Here are six odd wine grapes coming to you from The Odd Bottle: Airen, Garnacha tinta, Rkatsiteli, Sultaniye, Trebbiano Toscana, Manzuelo.

Here are six seemingly less odd wine grapes: Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Airen, Tempranillo, Chardonnay, Syrah.

In each case, the grapes are listed in a certain order. And what order might those be?

The first are the six most planted varieties in the world, in 1990.

The second are the six most planted varieties in the world, 20 years later.

Aside from the fact that they share only Airen (a Spanish white-wine grape used mostly in brandy), these little lists display a shift in wine growing and, consequently, in wine consumption that indicates…well, I was going to say greater sophistication among wine drinkers, but since that might get me accused of elitism (though I would love to deserve that honorific), I will say only that the shift is toward the making and enjoying of much better wines.

Merlot remains today, in the United States, the second most popular red grape/wine. It’s a more gentle, approachable, food-pairable wine than Cabernet Sauvignon. It also tends to cost less.

In France, where the grape was first made into wine in the late eighteenth century, it was and is best known as a blending grape that was used with Cabernet Sauvignon in Bordeaux to produce what what many consider the greatest red wines in the world. (Certainly the greatest blended wines. Adherents of Pinot Noir and Nebbiolo may prefer the wines made from those grapes, but they are not blended.)

There is one exceptional wine in Bordeaux that has (since 2010) been made entirely from Merlot. It’s considered by many the finest French red wine. It is the most expensive red Bordeaux (from about $3200 to $60,000 a bottle), even if it ranks only #26 on Wine-Searcher’s latest (May 2018) list of the world’s 50 most expensive wines.

In the United States, Merlot is also used as a blending wine, usually with Cabernet Sauvignon, to produce a Bordeaux-style blend that is sometimes labeled Meritage (rhymes with heritage).

But it’s in the United States, much more than in France, that Merlot is presented, and proudly, as the grape that makes up 100 percent (or nearly) of the wine that bears its name.

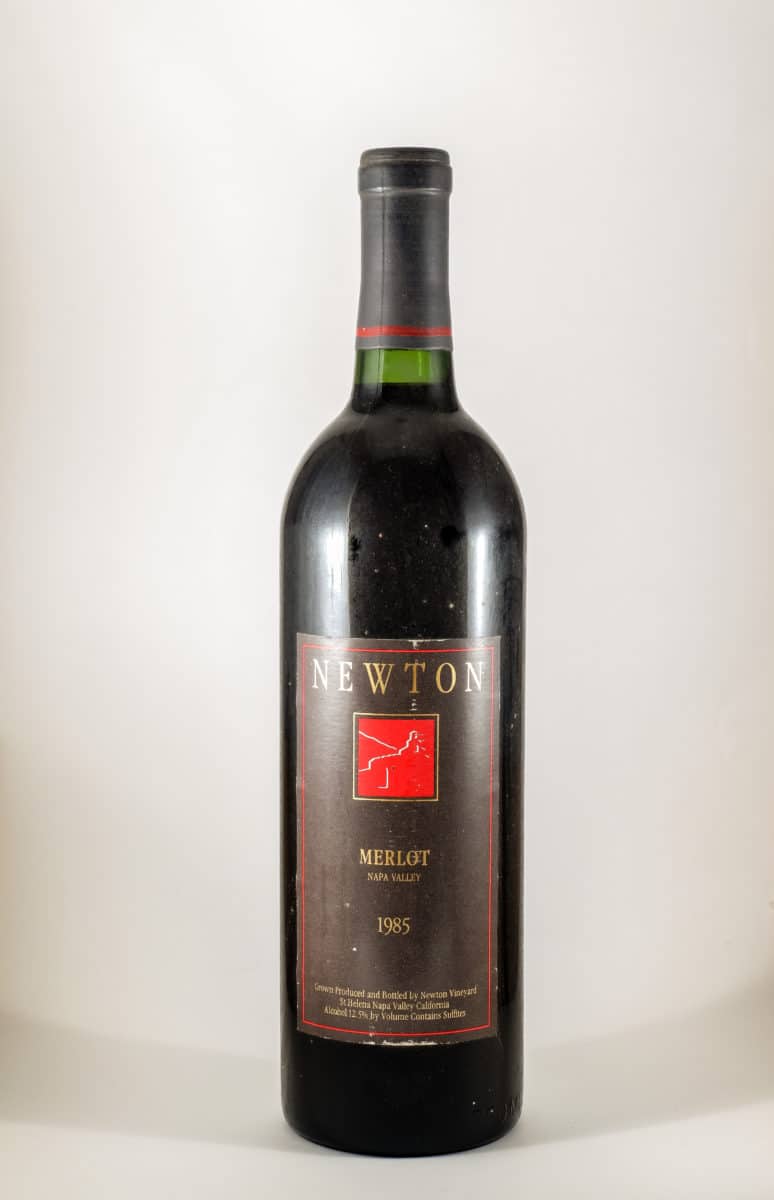

This 1985 Newton Merlot, for example (which may have been blended with a tiny bit of Petit Verdot).

I’ve owned this bottle for perhaps 30 years. I became something of a (very minor) collector of Newton wines (but only the 1984 and 1985 vintages) after I’d made one of the worst faux pas of my life (speaking wine-wise; in matters of love and tennis, I’ve made many more).

I was attending an American Booksellers Association Convention in San Francisco. I’d made friends with a young British editor. One day he told me that he was organizing a trip to visit his father’s winery in Napa.

“What’s the name of the winery?” I asked.

“Newton Vineyard.”

My friend’s name was Nigel Newton. I’d never heard of Newton Vineyard, and I thought, “Oh, no, Nigel’s dad must be growing grapes in his backyard and making wine in his basement. Not only that, but he’s British.”

“No, thanks,” I said. “I’m so busy.”

Yes, I was busy. We all are on the floor of book conventions. I was also an arrogant, ignorant fool.

I have since learned that there is no wine one should resist taking at least one taste of, no matter how unknown it is; how known (popular) it is; how inexpensive it is; how expensive it is; how foolish its name or vulgar its label.

Only later did I learn that Nigel’s father was Peter Newton, who in 1964 had founded Sterling Vineyards (of which I’d decidedly heard — it was one of the most famous Napa Valley wineries), sold it to Coca Cola, and then founded Newton Vineyard, which I could have visited in its infancy* if I hadn’t been such an ignorant snob.

Oh, Nigel Newton also founded something. A British publishing house called Bloomsbury. Ten years later, in 1996, Nigel handed his young daughter the first chapter of a novel that had been rejected by a dozen other publishers. Alice Newton read it and said, in essence, I want to see more!

And so was born the public existence of the first Harry Potter book; the career of Joanne (no middle name) Rowling; and the extraordinary success of Bloomsbury and of my old friend Nigel Newton.

How could I not, then, think of Nigel as I opened my 1985 Newton Vineyard Merlot, “Grown and Bottled by Newton Vineyard, St. Helena, Napa Valley, California. Alcohol 12.5%?”

There was no government warning — these were not forced on winemakers until 1988. I’ve always been partial to wines with no such label. When friends serve from a bottle with no such label, and it is post-1988, I say, “You bought this overseas.” “How do you know?” they sometimes ask. “No warning label!” I exult.

There was also no back label. I suspect there had been one and it had fallen off and away in the over thirty years since this wine had been bottled and I had bought it and stored it away, just waiting for an Odd Bottle moment.

The cork was a disaster. Should I have called Nigel to tell him? No, despite the fact that the very long worm in my corkscrew had left the cork broken in two, with half coming out on the worm and with it many fragments of cork; the other half looking ominously threatening (to dive into the wine, halfway down the neck).

Rigorous, delicate digging with an even longer worm — and not by impatient me but by the world’s best broken-cork extractor (a designation bestowed by several great collectors of wine) — brought forth the decayed rest of the cork, seemingly intact.

But when I then poured the wine into a very large glass, tiny pieces of cork were swimming around in it, looking like miniature tadpoles (to the extent that I actually, truthfully, did wonder if they were alive).

I didn’t decant the wine (because I always test these Odd Bottle wines over a number of days, and decanting seriously reduces their life expectancy). I hoped I had the majority of the tadpoles. (And I did.)

The long-delayed opening of the bottle did release fragrance into the kitchen. That fragrance was only a precursor of what the nose experienced when lowered into the glass: a delight of fruit and smoke, a sense of youth (fresh) and age (fresher…well, fresher in the sense of surviving in bloom).

I thought, “This smells like an old Bordeaux.” And if I were truly bragging, I would write here, “This smells like an old Right-Bank Bordeaux.” (It is from vineyards on the right bank of Bordeaux’s Gironde River that Merlot is predominant.)

The colors of the wine were those of classic aging, a center off-red to yellow-gold to almost pale wateriness at the very edges.

The first taste: an immediate leap of tart, satisfying fruit, mouthy, gum-embracing, long-finishing, superlative-thought inducing, exclamation producing (as in, to my resident cork extractor, “Put down your corkscrew [well, in her case, by now, meat-turning tongs] and try this wine!”)

She did. She exclaimed (how could she other? I mean, exclaimed positively). Then she went back to her tongs and with them seized upon what had been paired, hopefully (if I may use that word correctly), with this Odd Bottle: grilled lamb chops, seasoned with nothing but salt, pepper, and garlic.

If I tell you how good that was, you might kidnap me and eat me.

The next day we had leftovers of the same food. The Newton Merlot was a bit less tart and thus even more Bordeaux-like.

On Day 3 it was served with split chicken breasts (grilled) in a thick gravy (tinged with red wine, but not this red wine). The wine had further softened, which suited the chicken.

We had a small bit of the wine for dinner on the fourth day, with some take-in Chinese food. It was good with the beef with broccoli. It was good with the double-cooked pork. It was not good with the extra-spicy ma-po tofu.

On the 7th day the wine died. Actually, it was on the 5th day, and it was not a failing of biblical proportions. It was, however, at the altar of a truly American meal — as suited this truly American wine (if one may permit it a French grape): burgers and fries. The fruit essence of the wine was gone. But, then, so was all the wine.

Everything dies. But a great wine, however tired it may have become fighting its lifelong battle with the air itself, dies greatly. As it had lived.

*Some years later I visited Newton Vineyard alongside Bob Thompson, a wine writer I was publishing, a brilliant man who has been called “the sage of St. Helena” and “the dean of California wine writers.” It was one of the perks of my job that I got to travel and taste with such a person.

One day Bob took me to Newton Vineyard, and we had an exhaustive tour of a winery described by Robert Parker as “one of the most gorgeous mountain estates in California.” I was especially impressed by Newton’s famed mountain cave, in which its barrels of wine are aged and from which we emerged nearly two hours after our tour had begun, impressed, tired, and thirsty.

And we were sent on our way. No wine. Not a drop. I was new at this, and a guest of my writer, so I didn’t say anything.

Bob Thompson wasn’t new at this, but he was polite and diplomatic, so he said nothing until we were on our way down the mountain.

“That was very peculiar,” he said.

And off we went to lunch. ![]()