I always should have taken it.)

I drank the first bottle some years ago and kept no record of it. I drank the second only recently, with the intention, if I felt it was worthy, of writing about it for The Odd Bottle.

Clearly, it was.

All it said on the cork was, “Mise En Bouteilles en Alsace”—no producer or vintage. The cork in this almost 20-year-old wine came out in such fine shape that it might have been inserted only in the latest vintage.

The color was pale gold, almost pinkish. This was the result, almost certainly, of the wine’s relatively (for the kind of wine it was) advanced age.

Swirled in a smallish, white-wine designated glass, the wine was very aromatic. There was only a slight, and actually rather appealing, hint of oxidation on the nose.

There was a great deal of fruit on the tongue. And an unexpected hint of sweetness and less minerality than I’d expected. I might easily have identified this as a white Burgundy (i.e., Chardonnay).

But maybe that’s just me–because perhaps never in history has an Alsatian Riesling been confused with a Burgundy.

Well, it has now. (Or almost.)

There was a great deal of fruit on the tongue. And an unexpected hint of sweetness and less minerality than I’d expected. I might easily have identified this as a white Burgundy (i.e., Chardonnay).

And then…a stupendous aftertaste. I wrote almost all the above notes about the wine (by hand), and I realized that the wine was still vivid in my mouth, all over my mouth, like a coating of some paradisiacal fruit, drunk in the Garden of Feedin’ (and Drinkin’).

Later, but before the wine was drunk with any food, it showed in the mouth a kind of a kind of candied essence. Candied, not sugary.

It was then served, rewardingly, with pan-fried tilapia, roasted potatoes, salad with Caesar dressing (no anchovies, alas). I was wary of the wine with the salad dressing. The wine probably knew that and grew wary of me for a while—the dressing and the wine had sufficient mutual tang to coalesce without conflict.

On the second day, there was a bit more pronounced oxidation in the nose, but the fruit still prevailed.

The wine was drunk with Chinese food. Many wine-pairing guides suggest Riesling with Chinese food, but most fail to tell you from what country the Riesling should be.

In this case, it was our Alsatian Riesling with, of all things, a beef dish (beef with ginger and string beans). The suitability of the combination of wine and this food spoke to what Willie Gluckstern wrote about Riesling’s going with more kinds of food than any other wine.

So, on the second day, the fruit did predominate in the taste, though the oxidation brought along with it a slight bitterness that seemed less like an assertion of acidity than a putting forward a tertiary flavor of an unbidden but not unbitten seed, perhaps apple (but not the pips, whose minuscule amount of cyanide has no taste anyway…says he, gasping for breath).

The wine was still vivid on the third day but not as tasty.

It was showing its age not so much in fading as in walking slowly away.

On day four, the fruit had pretty much faded, as had any acidic bite.

However, confusingly yet pleasantly, the wine showed less oxidation than it had even on its first day. I doubted this could be so, so I kept taking small sips of it over a period of several hours, sucking the liquid through my teeth (I am ordered to be alone in the kitchen when I do this). Still less oxidation than ever. Since the wine had been exposed to oxygen for four days (refrigerated when not being poured), I have no explanation for this except to theorize that what we call oxidation in terms of smell and taste is related not completely to how much oxygen to which the wine might have been exposed but to how the fruit in the wine presents over time. Fruit trumps air, we might say.

You can find the most recent vintage of this Lucien Albrecht Riesling (now with the word Reserve on it, which is meaningless) for an average of $15. If this wine was being retailed for $12.99 in, let us say, 2001, then it’s less expensive now, adjusted for inflation, than it was then, since that $12.99 would be just about $18.00 now.

A “rare” (wine critic term, not advertising) Crémant Rosé from Albrecht can be found online for $12.49.

Over 20 years ago (1994), Frank Prial, writing in The New York Times about a tasting of eight vintages (from 1973 to 1993) of Trefethen Chardonnays, said, aiming at my own heart, “Most good wine is consumed too early. It should get more time in the bottle even after it is sold at retail, but few consumers can resist opening and drinking it. As a rule, the Trefethens’ wines, which de-emphasize oak, really need more time in the bottle.”

Our Odd Bottle Riesling may prove that point (Rieslings aging much better than Chardonnays anyway).

Trefethen Rieslings may now say, “Reserve,” on the labels, but they no longer say, “White Riesling.”

I’d been planning to write in this Odd Bottle column that Trefethen labels should never have said White Riesling, because all Rieslings are white, and the reason Trefethen must have done that for so many years was because they didn’t trust the American wine consumer to know that Riesling was a white wine.

But I decided to check before I started sounding like a snobby wine elitist (which, like Lescher, I am). And what did I find (and thereby got to save what reputation I may have)?

There is a red Riesling (Roter Riesling). It’s a clone of white Riesling, with a pinkish skin, like that of theTraminer grape. It makes a white wine, not a red wine. Most wine scientists believe it evolved from the white Riesling grape. But there are those who believe the red Riesling came first.

So, you see, wine is a mystery: deep (or shallow) in the soil; out in the vineyards; sucked into test tubes; but, primarily, in your glass and then in your lucky (most of the time) mouth. ![]()

All it said on the cork was, “Mise En Bouteilles en Alsace”—no producer or vintage. The cork in this almost 20-year-old wine came out in such fine shape that it might have been inserted only in the latest vintage.

The color was pale gold, almost pinkish. This was the result, almost certainly, of the wine’s relatively (for the kind of wine it was) advanced age.

Swirled in a smallish, white-wine designated glass, the wine was very aromatic. There was only a slight, and actually rather appealing, hint of oxidation on the nose.

There was a great deal of fruit on the tongue. And an unexpected hint of sweetness and less minerality than I’d expected. I might easily have identified this as a white Burgundy (i.e., Chardonnay).

But maybe that’s just me–because perhaps never in history has an Alsatian Riesling been confused with a Burgundy.

Well, it has now. (Or almost.)

"All other grape varieties are merely a prelude to the wonder of this small, fine berry….Riesling is the world’s most important wine grape."— Willie Gluckstern