Along with an ever-increasing interest in raising backyard chickens comes the eternal question: Which breed is best? Given the hundreds of chicken breeds in various sizes, shapes, and colors, that question begs another question: Best for what purpose?

If your purpose is meat production, the question narrows to: Which is the best breed to raise for meat? And, for anyone who is familiar only with supermarket broilers, an important question is: What does real chicken taste like?

I have been raising and cooking backyard chickens for 45 years and I still don’t have a definitive answer for either question. But I can tell you what real chicken doesn’t taste like — it doesn’t taste like the chicken found at the average supermarket meat counter.

The breeds I choose for meat are not the same breeds everyone else is raving about. Further, I don’t raise one single meat breed — I raise three.

Roasting Chicken

Chicken meat offered at most supermarkets comes from industrial hybrids developed by combining genetics from two breeds — white Cornish and white Plymouth Rock — and is commonly called the Cornish cross. Food snobs turn up their noses at the white Cornish cross for many reasons. The most often cited reason is the softness and blandness of the meat.

A popular notion is that backyard chickens of other breeds invariably taste better than these commercial broilers. But what many critics don’t take into consideration is that a homegrown Cornish cross tastes infinitely better than the industrially raised counterpart.

Accordingly, for a chicken to roast whole on holidays, I opt for Cornish cross. They’re ready for the freezer in just 6 to 7 weeks. Their white feathers, with no underlying hairs common to other breeds, make them easy to pluck clean, yielding a succulent roaster with crackling-crisp skin.

For my small family, a compact 1.8 kilogram (4-pound) Cornish broiler is a much more suitable size than even a small turkey. Simply rubbed with sea salt and roasted in a hot oven for a mere one hour, the meat of a Cornish cross is positively otherworldly.

Everyday Chicken

Like many backyard chicken keepers, the main reason our family keeps a flock is for fresh, wholesome eggs. So of course we want a breed that lays well. But we have two other important criteria.

We want to incubate our own eggs to replace our old hens from year to year. Because chicks generally hatch in the ratio of about 50 percent hens and 50 percent roosters, half the chickens we raise annually become layers and the other half supply our table with fryers — perfect!

However, choosing to hatch our own eggs eliminates the option of raising any of the popular hybrid crosses (such as Sex Links) that are developed primarily for egg production. Eggs hatched from crossbreeds will not produce future chickens with the same uniform characteristics as their parents.

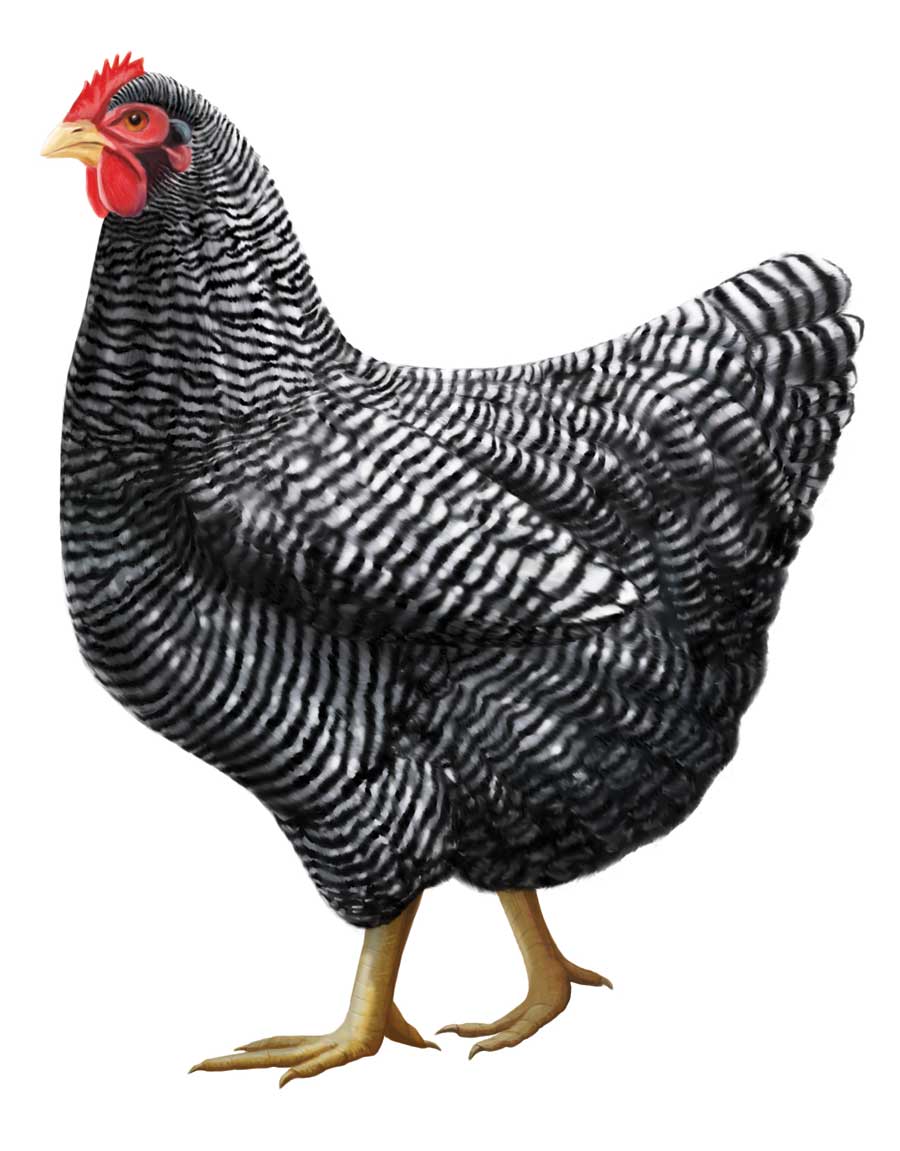

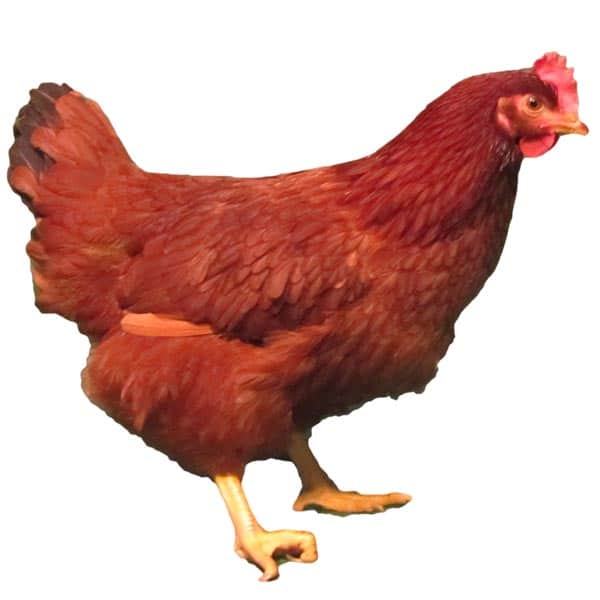

The best producing purebred brown-egg layer is the Rhode Island Red. Now the best egg laying chickens of any breed are notoriously not the best meat breeds, because they have been developed to put their energy into egg production rather than into muscle building. Conversely, the plumpest meat breeds are not the best laying breeds. So, for my family’s purposes, laying ability trumps meat production.

Not only are Rhode Island Reds not considered an ideal choice to grow for meat, but their dark feathers don’t pluck as cleanly as a white-feathered breed would. However, after spending too many hours over the years plucking surplus roosters, I experienced an epiphany of sorts.

Unlike a whole chicken I roast with the skin on, when I cook a fryer I always skin it — so why was I wasting so much time plucking obstinate feathers when I could more easily skin the birds at the outset? Gone, now, are the days when I fussed over unsightly pin feathers.

When harvested at about 8 weeks of age, young Rhode Island roosters produce enough meat to satisfy our family’s everyday needs. The firmness of the muscle and flavor of the meat are decidedly different from the meat of a Cornish cross, but delectable in its own way.

I like to prepare chicken as simply as possible and let side dishes provide variety. My go-to recipe for everyday chicken is to heat a little oil combined with butter in a cast iron skillet. I dip pieces of skinned chicken into the oil, sprinkle them with pepper and sweet paprika, dust them with flour, arrange the pieces in the skillet and roast them in a 218°C (425°F) oven for 15 minutes. Then I turn the pieces and roast for 15 minutes more. Prepared this way, the chicken goes with just about anything I might want to serve on the side.

Specialty Chicken

Decades ago I raised many different exhibition bantam breeds. Eventually I began to focus on utilitarian breeds that produce eggs or meat, or both. A few years ago I decided it would be fun to have bantams again.

A bantam is a small chicken, about one-fourth to one-fifth as big as a regular-size chicken. From among the many available bantam breeds, I had a hard time choosing a single one, but I finally settled on Silkies. The breed name comes from this bird’s fluffy, fur-like feathers.

Now my reason for having Silkies was for pure enjoyment; in other words, as pets. But I soon found them to be fairly prolific layers of pint-size eggs with larger yolks in proportion to the whites, compared to Rhode Island Red eggs. Silkie eggs are perfect for making deviled eggs and for pickling.

When Silkie hens aren’t laying eggs, they keep themselves busy hatching any eggs you might leave in the nest. Soon I was overrun with excess Silkie roosters. So I did what I always do with extra roosters — and discovered why the Chinese are so enamored with Silkie meat. One of the many oddities of the Silkie is that it has black skin, black bones, and nearly black flesh. According to Chinese tradition, eating black chicken meat strengthens the immune system.

A Silkie matures to not much more than two pounds, live weight, so you can image there’s not much meat on the bone. The meat of a full-grown Silkie, as I rapidly learned, is rather dry and tough. But the meat of a young rooster, harvested at about the time you can tell a rooster from a hen, is moist and tender with barely any fat. The flavor is slightly sweet and otherwise quite different from any other breed I have ever raised, but nevertheless is unmistakably chicken.

So what does real chicken taste like? It tastes like, well, chicken.

And which is the best breed to raise for meat? Take your pick. ![]()