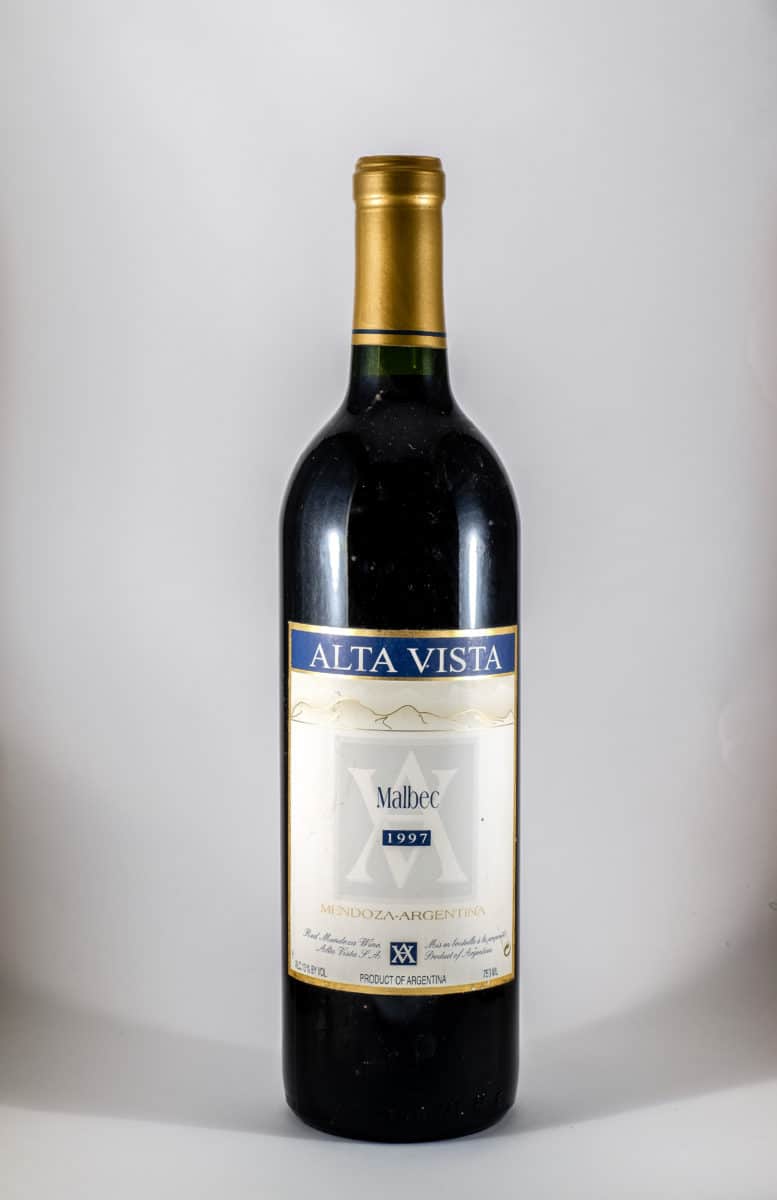

Grace and Generosity: 1997 Alta Vista Malbec Mendoza, Argentina

This 20-year-old Alta Vista is the first Malbec I ever drank and is not the first Malbec I ever drank.

Before I explain that silly riddle (if a riddle can exist without its being a question), I should say that this particular bottle of the 1997 Alta Vista is not my first. I bought several bottles soon after the vintage at good old Yankee Spirits in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, a natural, indeed almost necessary, stopping point for anyone driving between eastern New England and New York City.

After I’d drunk the first bottle — not long after its bottle shock (from the drive) would have been subdued — I was sufficiently taken with the wine’s perky brilliance that I stuck away a single bottle in a corner of my crawlspace so obscure (having no particular area or even shelf for wines from Argentina) that it took me nearly 20 years to come upon it, by which time I had become the odd Odd Bottle man and realized that I must open it now and find out if, like anything or anyone you once loved, it had remained constant in its grace and generosity.

As for its being, back then in the late 1990s, the first Malbec I’d ever had, it was the first wine called a Malbec, which is to say, my first varietally labeled Malbec. (Varietal is the word used to designate a wine made wholly or mostly from a single grape variety.)

I’d had a Malbec wine before. Oh, had I! I’d by then become a fan of wines from Cahors, an AOC in South West (Sud-Ouest) France. I think I was first drawn to it because it had long been nicknamed the “black wine.” This meant it was so dense with color that if you gazed through it in its bottle or your glass, you would see no light. You would see nothing but the darkness in the heart of this philosophically pessimistic wine. (If one may anthropomorphize a liquid.)

Yes, I was at the time a kind of existentialist-without-beret, a fan of deep, dark, inscrutable wines that matched the mood I believed was mirrored by, and in, the world itself.

Which is another way of saying, I hadn’t yet learned to let wines, never mind myself, mature before experiencing.

Speaking of berets, in Paris, a Cahors was always the first bottle of wine I ordered for our first meal (lunch) upon arriving, never mind jet lag and not having slept in 24 hours. It was at Domaine de Lintillac, now at 10 rue Saint Augustin (near the Bourse), where they still serve food of the South West, mostly duck. Indeed, if you look up the restaurant on Yelp, you’ll find that a customer has, under a headline DUCK GALORE, posted a large photo of a bottle of Cahors, Chateau La Caminade (Malbec, blended with a bit of Merlot).

Not that I would have worn a beret in Paris. But I did drink a few Cahors, there and in New York City. And I probably would have drunk more of them if I hadn’t been embarrassed at not knowing how to pronounce Cahors, which I think may be the most difficult short-wine-name there is to say correctly. (Check out YouTube, where there are at least 5 different pronunciations of the word from French speakers on posts that are meant to teach you how to pronounce it.)

So I drank a few Cahors (Cahorses?), likely Château de Haute-Serre, Château du Cèdre, the much available Clos La Coutale, and, later, Clos Triguedina. What I didn’t know right away was that these wines were…Malbecs! Or at least, by regulation, 70% Malbec. Except Malbec, in Cahors, was and is known as Côt or Auxerrois.

I should add, before we depart France for Argentina, that Malbec is called Malbec in France only in Bordeaux, where it is used in very small quantities in some blends. There is even a Chateau Malbec, but it uses only a minuscule 4% Malbec in its blend, and, in what might be taken by the grape as an insult, if grapes weren’t so generally good-natured, Chateau Malbec is named not after the grape but after one of its owners, Louis Malbec. (Lucky for him, I suppose, that he wasn’t named Louis Auxerrois. Lucky for the rest of us.)

Nowhere in France is a wine made from any amount of Malbec, even 100%, called Malbec.

Which is why the first Malbec I ever drank that was not the first Malbec I ever drank was our very own 1997 Alta Vista Malbec, from, as its back label says, “near Mendoza, in the Agrelo district of Luján de Cuyo appellation…our home away from Bordeaux.”

When I first sniffed and then sipped this 1997 wine in 2017, I said aloud, “Bordeaux.” (Don’t worry, for while I was addressing myself, there was someone else in the kitchen. Not that some wines don’t have you talking to yourself. Or to the wine.) This was before I’d read the back label. When I then read the back label, I was quite proud of myself: Bordeaux, indeed. The wine reminded me — with its fruit, smoke, and earthiness, all not so much modest as subtle — of an elegant Right Bank blend (and certainly not a strapping, fleshy Cahors).

I then discovered in Oz Clarke’s indispensable Grapes & Wines that Malbec was originally propagated in Argentina as long ago as 1852, with cuttings not from Cahors but from Bordeaux.

However, Oz Clarke finds the taste of Malbec more like a Carmenére and a Pinot Noir. I’m sticking with a more Merlot-based (Malbec-enhanced) Bordeaux.

This bottle’s typographically modest cork emerged in perfect shape after nearly two decades of fostering its maturing charge.

In the glass, the wine had clearly lost some color. I couldn’t remember how it had looked when I’d first tasted it years before. But there was no mistaking its having yielded some of its customary purplish-red (not “black” in Argentina) to the golden sunset of its lifetime.

It then provided, after the aforementioned sniff and sip, a lovely mouthful, distinguished, almost stately in its restraint and, at the same time, forwardness, like (if I may be forgiven for turning this into a gender-matter) an accomplished woman of considerable age with a resolute, substantial handshake.

The wine accompanied, that first night, a dish called, in the cookbook Dinner for Eight, Southern Italian Meatballs in Tomato Sauce. At the time I provided the wine pairings for that book, I had suggested Falerno, Cerasuolo di Vittoria, Laverano, Connonau di Sardegna, and Aglianico del Vulture. Clearly, I was trying to match the wines to the southern Italian origin of the dish. I’d like to think that if I’d been more geographically adventuresome, I would have suggested a Malbec. Because this mature Alta Vista was superb with that cheesy, tomatoey, pine-nutty, beef-rich culinary concoction.

I happen to have had open a bottle of 2012 Keiken Terroir Series Cabernet Sauvignon, which is 12% Malbec and 8% Petit Verdot, also from Luján de Cuyo in the Mendoza Valley. This wine, while 15 years younger than the Alta Vista, and certainly more vivid in appearance and forward in taste, suffered in comparison because it was less elegant and quite simple, despite its being a blend, whereas the Alta Vista tasted as if it emerged in layers, and it was the taster’s job to keep moving into its more profound depths.

The next evening, both wines were served with Bulgogi, meaning, in Korean, “fire meat,” which refers to its cooking method and not to what this dish turned out to be, because of the hot red bean paste with which it was served: too fiery (spicy) both for the older Alta Vista or even the younger Kaiken. So what did we drink (successfully) with it? A 2014 Covey Run Riesling from Washington State. Yes, an off-dry white wine with the spicy beef — amazingly suitable and tasty. And for those who think my wines are (sometimes) beyond their means, this Covey Run was selling for $3.49 at the New Hampshire state wine outlets. Under $4 for a white wine to accompany your Bulgogi — unheard of (until this very moment)! (I think.)

By the time the Alta Vista had been poured on this second day, it had been sufficiently consumed for lovely shards of sediment to appear clinging to the right shoulder of the bottle, where this sediment was to remain, undisturbed by further sloshing about of the wine (it was far too late to decant it), until the bottle was empty.

The bottle wasn’t empty until it had been drunk, as is the custom with Odd Bottles, for (at least) four days. So, with a dinner of sirloin (which had been used for the Bulgogi but was now served in filets and not in thin slices with a hot sauce) and another of dark turkey meat and a lunch of yet more of those meatballs, the wine lost none of its fruit (none!) nor of its suitability to these various dishes. Still graceful. Still generous.

The Kaiken never caught up to the Alta Vista. So when it was clear that the Malbec would soon be gone, I opened, for comparison, a bottle of a 2014 Bodega Catena Paraje Altamira Malbec, a single vineyard wine from perhaps the most highly regarded winery (Catena) in all of Argentina.

All I’ll say here, in respect of the winery’s founder, Nicolás Catena, is that I probably tasted this wine many years before I should have. I should have waited until it, too, was as old as the 1997 Alta Vista, which put to shame this prestigious Catena Paraje Altamira Malbec.

This odd bottle cost about $6 when I bought it in the late 1990s. In the most recent issue (December 2017) of Wine Enthusiast, the first 7 rated Argentine Malbecs cost $140, $140, $150, $115, $50, $50, $30. Then, at $20, comes a 2015 Alta Vista Estate, rated (ahead of 14 more Malbecs) 89. There exists a single-vineyard Alta Vista called Temis which costs about $50. There is also the equivalent of our odd bottle called Alta Vista Classic Argentina Malbec, which you can find for $9.

In other words, the wine is less expensive than when I bought some bottles almost 20 years ago. And kept one. And drank it over four days in 2017. And loved how it hung on and hung on until it was no more.