The taco has a rival — a corn-based snack that has jumped in popularity outside its native El Salvador.

It is the pupusa, made of the same components as a taco but with significant differences. Instead of a tortilla, the fillings are stuffed inside uncooked corn masa that is then patted into flat cakes and grilled.

The fillings are different too, not carne asada but highly seasoned pork, refried red beans, cheese with edible green blossoms from a vine called loroco or just plain cheese that seeps out and browns appetizingly on the grill.

Pupusas come with a vinegar-laced relish called curtido instead of taco fixings and with soothingly mild salsa, not one turned into an inferno by habaneros and jalapeños.

Pupusas are everywhere that Salvadorans have migrated, and they’re scoring fans outside that group too, because who could resist such a flavor-intense package of food?

In El Salvador, the pupusa is so wildly popular that it was officially named the national dish in 2005. Its history goes back centuries, to the indigenous Pipil people, who filled their masa with beans, vegetables, blossoms and seafood, which are abundant in El Salvador. The name means stuffed or puffy in the Nahuat language.

Later, the conquering Spaniards introduced pork and cheese, leading to the pupusa as it is known today. They also brought in the cabbage and carrots that go into curtido.

In El Salvador, pupuseras (professional pupusa makers) can turn out as many as 20 a minute. Outside the country, pupusas often aren’t as good as they should be, says Salvadoran cookbook author Alicia Maher. And in many places, they are not available at all. That’s because Salvadoran migration, although large for such a small country, isn’t widespread. In the United States, the largest concentration is in California, and especially in Los Angeles, where Maher lives.

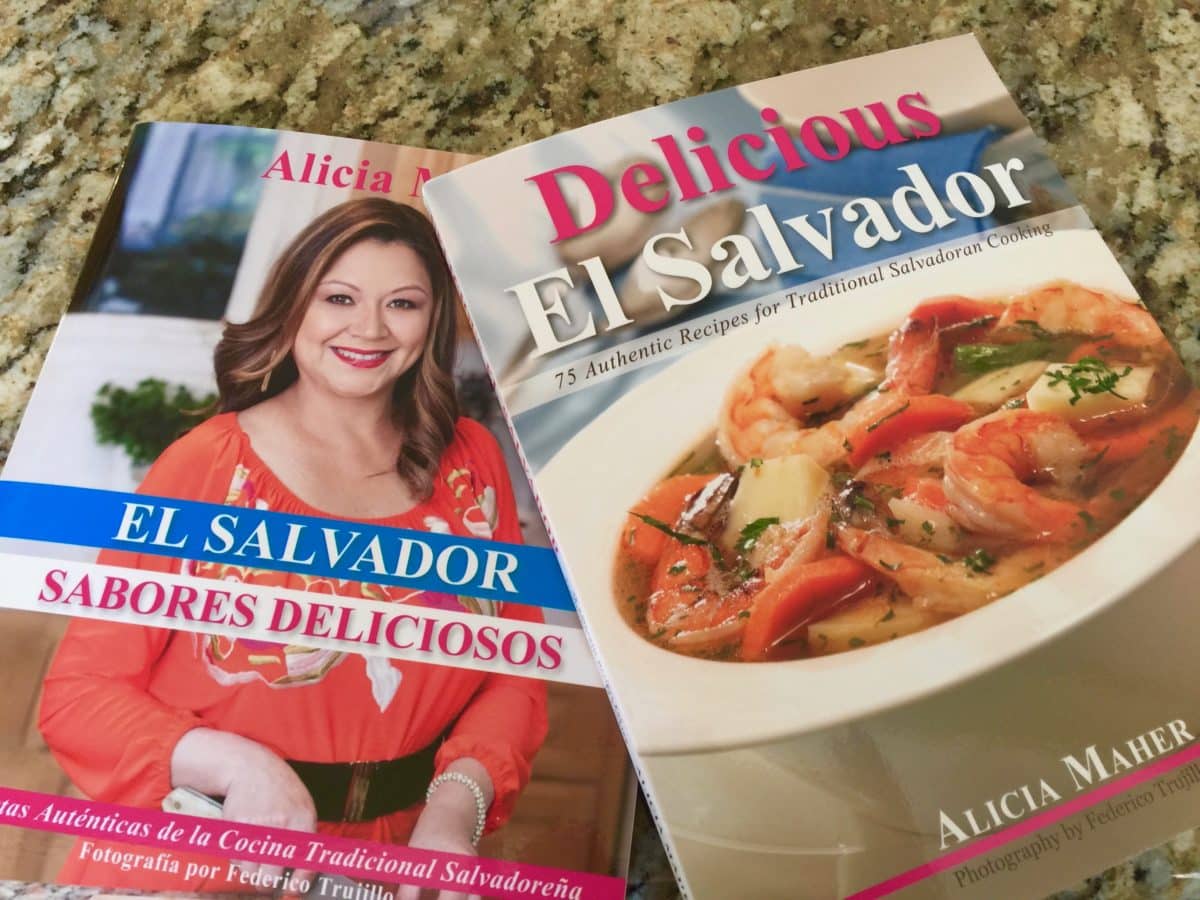

What to do? Learn to make your own pupusas. It’s easy, and Maher explains how in her book, “Delicious El Salvador.” She’s well qualified to teach. Born in El Salvador, she learned to make pupusas by watching how it was done in markets and restaurants. “They don’t have to be perfect. We’re not professional pupuseras,” she says reassuringly.

In the book, she gives the three most common fillings. These are fried pork, which is called chicharrón, refried red beans and cheese. When the three are combined, the pupusa is called revuelta. Pupusas are always served with curtido, which contrasts with the richness of the fillings, and with tomato sauce.

It’s the fillings that go wrong in restaurants, Maher says. The worst offender is chicharrón. This same word applies to Mexican style fried pork cracklings, and that is what some restaurants substitute for pork meat.

To make chicharrón, Maher boils pork shoulder until the water cooks away and the meat fries in its own fat. She then cooks onion, tomato and bell pepper in the drippings, adding the pork. The final step is to grind the mixture until fine in a food processor or blender. It is then ready to fill pupusas.

Unknown content block type: FlexiblePageTemplateFlexibleContentPhotoFullWidthLayout

{

"__typename": "FlexiblePageTemplateFlexibleContentPhotoFullWidthLayout"

}For the beans, she boils small dried red beans with onion and garlic, then fries the pureed beans in oil in which onion slices have been cooked until golden.

For cheese, she suggests Monterey Jack combined with Salvadoran crema (cream) or, as a substitute for the crema, sour cream lightly seasoned with salt. Another idea is to combine 227 grams (8 ounces) of mozzarella cheese with 85 grams (3 ounces) of jack.

Cheese is an area where restaurants economize by using inferior grades, she says. An additional fault is splashing the grill with oil as the pupusas cook. Authentic pupusas are baked on an ungreased grill. Enough fat from the fillings seeps through so they don’t stick.

Curtido and tomato sauce are usually acceptable, Maher says, but restaurants may leave out the ground annatto seeds (achiote) that she puts in the sauce. Salvadoran tomato sauce is not spicy, because hot seasoning is not typical of Salvadoran cuisine, she explains.

Maher can buy authentic Savadoran crema, cheese and red beans in Los Angeles, but these aren’t needed to make a genuine pupusa, nor is fresh corn masa required.

In the book and at home, Maher makes pupusa dough with instant masa flour, because it’s widely available in supermarkets and online. And it’s convenient to keep on hand. She stirs the flour together with water in a large pan, then kneads the mixture until soft and smooth, similar to bread dough.

To fill a pupusa, she forms a hollow in a ball of dough, adds the filling, seals the dough around the filling and presses and pats it until flat. Another way is to divide each dough ball in half, flatten the halves, spread one half with filling and top with the other half, then seal the edges. Pupusas are forgiving. If the dough should crack slightly it is OK, she says. And if a little filling seeps out as the pupusa cooks, that is OK too.

Unknown content block type: FlexiblePageTemplateFlexibleContentPhotoGalleryLayout

{

"__typename": "FlexiblePageTemplateFlexibleContentPhotoGalleryLayout"

}A proper pupusa should be about 10 cm (4 inches) in diameter, Maher says. Restaurants often make their pupusas too large and sometimes put in only a little filling, producing heavy, doughy pupusas. If the pupusa is small, it is easy to eat by hand, which is the correct way.

Watching Maher pat out pupusas in the kitchen of her sunny hillside home makes clear that the task is not hard, even though several components are involved. The fillings can be prepared in advance and frozen or refrigerated, she says. They must, however, be brought to room temperature before using. If too cold, they won’t spread out properly.

The fillings can be used for more than pupusas, she points out. Chicharrón also works as a spread or sandwich filling. Boiled red beans are a staple in Salvadoran homes. When pureed and refried, as for pupusas, they can also be a side dish or spread. When pureed but not refried, they are served for breakfast or dinner, accompanied by fried plantains and Salvadoran crema. Recipes for all three are in her book, which is available through her website, deliciouselsalvador.com, as well as Amazon and Barnes & Noble. There is more about pupusas on the website, including recipes for summer squash and fish pupusas, which are among variations found in El Salvador. There, pupusas are eaten as a snack, not as a main meal, and are bought outside the home, Maher says.

What inspired her to write “Delicious El Salvador” was an online American video in which a chef did everything wrong, from using canned kidney beans for the filling to frying pupusas, which is an absolute no no. Her goal was to make clear how pupusas are actually made as well as to present other typical recipes from El Salvador.

The importance of the project convinced Federico Trujillo, admired in El Salvador for his nature photographs, to photograph the book. Trujillo, who passed away in 2017, is known for the book “El Salvador un Rincón Mágico,” which promotes the attractions of El Salvador. Each recipe in Maher’s book is accompanied by one of his stunning photographs. A few scenes of El Salvador are included as well.

Now in its second edition, “Delicious El Salvador” won the Gourmand World Cookbook Award for best first cookbook in the world in 2014. The next year it won a Gourmand award as best first cookbook of the last 20 years. Maher’s Spanish translation, “El Salvador, Sabores Deliciosos,” has been nominated for a 2018 Gourmand award in the translation category.

The book is also being distributed in El Salvador, where home cooks are latching onto fast food and losing touch with traditional recipes. There, cooking has always been passed on orally and visually, Maher says, and cookbooks are a new phenomenon. ![]()