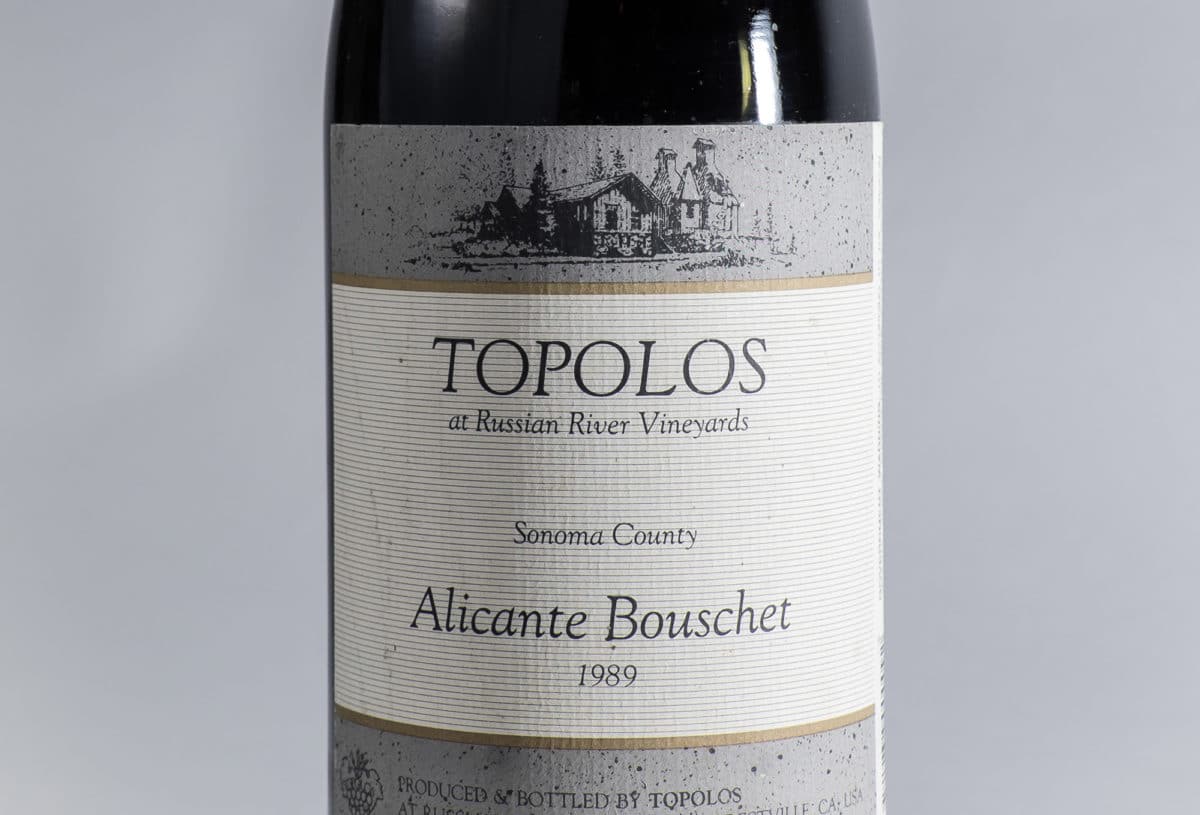

Topolos 1989 Alicante Bouschet

Russian River Valley

One of the first wines I bought in, as it were, bulk, was a wine made solely from the Alicante Bouschet grape. It was produced by Angelo Papagni at his eponymous winery. I believe I initially bought the 1973 vintage, which was his first, and later the more acclaimed (though few wine writers bothered with it) 1975.*

I bought cases of it. Cases and cases. I wish I could remember who had introduced me to the wine. I would, to the extent I am permitted, knight that person.

I suspect it was me, Sir James, and I first tried it most likely because it was beautifully packaged and it cost, at most, $4 a bottle. On its classy (for any wine, not just a $4-at-most wine) label were the words: “Exceptional, full-bodied, deep-red dinner wine, rare in its distinct color and bouquet.”

Well, “rare” is rare—it doesn’t denote quality. And the Alicante Bouschet grape (and therefore wine) has always had a humble, one might in wine-talk say ignoble, reputation. It was bred in 1866 in France by Henri Bouschet, from a cross of Petit Bouschet and Grenache. It was intended as a blending grape, to give more depth of color to wine made from more popular, less florid, grapes.

Which it did. It is that rare red-wine grape that has red flesh. Such a grape is called a teinturier, which means to dye or to stain, though if you ask in France for a teinturier, you’ll likely be sent to a dry-cleaner, because that’s also what dry cleaners are called. (You can see the lexical logic in that if you think about it.)

Most red wines are made from grapes that are red only in their outer skin tissues. Their juice is clear. Thus, the red color of the wine comes from the (macerated) skins.

Not so with our Alicante Bouschet, which indeed produces wines that are “deep-red” but is also thick-skinned and in its prodigious productivity, to quote Jancis Robinson, “almost rude.”

The grape became widely planted in the south of France but even more so in the United States. According to wine writer Talia Baiocchi, by the 1930s Alicante Bouschet, “Prohibition’s Darling Grape,” was the second most planted grape in California, including by Joseph Gallo, Sr., who planted half his vineyards near Modesto to Alicante.

I have no idea precisely when I finished my half-dozen cases of Angelo Papagni’s Alicante Bouschet—sometime in the late 1970s/early 1980s. But I do know that I didn’t taste a wine made from the grape again (my heart belonged to Angelo) until a few weeks ago, when I pulled out of the crawlspace a bottle of 1989 Topolos Alicante Bouschet. Younger than the Papagnis from the 1970s, but still, at nearly 30, old enough and peculiar enough to be an Odd Bottle.

Topolos Winery dates from 1972, when two Topolos brothers purchased 26 acres in Sonoma country and at first planted only Zinfandel. Their grapes were for the most part sold to other wineries, until they bought a neighboring property and in 1978 produced their own Cabernet Sauvignon and went on to make wines from many varietals, including Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and, among reds, Pinot Noir, Merlot, Petite Sirah, Charbono, and our Alicante Bouschet.

A 1996 Topolos Zinfandel was the first Zinfandel ever served at a White House state dinner.

From the beginning, the Topolos family practiced sustainable agricultural practices, and their vineyards were among the earliest in Sonoma officially to be certified organic.

The label on this odd bottle says: “Organically Grown. Dry Farmed. Old Vines.”

Its cork emerged in perfect condition, which, for a wine this old, is unusual (particularly, I must say, for fancy old Bordeaux, whose corks often end up in pathetic shreds).

Poured into our usual large glass, the wine revealed a blood-red core, which one writer has described — for Alicante Bouschet in general — as “gory.”

It faded at the glass’s edge to an amber that matched almost perfectly the colors of the fossilized tree resin that amber is: yellow/orange/brown/red.

Its nose was overwhelmingly of leather — more than I’ve ever smelled in a wine, including those renowned and esteemed for their leather aromas, be it a 35-year-old Barolo or an almost as old Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

It was more saddle leather than briefcase leather, with a greater hint of Italian shoe leather than of British shoe leather, and at the end — not at the tip but at the back of the nose — a whiff of chuto, which is always preferable to the older oto, deerskin. (Hey, I’m joking! Can wine writers and readers not be satisfied simply with “leather?”)

The wine, first sipped, was not exactly the “beefy, brawny, foursquare mouthful” described by Oz Clarke. There was less apparent fruit than acidity, which gave it a bit of a tart and not altogether pleasant bite. This seemed the result not of volatile acidity (acetic acid) but of an actual unresolved edginess in the grape’s assertive and persistent fruit.

But something happened when I actually swallowed it. It had an amazingly long and delectable finish, as if the wine didn’t quite want to leave my tongue and throat, and so it took its own sweet (well, not sweet in the common sense) time leaving my mouth for its trip down my fortunate esophagus.

Yes, Oz Clarke! It was big. It was fruity. It was earthy. It was wonderful.

But it retained that tartness on the tongue. Because of that, I decided it’s not a wine for everyone. Besides, if there is a wine for everyone, I doubt it would be a wine I would want to drink.

Much of, I mean. Those of us who drink wine professionally, whatever that means, must never not try a wine. It would be unethical, foolish, and demeaning to wine itself, which must never be dismissed because of reputation, price, grape variety, label ugliness, foolish name, or popularity. Every wine deserves to be opened and tried, just as does every book. One sip, at least. One sentence read. Then you can toss it away.

I pretty quickly plugged an aerator onto the bottle and poured. The wine made the hissing, gurgling, air-expelling sound as it came out and then bubbled in the glass. It was, in its forced upon diffusion, improved. Slightly.

But the next day, with leftovers (beef), it had lost some of its tartness and none of its fruit.

It got better and better. And then better after that.

Unusually, I did not refrigerate the bottle between tastings. It simply stood there in a cool winter room with the aerator still stuck in its neck (that perfect cork kept as a souvenir — we have perhaps 10,000 such souvenirs).

On the third day, with turkey meatballs, slow-roasted tomatoes, and homemade ricotta, it had, finally, lost most of its tartness and become rounded, fruit-burstingly forward, and still, at 27 years old, promising further decades of bottle age.

Most modest wines should not be aged except for experiments. Some, however, provide as much of a surprise in their old age as an octogenarian turning cartwheels. Which may be a reason to age all modest wines — as in most things in life, the sacrifice of 99 mediocrities is worth a single miracle.

A week old, the last of the wine was drunk with a beef stew. It could have gone on, apparently, well into a second week.

At the final pouring, the bottle produced a healthy dollop of coagulated sediment. A triumphant farewell.

Now some bad news: the Topolos brothers had a falling out and sold the winery in 2008. It is now called Russian River Vineyards. It makes no wines from Alicante Bouschet.

More bad news: Angelo Papagni died in February 2017, at the age of 95 — only some 40 years after I discovered his genius and began to drink his wine.

Some great news: While there is no more Topolos, there is not only still a Papagni Winery, but they are still making Alicante Bouschet. Oz Clarke lists it first among all American bottlings. Jancis Robinson lists no other and tells us, “It was accorded the singular distinction of being house wine at London’s Tate Gallery restaurant.”

More great news: You can still buy the last vintage harvested by Angelo, the 2001, which his son Demetrio describes as having a “brooding intensity” that leads to exactly what we discovered in our 1989 Alicante Bouschet: “an exceptionally long finish.” That wine is priced at $24. Which is almost exactly what $4 in 1973 equals, adjusted for inflation. Let’s all taste it. If not together in fact, then together in spirit. If anything corporeal is spirit as well, it must be wine.

*The very first wine I bought in real quantity was a wine of a generally vastly superior reputation: Chateau Lafite Rothschild. It was from the much maligned 1963 vintage — “1963 Bordeaux wine was bad when it was bottled and time has only made it worse — The Wine Cellar Insider. That’s probably why it was sold to me for $5 a bottle by Bernie Fraden at Quality House in New York City. I bought two cases and have been kicking myself ever since for my short-sightedness. It remains, despite the vintage, one of the finest Bordeaux red wines I’ve had. It was even better than the Angelo Papagni Alicante Bouschet, but what would one expect from a wine that cost a dollar more a bottle? (You can today buy a bottle of the 1963 Lafite for $799 at K&L in California and $2625 at Antik Wein in Berlin.) ![]()