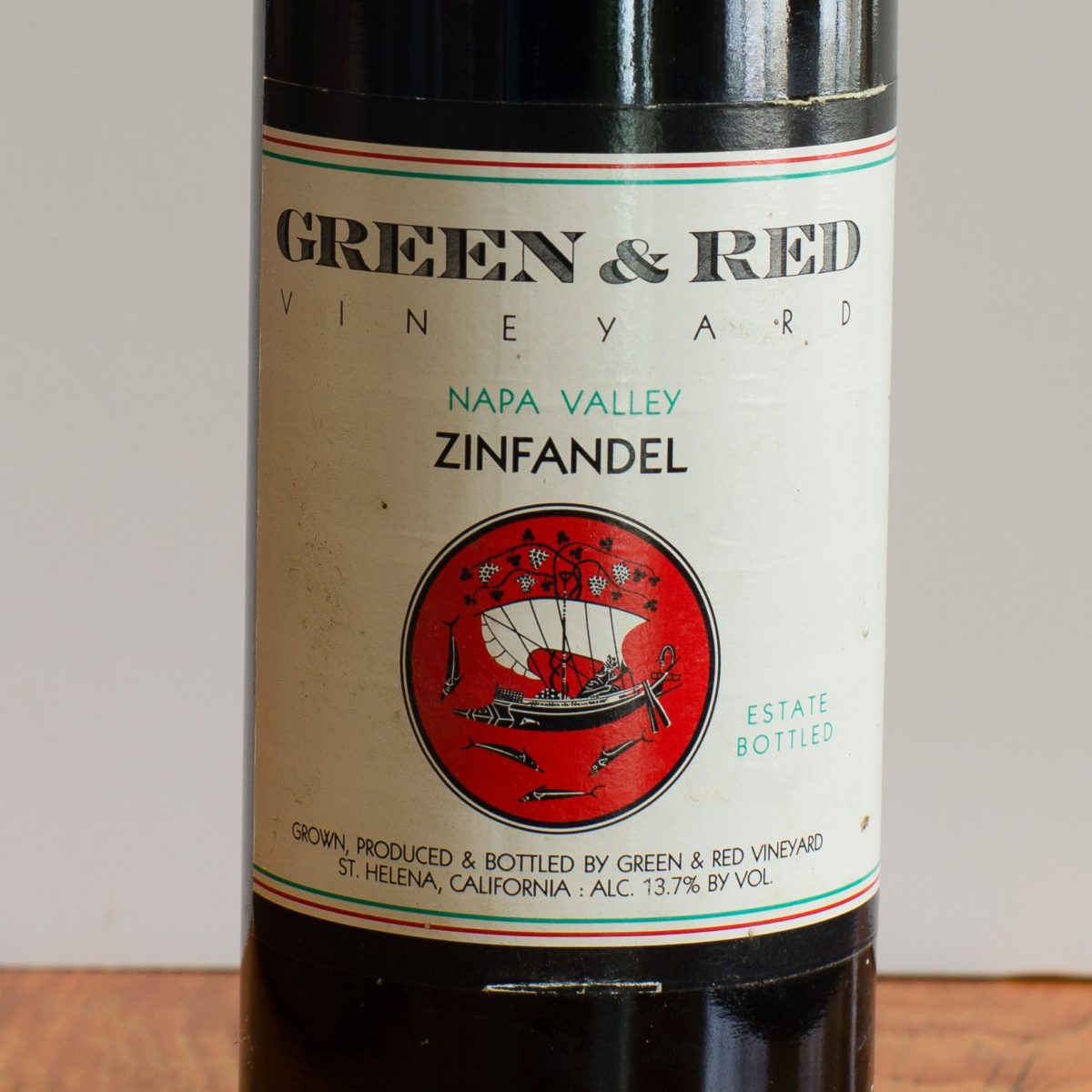

A few years ago I went down to our wine cellar (crawl space, actually) and found a bottle of Green & Red Chiles Canyon Zinfandel, 1977. I took it up to the kitchen and poured a bit into a large Riedel Vinum Syrah/Rhone glass, which is capable of holding almost exactly a full 750 ml bottle of wine.

I swirled the wine, which is always a pleasure to do in a glass so accommodating, stuck in my nose, and took a taste.

With wine still on my lower lip, I rushed to the phone and called my friend Tony.

“Tony, are you busy?”

“Not really. Why?”

“I just opened a bottle of wine and it’s one of the greatest wines I’ve ever tasted. Come over here now. And hurry.”

Tony is Italian and drinks primarily Italian wine. We’ve shared many such wines together, from his cellar and my crawl space: Amarones from the 1960s, Barolos from the 1980s (we’re still waiting for those from the 1970s to come around), Tuscan wines from several decades. A bottle of Mastroberadino’s celebrated 1968 Taurasi Riserva. (We have a 1978 Ludovisi Fiorano rosso in our future.) And as I’ve often said to Tony, if I had to choose one grape, for me it would be Nebbiolo; and one wine, it would be Barolo. I don’t believe Tony and I had ever shared a Zinfandel. Or if we had, there had never been one like this.

Not that I think I would have identified this Green & Red as a Zinfandel had I been served it blind.

I would, as I said that evening, have declared it Italian! (And not of the Primitivo grape from Puglia that is said to be synonymous with the Zinfandel grape but appears to be, in fact, a clone of the Croatian grape Crljenak, as is Zinfandel itself.)

No, this Green & Red didn’t have the common brambly, briary, peppery Zin thing going on. It smelled like an old Barolo, except a bit fresher (which is not necessarily a compliment; and not not a compliment either). It was, at about thirty years from bottling, saturated still with the look of young, purple fruit. It smelled of age when age is perfumed and has thrown off all the poisons of youth and comes out purified and clean. It tasted of the earth, which is often the best thing you can say of a wine.

Tony and I agreed the wine was a fine one.

We’ve shared many such wines together, from his cellar and my crawl space: Amarones from the 1960s, Barolos from the 1980s (we’re still waiting for those from the 1970s to come around), Tuscan wines from several decades. A bottle of Mastroberadino’s celebrated 1968 Taurasi Riserva. (We have a 1978 Ludovisi Fiorano rosso in our future.) And as I’ve often said to Tony, if I had to choose one grape, for me it would be Nebbiolo; and one wine, it would be Barolo. I don’t believe Tony and I had ever shared a Zinfandel. Or if we had, there had never been one like this.

Not that I think I would have identified this Green & Red as a Zinfandel had I been served it blind.

I would, as I said that evening, have declared it Italian! (And not of the Primitivo grape from Puglia that is said to be synonymous with

Green & Red Vineyard is, according to its website, “named for its red iron soils veined with green serpentine.” You can learn a lot more about this Napa Valley winery through doing your own on-line search.

All I’ll repeat here is that 1977 was the first year wine was produced there by that winery, on vines planted by the owner, Jay Hemingway, in 1972; the ground in which he planted them had originally held vineyards beginning in 1890.

I’m pretty sure I had bought this bottle in northern California in 1979-1980. I traveled there often, to visit my young daughter and to work with writers whose books I was editing. And I always bought a few bottles of wine to take back home to New York (in those days, you could take them as carry-on). I shopped in wine stores in Berkeley and occasionally at wineries. If I bought this Green & Red Chiles Canyon Zinfandel when I believe I did, it was in a wine store – Green & Red is to this day not open to visitors and remains the only winery in Chiles Canyon.

I don’t know what I paid for it, but it was not very much, because I never paid very much for a bottle of wine. Today you may buy the latest Green & Red Zinfandels (they make three, from three different vineyards), the Chiles Canyon bottling being the only one blended and the least expensive (and the most prolifically produced: about $23, from about 2500 cases). A special cuvee of it has for years been the house wine at Chez Panisse in Berkeley.

I buy almost no Zinfandels now but still have quite a few from the days when I did buy them. I came to them, as did many wine lovers, through the Zinfandels of Ridge Vineyards, and I still have in my cellar a couple of Ridge Zins from the 1970s, which I hope to drink one day with the same daughter who grew up in Berkeley.

The Zinfandel of which I bought the most was also from 1977, which was, like 2014, a drought year in California (we would collect in buckets the water that dripped off us in the shower and use it to flush toilets). While I had but one bottle of the 1977 Green & Red, I ended up buying at least four cases of the 1977 Mirassou Monterey Country 125 Anniversary Selection Zinfandel, $60 a (wooden) case. There was enough of it left in 1993, when we moved from New York City to New Hampshire, to have served it for our large Thanksgiving dinners for several years after the first, in 1994. At around twenty years old, it was still young and, bottled unfiltered, should have been decanted, but I did not at the time have enough decanters to go around our large Thanksgiving table and so we drank it straight, as it were, and sometimes ended up with a bit of delicious Zinfandel jam on our lips from the bottom of our glasses.

Most people don’t keep Zinfandels long enough to drink them old. Or they drink them young on purpose, because they don’t believe they can age (lack of acidity being the professed reason).

My own feeling about old wines is that I prefer them to young wines. This is a simple enough declaration to make about wines intended to age (like the Italians mentioned above). But, for myself, I am willing to make it about most wines. Or at least most of the wines I have bought over the years and, for one reason or another, have not yet drunk, whether because I deliberately did not open them or because I forgot about them, more likely the former, since I own very few wines I have forgotten about completely.

The main reason I deliberately do not open a particular bottle of wine is that most of the bottles of wine I own are the only bottle of that wine I own, either because I have drunk all the others or, more likely, because I never had more than one bottle to start with. And I always hesitate to open, if there is no one else but my wife and me to drink it, a wine that will disappear from my life once that bottle is gone.

What this means is that I have a cellar full of single bottles of wine, most of which began in that cellar as single bottles of wine and many of which are quite old and unheralded and probably considered a bit peculiar. And what I hope to do in the future, as I did with that bottle of 1977 Green & Red Chiles Canyon Zinfandel, is to open one of those wines every once in a while and to hope, if there’s no one else there tasting it with me, to find it so amazing a wine that I call up a friend to come try it with me, and hurry. Or, at least, to write about it and in that way to share it before it goes the way all wines will eventually, disappearing from the world forever. ![]()

First published April 2014

have declared it Italian! (And not of the Primitivo grape from Puglia that is said to be synonymous with the Zinfandel grape but appears to be, in fact, a clone of the Croatian grape Crljenak, as is Zinfandel itself.)

No, this Green & Red didn’t have the common brambly, briary, peppery Zin thing going on. It smelled like an old Barolo, except a bit fresher (which is not necessarily a compliment; and not not a compliment either). It was, at about thirty years from bottling, saturated still with the look of young, purple fruit. It smelled of age when age is perfumed and has thrown off all the poisons of youth and comes out purified and clean. It tasted of the earth, which is often the best thing you can say of a wine.

Tony and I agreed the wine was a fine one.