Wine writer Oz Clarke in his book Grapes & Wines devotes a meager two pages to Pinot Blanc (eight to Chenin Blanc, ten to Pinot Noir). To add editorial insult to, if I may, volumic injury, he begins that brief chapter with these words: “I can’t think of a single region in the world where Pinot Blanc is regarded as a star grape.”

It is, nonetheless, what Jancis Robinson calls a “true Pinot,” in that it’s descended from Pinot Noir and is related to Pinot Gris (which itself may be a mutation of Pinot Noir). If that’s confusing, consider that while you may know the grape in its Pinot Bianco iteration from Italy, Robinson assigns it at least 16 other names in other countries.

I’ve drunk very few Pinot Blancs, probably because those I’ve tried, especially from Alsace (where the wines are also called Pinot Blanc), never came close to providing the pleasure of the first Pinot Blanc I drank, which was, as is this Odd Bottle, an American wine, from Chalone.

That was many years ago, perhaps 1983, and I don’t recall what vintage it was, probably from the 1970s, but I do remember exclaiming over it to my wife, then saying, “Try this wine,” but pouring her, with a terrible selfishness known to wine lovers, only a tiny taste. (Wine lovers are vinously parsimonious in this fashion only until the person thus victimized smiles, or gushes, in agreement and in visible understanding of one’s own enthusiasm; then the pour becomes generous and the pleasure genuinely and equitably shared.)

When that rare bottle was gone, I didn’t think I could find or afford another. I planted the wine in my mind, as we all sometimes do with something we know we’re giving up at the same time that we attempt to keep it forever, if only as a memory.

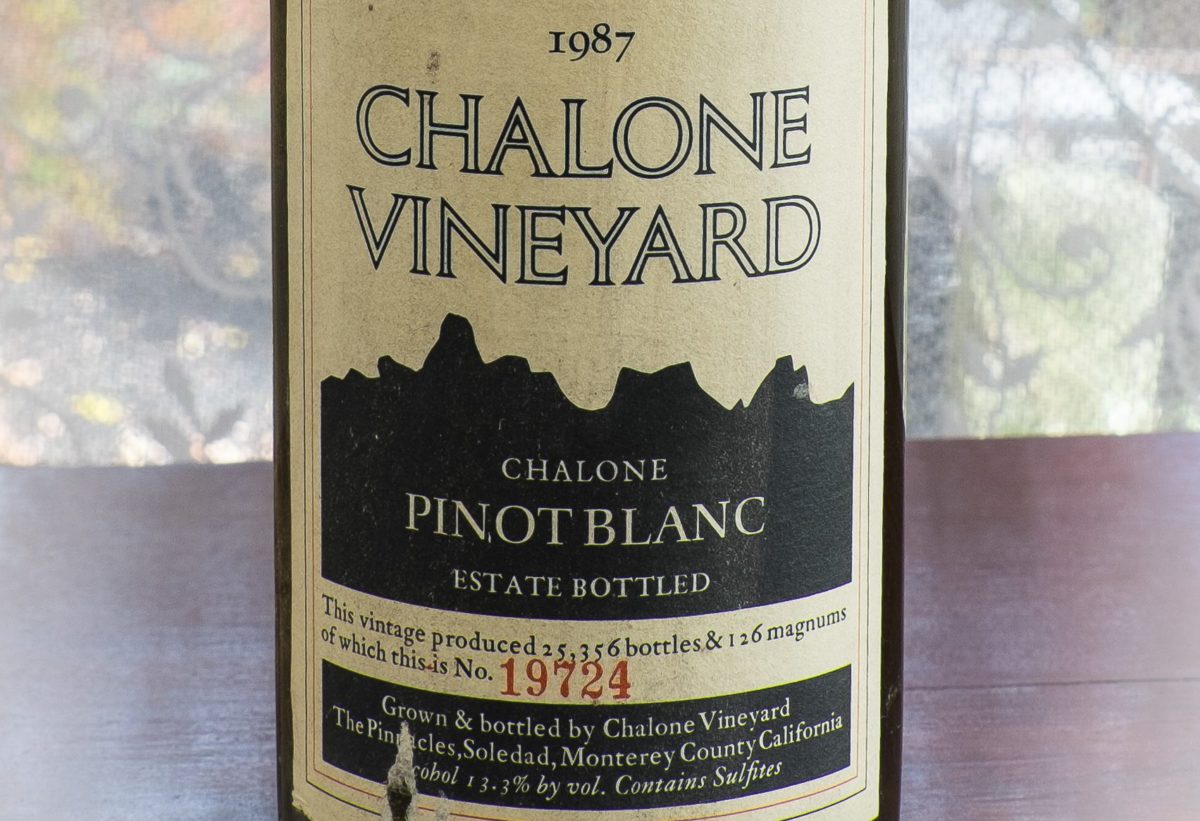

So imagine my surprise when one day my wife presented me with a bottle of Chalone Pinot Blanc, vintage 1987.

“Where did you find this?” I asked.

She must have feared I would go out and spend a month’s rent on a case of it, thus diminishing the luxury and personal nature of this special gift. She said only, “It was very hard to find.”

Even I, in my lust for more of the wine, knew enough to be silent and accept that bottle for what it was to become: an Odd Bottle nearly 30 years later.

No, not really. I had no plans then to write about wine and no plans to keep that bottle for almost three decades.

But I did. Why? Not for a wine column I never imagined I would write. I kept it because it had become so special as one of the first gifts of my young marriage and a wine I genuinely welcomed (wine lovers are notoriously difficult to buy the right wines for) that I kept it as a kind of talisman, a magic bottle that held and signified the magic of my marriage.

Well, that was this very bottle. The one pictured here: “Grown & bottled by Chalone Vineyard. The Pinnacles, Soledad, Monterey County California.”

What about what was inside the bottle? What about the wine? Would it prove to be as alive and satisfying as the marriage of thirty years?

Before we answer that metaphoric question, it will help to know that Chalone vineyard, while located toward the foot of the Pinnacles National Park extinct volcano, consists of soil not of volcanic basalt (aka Jory, so critical these days to the success of wines from the Dundee Hills of Oregon’s Willamette Valley) but of limestone and granite.

Guess what? Chalone was founded toward the end of the 19th century by a Frenchman who believed he could make wines there that would be Burgundian in style. Why? Because the soil in Burgundy is also composed of limestone and granite.

Chalone is most famous for its Chardonnays, as is Burgundy. But Chardonnay is also a Pinot grape. (When I first started drinking wine, one would always ask for Pinot Chardonnay, as Chardonnay was then known.) And Pinot Blanc is grown in Burgundy and at one time composed 20 percent of the most famous red wine in Burgundy, Domaine Romanée Conti. Today DRC is 100 percent Pinot Noir. But there is a small amount of Pinot Blanc blended into some white Burgundies, for example Vougeot 1er Cru “Le Clos Blanc de Vougeot.”

But wait. Pinot Chardonnay and Pinot Blanc in the same breath? In the same paragraph?

Jancis Robinson writes of how, in blind tastings in California, Pinot Blancs have performed exceptionally well “against” Chardonnays.

I’m guessing that at least one of them must have been the Pinot Blanc from Chalone. Of Chalone’s Chardonnays, Robert Parker wrote in the 1987 edition of Robert Parker’s Wine Buyer’s Guide, “The [Chalone] Chardonnays have, in certain vintages, been perhaps the single best white wines produced in California.”

Of Chalone’s Pinot Blancs, Parker writes, in the same volume, with the same superlative, “Chalone makes the best Pinot Blanc in California.”

Why might this be so, aside from all-important matters of terroir? Because, as Jancis Robinson writes, “The lofty Chalone Vineyards have done Pinot Blanc one of the greatest favours by treating it as a very serious varietal wine…they have accorded Pinot Blanc the compliment of oak-aging, an unheard-of luxury elsewhere in the world.”

Parker writes that most Pinot Blancs are uncomplicated wines that don’t age well and should be consumed by the vintage’s third year (I don’t disagree) “…the only exception being those made in a full-bodied, structured style such as Chalone.” (I agree!).

He says, “The aging potential of Chalone’s Pinot Blanc is amazing” and that they drink well for 6 to 10 years.

You want amazing? Try a Chalone Pinot Blanc after 30 years.

Our Odd Bottle, this 1987 Chalone Pinot Blanc, opened to our new world when its cork emerged half-saturated but wholly intact except for a broken-off wedge at its bottom end.

The wine was poured, without even a speck of cork, into a medium-sized Chardonnay glass.

In the glass, the wine showed the elusive color of old white wine (or young Sauternes). You don’t know, when you stick your nose into a glass of almost golden, sometimes also almost brownish, dry wine, if you’re going to smell wine (i.e., fruit), flowers, a breeze of spice, vinegar, rot, or the death of a liquid (which can smell of nothing and of something unimaginably awful at the same time).

The wine was arrogantly withholding. It seemed to be saying, “Get your nose out of the glass and have a taste.”

I don’t like to be ordered around by a wine, and I was worried about this treasured bottle (treasured because of its origin—and I don’t mean the Chalone-located Gavilan Mountains but the generosity of my young wife).

But then one taste, one small taste, dispelled all my doubts. The wine was big in my mouth, pushy, almost, like a guest who feels both undervalued and confident.

I swallowed and stuck my nose back into the glass. Up came, now, a seductive aroma, spicy and floral. I wondered if its vapid first impression was the result of its needing a bit of time (i.e., oxygen) in order to blossom or that I had somehow been holding my nose out of fear, the way I used to close my eyes when swinging at a baseball, rendering failure out of fear of failure.

Jancis Robinson writes that Pinot Blanc has “well delineated fruit flavours.” But I noticed that she doesn’t mention a single one of those fruit flavors. I am not a particularly gifted or even interested delineator of fruit flavors. In the case of our 1987 Chalone Pinot Blanc, I could detect no particular flavors. (Those most commonly associated with Pinot Blanc in general are pear, apple, and the indistinct “citrus.”) The wine’s welcome, impressive amplitude in my mouth, mentioned above, was most likely the result of its having been aged in oak.

We drank the wine at its inaugural meal with sushi-grade salmon, grilled to be rare enough to be room temperature melding into air temperature (it was a chilly night). More challenging to so old a Pinot Blanc was an accompanying baked clam with a spicy stuffing and steamed broccoli with a chili aioli dipping sauce. To all these foods, the Chalone presented a united front, somehow adjusting to the milder salmon, gathering strength then against the peppers.

On the second day, the wine gained a richness even as it lost what little bit of oxidized funkiness it had begun to show toward the end of the long, first dinner of its condemned life.

And it needed to be rich, because it was tested against even more spice in what was called spicy basil chicken, double-cooked pork, and, in particular, a very spicy Szechuan tofu.

Who would have thought a Pinot Blanc would stand up to these spices? Might it be only this Pinot Blanc? But at 30 years of age?

It didn’t triumph over the spicy Chinese food. It joined it in celebration of a victory over (somewhat demeaning) expectations.

Day 3: accompanying chicken grilled with olive oil, lemon, and sun-dried tomatoes.

Day 4: with Thai pork meatballs (not spicy) and Cornish hens with cornbread and sherry stuffing. Oh, did the by-now slightly oxidized Pinot Blanc meld with the deliberately oxidized sherry!

Day 5: the small, remaining bit of wine was allowed a day off.

Day 6: finally, leftovers! The chicken from Day 3.

After almost a week, the wine was nearly as fresh as the day it had been opened. A 30-year-old wine from a somewhat ordinary grape, made by Chalone into an extraordinary wine.

At the end of his short chapter about Pinot Blanc, Oz Clarke writes, “It’s difficult to know how good Pinot Blanc could be.”

This Chalone, Oz, was probably as good as Pinot Blanc could be. It’s not a region, but, as Chalone describes itself, “perched in the remote Gavilan Mountain Range, 1,800 feet above California’s Salinas Valley,” this is where Pinot Blanc became a star. ![]()

First published April 2016