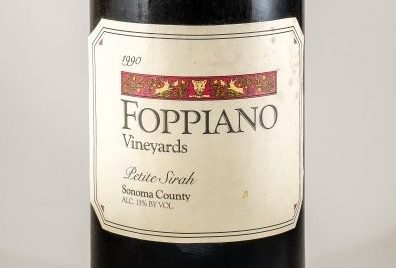

On the back label of this nearly 30-year-old Petite Sirah, we are informed of both history and science:

“Foppiano Vineyard, situated in Sonoma County’s Russian River Valley, has been owned by the Foppiano family since 1896. Our vines, some as old as 55 years, yield superb grapes that produce a smooth-full-flavored spicy wine, which we age for a year in French and American oak….”

Total Acid: 0.68 g/100ml

pH: 3.58

Residual Sugar: 0.2g/100mo (dry)

Petite Sirah is, in general, a simple, relatively inexpensive, increasingly popular wine that provides winerds (i.e., wine nerds) with one of their most common gotchas. Because, they delight in telling the easily confused, the wine has nothing to do with Syrah, which any idiot ought to be able to tell because it’s name is spelled Sirah, not Syrah! (Spell check is silently but persistently admonishing me with a little red whip every time I type the word Sirah).

And, hey, it’s not petite, either, though its grapes are, and that’s where it gets that nom de raisin. It is often, indeed, massive, “notoriously robust and heavy-handed” (Wine Enthusiast); “rigorous though unsubtle,” as Jancis Robinson, sounding like many women describing men, calls it.

So just what grape is it?

It’s Durif.

And what’s Durif?

Durif is a crossing of Peloursin and Syrah.

Wait! So it is a Syrah.

No, it isn’t a Syrah.

Then what is it?

Easy answer: Petite Sirah.

That’s a made-up (and, wine-wise, meaningless) American name for a grape that had first been propagated in France in the 1880s by Dr. François Durif, a grape-growing botanist.

Americans love to give their own name to foreign things. But so do other countries: Burger King is called Hungry Jack’s in Australia. Lays — as in potato chips, not sex talk — are called Chipsy in Egypt.

If you want to drink Durif qua Durif, just go to Australia, where it’s produced under that name by several estates. But it won’t be as good as much of the Petite Sirah produced in the United States. Where, as we now know, it got its name.

And where it made its name. It made that name from the labor and foresight of such early producers as the Foppiano family, which has been growing grapes on its Russian River Valley property since it bought it late in the 19th century. Louis Foppiano, who died in 2012 at the age of 101, first turned his Petite Sirah from a blending grape into a varietal wine in 1967. For him the wine was not heavy-handed; it was “noble.”

I’ve long been intrigued by Petite Sirah, in my early wine-drinking days for its low cost, its inky color (the Foppianos and other makers had blended it with other grapes in order to add color to the resultant wines), and a brash youth that may have matched — actually, overmatched — my own.

I began drinking it in its modest iterations by Parducci and Foppiano. But early on I also had better ones, which I know because I still have a bottle of 1978 Stags’ Leap Petite Sirah and the same of a Ridge York Creek, about which Kelli White wrote recently in Vinous Media, “While the power and dark intensity of Petite Sirah can be often overwhelming in its youth, I have found such wines to be remarkably enjoyable after several decades in the bottle. Inevitably, Petite Sirah’s evolution is a slow one, with the wine stubbornly clinging to its primary elements long after other varieties have traded in their fruit for earth….Ridge’s 1978 Petite Sirah York Creek represents old California at its best…. Drinking Window: 2016 – 2026.” (i.e., until at least 50 years old.)

Okay, so I was probably drinking them too young. I may also have lost my taste for Petite Sirah a bit as I began to be able to afford more subtle red wines, more interesting red wines, more expensive red wines — in particular the red blends of Bordeaux — better red wines.

But I never stopped thinking fondly of Petite Sirah, even as I betrayed it not so much with the rich lady in the penthouse (Bordeaux) as with the brazen beauty in the street (Zinfandel).

And I never stopped saying — long before Petite Sirahs became vaguely popular as American palates were getting trained to tolerate and then demand bigger and bigger (but not necessarily better) red wines — “I’m really quite fond of Petite Sirah.”

And thus it was with a kind of nostalgic hopefulness that I approached this Odd Bottle, the 1990 Foppiano Petite Sirah, which at first held me at arms’ length (speaking almost literally), as its cork utterly disintegrated. And, despite the efforts of the nearby world’s greatest broken-cork extractor (of the human variety and decidedly not me), pieces of the cork ended up floating in the wine at the neck of the bottle.

I didn’t want to decant the wine, in the hope that it would prove worthy of being tested over The Odd Bottle’s customary week or more (always, red or white, refrigerated between tests and warmed up as necessary). Decanted wines tend to die quickly, if rather prettily, swimming lazily over the bottom of their glass caskets.

So I used a funnel with a metal filter and poured a bit of the wine through the filter into a very large glass. Most of the broken pieces of cork drifted, with the wine, into the filter. The pieces left in the bottle would, I figured, make their unwelcome but not significant appearance later. (And they did.)

As for this nearly 30-year-old Petite Sirah, it poured so thickly (colorwise) purple into the glass that it looked like a wine too young to drink. Youth, I thought, having stuck my nose into the glass, might also account for how the wine seemed to want to save its perfume for when we got to know each other better.

“I’ll be back,” I said, the “I” being my nose and the “I said” being my unspoken — because I didn’t want to offend the wine by saying to both it and myself, “Better luck next time” — pledge.

I didn’t want to decant the wine, in the hope that it would prove worthy of being tested over The Odd Bottle’s customary week or more (always, red or white, refrigerated between tests and warmed up as necessary). Decanted wines tend to die quickly, if rather prettily, swimming lazily over the bottom of their glass caskets.

So I used a funnel with a metal filter and poured a bit of the wine through the filter into a very large glass.

Most of the broken pieces of cork drifted, with the wine, into the filter.

The same with my first taste. The wine was substantial in the mouth, weighty and almost commandeering. But, again, it was as withholding as…well, I won’t name any people in my past but I will say, as withholding as most pussy cats meeting you (or me, anyway) for the first time.

But (to continue this possibly silly comparison), like a cat that appears to give the promise that it will eventually fall under the spell of your fingertips behind its ears and the goodwill in your heart, this old, apparently too young Petite Sirah, in the mouth, seemed to be teasing just enough with the warmth of its initial coldness to make me feel that all it really needed was some time in the glass to open up, jump into my lap and make me very happy.

And so it came to be. Or did it?

The food for dinner was, I was told, cured and uncured kielbasa. Wow! Petite Sirah with sausage? Maybe the best of the aggressive, fruity, rustic wines to have with sausage. I could taste them together before I tasted them together. Mind over wine.

What I was not told, before that very old broken cork was removed, was that the sausage was going to be in…choucroute.

Let me say this, and briefly:

Petite Sirah with choucroute? Don’t!

There’s a reason why Alsatians drink their (white) wines with choucroute, with its sauerkraut and apples and caraway seeds: because Alsatian white wines are brilliant with choucroute.

What I rushed to the refrigerator to get, to spell my palate when I wasn’t eating only slices of the bare naked two kinds of sausage, was a St Hallett Australian Barossa blend (Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling) called Poacher’s. I’d had the wine open for several days and hadn’t much cared for it. What I suspect is that this Poacher’s was sitting there in the door of the refrigerator saying (to me, standing outside the refrigerator), “Serve me with choucroute! Stop insulting me and serve me with choucroute!”

So I did. And the vinous part of the dinner was saved. This modest, simple, slightly sweet-seeming wine was delicious with the choucroute. I suspect that was the result of the Riesling in the blend. True, the blend was only 8 percent Riesling. But the wine, which had cried out in such desperation from the door of the refrigerator, redeemed itself (and, for me, the entire Barossa Valley) by knowing its place in the world (replacing a Petite Sirah to go with sauerkraut and apples and caraway seeds).

At dinner the next day — Guinness beef stew with Irish soda bread — the Petite Sirah was a bit more forthcoming and was, in any case, a suitable companion to this late-winter stew (eaten mostly with a spoon).

Where it was even better was with that thick, dense, wheat flour and oatmeal bread, which, held in one’s mouth, could become saturated with the wine, and then the two of them — swimming around under one’s palate and over one’s tongue — could be swallowed in a kind of hallowing of the eternal symbol of heaven on earth: bread and wine (pane e vino).

On Day 3 the wine rested.

On Day 4, drunk again with Guinness beef stew, the wine had me wondering, “When are you going to die?”

And then, unkindly: “When are you going to live?”

Growing tired of waiting for either, or both, I opened a very recently acquired California wine called Mega Petite: “This Petite ain’t Petite” (on the front label). Oh, please! Spare us such ad copy on wine labels. Not to mention wines with names, let alone big little paradoxical names, like Mega Petite.

Its back label, at least, first thing, lists the three grapes in this wine: Petite Sirah (which is to be expected from the wine’s given name), Malbec, and, of all things, Teroldego.

The winery goes on to call this bottle the “epic debut” of Mega Petite, “this muscular little fellow.”

The only thing that saves Campbell & McGill, the winery (Acampo, CA), from having to apologize to the entire state of California is that the wine is pretty good. I opened it to see how a supposed Petite Sirah 24 years younger than our confusing Odd Bottle might compare. I’d grown tired of trying to coax more than a kind of muscular tenacity out of my Foppiano.

Well, the Mega Petite made me appreciate my Foppiano, and my Foppiano made me grateful to have the unabashedly forward, almost springy, Mega Petite. It was no contest. By which I mean…there was no contest. The two wines could peacefully coexist, so long as they weren’t living together in Choucrouteville.

On the 5th day, the Foppiano was its best yet, with rotisserie chicken and a slice of spicy-sausage pizza. This was its first appearance at a lunch. Petite Sirah had always seemed to me a dinner-time wine, heavy and deep and customarily alcoholic. But perhaps the freshness of my palate at a relatively early time of day brought me to conclude that the wine was at its “best yet,” by which I meant fresher (yes, on day 5), fruity (finally!), and opening up (finally!!).

At dinner on Day 6, yet again with leftover stew, there was no diminution of the power of the wine but no increase in its distinction. It had proved to be a drinkable California red wine that stood out vastly more for its age than for its beauty.

What this almost-week* with the 1990 Foppiano Petite Sirah shows (not proves; in the world of wine, there is rarely proof of anything) is that there are some wines that, however unexpectedly, appear to be immortal. But, as with human beings, immortality (longlivedness) is no guarantee of quality.

As I said, Petite Sirah is becoming more popular. It even has a fan club. Foppiano, as is reported in the San Francisco Chronicle, spearheaded the creation of this “organization dedicated to the Petite Sirah’s advancement, cheekily named P.S. I Love You.”

*I decided not to test this wine further, with about 118 ml (4 ounces) left in the bottle after nearly a week. Will I drink this wine? Of course. Will it have improved? No. Will it have declined? That will be my and this (modest but immodest) wine’s secret. ![]()