When I took this old bottle out of the crawlspace that is my wine cellar, I was excited (nothing new there) and nervous — something I don’t usually get around wine, which often helps to control my nerves, and that’s without my even drinking it.

I knew that Chalone Chardonnay had had a great reputation and that my bottle had been expensive, that it was the only bottle of it I’d ever owned or would taste, and that it was past the age when any vintage chart or reasonable connoisseur would predict it would have flourished.

Actually, I was more excited than nervous. The worst that could happen was that it would be beyond its time.

The best was that it would be transcendently brilliant. Or at least brilliant relative to its age.

Chalone Vineyard is so high up in Monterey County’s Gavilan Mountains that The New York Times described it as, “virtually inaccessible to any but the people who work there” in what the San Francisco Chronicle says, “looks like the worst place to plant a vineyard.”

It took a Burgundian Frenchman, Charles Tamm, to plant that vineyard, in 1919. He no doubt understood that the ground upon which he walked — in a crunch of limestone and granite and whatever other volcanic rock had been spewed forth 20 million years before from beneath the sea — would be, indeed, what for a time would be the best place to plant a vineyard.

In 1965, a banker turned winemaker, Dick Graff, bought Chalone and, again to quote Meredith May in the SF Chronicle, “turned the Chalone name into a sensation, importing French oak barrels and becoming one of the first to introduce Burgundian winemaking techniques to California.”

The subsequent “sad” history of Chalone may be traced through succeeding editions of Robert Parker’s Wine Buyer’s Guide.

In the first edition (1987), Parker wrote, “The wines here have been distinctive, rich, original expressions of winemaking at its best. The Chardonnays have, in certain vintages, been perhaps the single best white wines produced in California.”

In the second edition (1989): “If life were so simple as to require me to drink only one Chardonnay, then mine would be a Chalone…if one could say there is a Montrachet of California, it has to be the Chardonnays produced at this tiny, isolated property location in the remote Gavilan Mountains.”

In the third and fourth editions, Parker waffled a bit about the ageability of California’s white wines in general but did say, “Chalone makes California’s longest-lived Chardonnays…and in some vintages its most compelling…the greatest new world Chardonnays I have tasted are Chalone’s 1980 and 1981.”

By then (1995), however, Parker was moved to add: “Chalone has never returned to the style of those blockbuster wines.”

And in the seventh edition (2008), he wrote: “One of California’s saddest stories, Chalone provided this critic with some of the greatest Chardonnays I ever tasted in the late 1970s and early 1980s….Dick Graff was killed in a plane crash in 1998, but by that time the quality had already begun to seriously slip…Today, Chalone is part of a larger wine group [Diageo], and the quality is distressingly average…a tragedy given the utterly profound wines that emerged through the decade of the 1970s and early 1980s.”

This opinion and sense of sadness has as recently at October 2015 been echoed by the fine blogger Steve Heimoff: “It has been terribly sad, for a veteran wine guy like me, to witness the trials and tribulations of Chalone Vineyards over the years.”

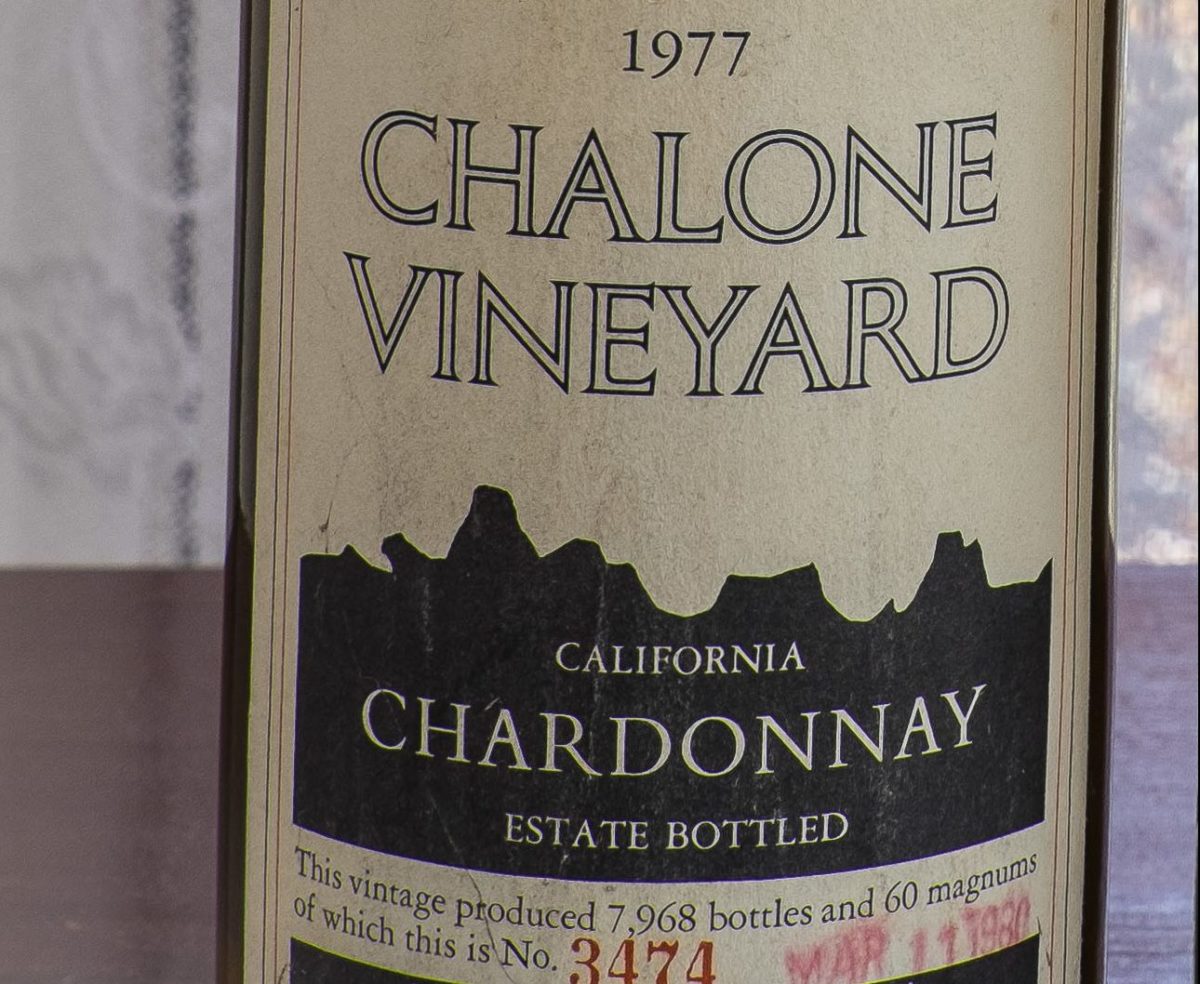

Robert Parker gave no indication that he tasted my particular odd bottle, the 1977 Estate Bottled, the label of which indicates that this bottle is #3474 of 7,968 (664 cases). (Stamped upon it by hand in red is the date of bottling: March 11, 1980.)

It is thus our oldest odd-bottle white wine. I love my wines old, the great ones and sometimes certain modest wines that have hidden away oddly in my crawl-space, developing into unexpected greatness. But there are times when time itself may rob a wine of its beauty and its power, may destroy it.

In the instance of this 1977 Chalone Chardonnay, time had been merciful, perhaps even generous.

The cork emerged wholly intact, except for a small corner wedge that was reluctant to leave its 35-year home.

The wine’s color in the glass was clear, but for only about 15 minutes, when it quickly turned a golden orange, which would seem to indicate that oxygen was an enemy rather than a benefactor. But there was no hint of oxidation, not then, not later.

The aroma was of butterscotch but not so overwhelming as to indicate an over-oaking of the wine in its 2+ years in barrel.

Its mouth-feel was not, however, buttery. It was angular, Chablis-like, and thus might be compared to a much more contemporary Kistler from the Sonoma Mountains, where, indeed, vines are also grown in limestone and volcanic rock.

What was most surprising about this old wine was that it was absurdly, unexpectedly fresh. And any sense of advancing deterioration, which is to be expected in a white wine so old, was immediately obviated by food, in this case a simple shrimp dish. The wine was settled down by food. Its youthfulness was actually accentuated by food.

But, oh, the next day, when it was paired at lunch with an aggressive (capers, garlic) chicken piccata, it was more than up to the task and seemed unchanged in its strength, though it had taken on a smokiness, like a “fumé” wine from the Loire, where the Sauvignon Blanc grapes (normally so unlike Chardonnay) are also grown on limestone soils.

By Day 3, the wine was almost gone — drunk, I mean; not gone over to the dead side. Indeed, it was not only amazingly sprightly but seemed to have improved over Day 2, as unlikely as that may seem. So much did I like the wine on Day 3 that I kept a final taste for Day 4, when it was still going strong (no oxidation) but was going away, out of the bottle, drop by drop, into the glass and off to paradise (mine, as the taster; not its own).

This 1977 Chalone had provided an incredible (in both senses of the word: improbable and magnificent) experience. Almost 40 years old, it was indeed transcendently brilliant — still kicking, still dancing, still elevating an experience of wine into a kind of celebratory joy and a gratitude in its drinker for the fruits of this troubled earth. ![]()