Several months ago I ordered a wine in a restaurant, and the sommelier looked down at me and shook her head and said, “You won’t like this wine.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Most people don’t like this wine.”

I didn’t ask why, then, was the wine on the wine list? It was there because I was on a cruise ship, and this wine was among those offered in what they call a “wine package,” a group of wines you purchase in advance and from which you may choose any. This objectionable wine would remain on the list until people like me stopped ordering it.

And I did order it.

What wine writer in his or her right mind would not order a wine that “most people” don’t like?

People often don’t like the wines we like. Wine is not a popularity contest. Wine tasting and studying is a search for what is best. And what is best is, in wine as in art and literature, not what most people “like.”

That wine was a 2012 Elsa Bianchi Torrontés, from grapes grown in the Dona Elsa vineyard at Bodegas Bianchi, one of Argentina’s oldest wineries.

Torrontés is a relatively simple white wine made from the grape of the same name, solely in Argentina. It’s meant to be drunk young (it is not high in acidity), and a 2012 Torrontés in late 2017 was not a young wine.

But it turned out to be a wonderful wine.

I could tell immediately why the sommelier recommended against it. It was slightly oxidized.

For me, oxidation has become something of a mystery. In testing wines for The Odd Bottle, I drink them over a period of at least 3 days and sometimes over more than a week. And almost all of them are “old” wines, in that they are past what is generally considered to be their peak (never mind that they tend to be decades in actual age from harvest). With one exception (a Pinot Noir from The Finger Lakes), no old wine I’ve opened has been “too old” to drink. (Not that any wine may truly be, at least to taste. Is any person too old to dance?)

The moment a bottle of wine is opened, it is exposed to more oxygen than it had been when corked. And yet, I’ve noticed, in more cases than not, that a wine that seemed oxidized on Day 1 may lose at least some of its sense of being oxidized on Day 3. I have no explanation for this. It’s as if the very thing that threatens a wine (oxygen) also succors it. (This is a matter not of science but of sensuousness.)

I liked that Torrontés so much that I told the sommelier I might order it again some evening. She smiled and shook her head, as if she couldn’t believe her luck (“Maybe I can get rid of that awful wine”) or she couldn’t believe I was such a deluded winomaniac.

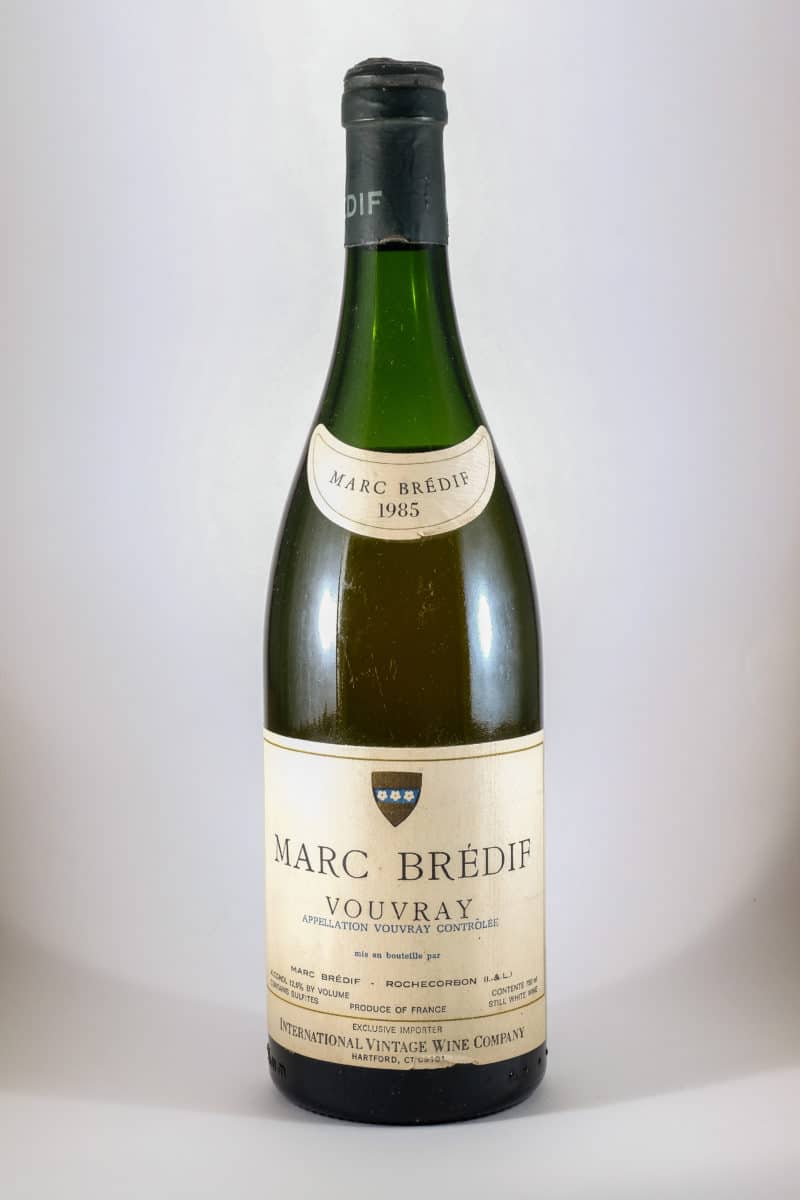

I relate that story of the oxidized Torrontés because I had a similar, if homebound and extended, experience with our Odd Bottle here, the much older and much more seriously rendered 1985 Vouvray from Marc Brédif.

All Vouvrays are made from Chenin Blanc, a substantially more distinguished grape than Torrontés, though wine writer Matt Kramer does call it (in extolling its virtues) “the Great Forgotten Grape.”

Chenin Blanc finds its greatest expression in the Loire Valley of France. (South Africa may be catching up.) It’s been grown there for almost fifteen centuries. I’ve known it — lucky me — primarily in its incarnation in Savennières, in particular in the Joly family Clos de la Coulée de Serrant, which is considered one of the three greatest white wines in the world.

Savennières, once known for sweet wines, is now a dry wine. It is capable of great longevity — the most for any dry white wine, in my experience. We are still drinking Coulée de Serrant from 1980, 1981, 1983, and 1984, none of which is considered any more than a “good” vintage. (Alas, I’ve never had even a taste from what has been called the “exceptional” 1982 vintage.)

Vouvray is made dry, tendre (off-dry) semi-dry, and sweet (Moelleux). Most dry Vouvrays have the word “sec” on the label. Our Marc Brédif is presumably tendre, more dry than sweet.

Vouvray is also made into sparkling wines, dry and sweet. Here we’re concerned with Vouvray as a still wine.

Both Savennières and Vouvray are on the right bank of the Loire. The former is part of the Anjou Saumur, the latter of Touraine.

Maison Brédif was founded in 1893 and has been said to be “one of the best known and most respected houses not only in the region but also in the world.” Wine writer Dan Murphy writes that the domaine is “renowned for the longevity and quality of [its] Vouvray.”

Marc Brédif was purchased in 1980 by Ladoucette, whose renowned Loire Valley Pouilly-Fumé was the first Sauvignon Blanc wine I ever experienced, in the late 1960s. Might as well start near the top (thanks to my generous, cagey wine merchant).

Vouvray is made dry, tendre (off-dry) semi-dry, and sweet (Moelleux). Most dry Vouvrays have the word “sec” on the label. Our Marc Brédif is presumably tendre, more dry than sweet.

Vouvray is also made into sparkling wines, dry and sweet. Here we’re concerned with Vouvray as a still wine.

Both Savennières and Vouvray are on the right bank of the Loire. The former is part of the Anjou Saumur, the latter of Touraine.

Maison Brédif was founded in 1893 and has been said to be “one of the best known and most respected houses not only in the region but also in the world.” Wine writer Dan Murphy writes that the domaine is “renowned for the longevity and quality of [its] Vouvray.”

Marc Brédif was purchased in 1980 by Ladoucette, whose renowned Loire Valley Pouilly-Fumé was the first Sauvignon Blanc wine I ever experienced, in the late 1960s. Might as well start near the top (thanks to my generous, cagey wine merchant).

I’ve owned this bottle of 1985 Marc Brédif Vouvray for at least 20 years. I’ve often told myself to buy more Vouvray, because it is one of the finest white wines in the world and, for a fine wine, perhaps the greatest bargain. But I haven’t. This is one of the only bottles, from any winery, that I have. All the more reason for us to try it as an Odd Bottle.

I chose to open it to accompany a dinner of smoked ham. I thought the smokiness of the meat would be complemented by the expected rich, structured, quinciness of the wine. Great expectations. (Good title for a wine book. And, yes, I’m aware there’s a wine book called Grape Expectations.)

Uh oh. The Vouvray’s cork, from a mere touch of the opener’s worm, slipped right down into the wine. Since there was no penetration of the cork, it was wholly intact, as it floated there. This was a good thing, because I didn’t want to decant this wine, and I would have had to if the cork had crumbled into the liquid. (In contrast, it is suggested by the owners of Coulée de Serrant that their wine be decanted for…two entire days!)

When I poured the wine, there was absolutely no cork detritus. I’d been correct not to decant it, because, as I immediately discovered, the last thing this wine needed (or so I thought) was more oxygen.

It was oxidized on the nose. The oxygen dominated whatever aromas of pear and quince might be expected.

In taste, the wine was seemingly half oxygenated liquid and half fruit. Big fruit. But that oxygen…

I remembered the sommelier on the ship and imagined serving this wine to someone and saying, “You won’t like this wine.”

But I did. In decidedly small mouth-rinsings and then swallows, yes, I liked it. Not enough not to be disappointed. I had wanted it to explode like a Savennières. It didn’t. But it held up to the ham and it held up to my somewhat insecure — on the wine’s behalf — expectations.

But what were my expectations? Actually, I had none. I open these old bottles with the minor sense of dread that wine people do, fearful mostly that they’ve kept a wine too long so that when they smell and taste it, they will find reason for blame — of themselves, mostly, not of the wine.

So it’s with great joy that a wine opened with dread is experienced as a wine almost knowingly (for wines are living things) surrendering its pleasures. It’s a wonder some of us don’t shatter our wine glasses with our immediate beaming smiles of relief and surprise.

Those who turn away from a compromised (as distinguished from flawed) wine may never come to know what they’re missing. Perhaps they (we) expect perfection in our fine wines. Aside from the fact that there may be no such thing (in so subjective an experience as wine-drinking), what such an expectation can produce is an inability to search beneath, as it were, the surface of wine for the goodness (and we’re not talking health here).

Further tasting of a disappointing wine may bring you to the heart of the wine, which is where the fruit lives, and perhaps the necessary acidity, and the minerality — the taste of the wine beneath, and thus also above, its apparent deficiencies.

This is not unlike a person of whom the first impression is one of disappointment. Not unlike coming to love the inner person only after the experience of the initially disheartening outer person.

Thus did this apparently compromised wine survive (i.e., not being poured out) until the next day, at lunch, a challenging roast chicken with Sriracha and roasted garlic barbecue sauce, to whose spice and heat the Vouvray held up beautifully. It occurred to me then (and I made written note of this) that spice and heat might mitigate the oxidation, perhaps by masking it or, better yet, by accommodating it, by folding it into the taste experience.

As I said above, this may defy the science of the matter. And in these days, when science is being defied by those at the very top echelons of government (and at the very lowest of civilization), far be it from me to defy the very science they defy.

The third day, the wine was absolutely superb with sushi-grade marinated salmon with a mustard-dill sauce.

The sixth day, at dinner, the little remaining, almost week-opened wine was at its best yet. All oxidation was gone from the nose (where it had previously dominated). It now came forth on the palate and was welcome there as it was drunk with a challenging dish of bourbon-marinated roast tenderloin of pork. The challenge came in a very assertive white sauce made with a tablespoon of hot Coleman’s mustard. This is a dish I would normally pair with a Gewürztraminer or a Riesling Spätlese (i.e., intensely fruity or more than slightly sweet). But the old Vouvray was perfect with it.

The woman who created this recipe had written across the top of it: “Not for the Common People.”

So with this 1985 Marc Brédif Vouvray. You won’t like it. You may love it. You will never (like me) quite understand it. ![]()