Sunny and uplifting, a room so full of cheer promises happiness at the table.

The impressionist artist Claude Monet lived at his home in Giverny, France from 1883 to 1926. He was known for painting scenes of his garden, and especially water-lilies in his pond, and his home and gardens are open to the public year-round. I was there very recently, a visit I had looked forward to for a long time.

The Dining Room as Art

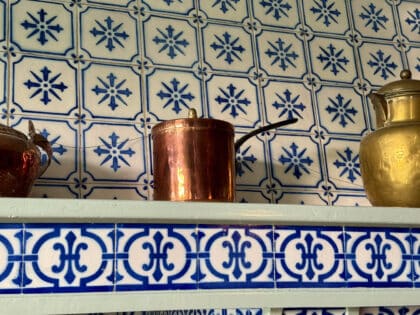

I was once given a lovely book called Monet’s Table: The Cooking Journals of Claude Monet, by Claire Joyes with photos by Jean Bernard Naudin (Simon & Schuster 1989). The blue and yellow cover echoes the colors of Monet’s dining room, shown on the front. The colors are arresting – they make you stop and look and marvel. Who puts such vibrant complementary colors in a dining room? Hazy blue, chrome yellow, pale yellow, and leaf-green trim on doors and railings visible just outside. A tiled floor with alternating squares of terra cotta red and white. A collection of Japanese prints lines the walls. Sunny and uplifting, a room so full of cheer promises happiness at the table.

According to author Claire Joyes, dinner at Monet’s home in Giverny began with a soup course, followed by a dish such as a souffle, then a main course plus salad and cheese. Desserts – compotes, cake, cookies – were served at lunch, with leftovers served after the evening meal.

Monet was particular about when vegetables from his garden were harvested. Fish often came from his pond, wild game was hunted in season, and Paris markets provided ingredients like lobster and monkfish.

What the Cook Knew

With her limited pantry, the cook knew how to make the most of combining foraged and local ingredients with specialities from farther afield. A sauce for roasted venison included two cups of rosehips – no doubt straight from the roses in the garden – with slivered almonds and chopped lemon. Many recipes, sweet and savory, included chestnuts in one form or another. Chestnut puree in cookies and cupcakes, whole peeled chestnuts in oxtail stew. Details could be ingenious, such as a fondant frosting colored bright green with spinach leaves that had been blanched, strained, and passed through a fine sieve.

There were eight children in the house, two from Monet’s previous marriage and six brought from his marriage to his second wife, Alice. The family had a cook, gardener, wine-steward, and others to care for the espaliered pear trees and the apple, cherry, and plum trees, as well as their ducks, geese, and hen yard. Rabbit was often on the menu, but wild game only, so there were no domesticated rabbits. Local farms provided pigeons and meats.

On the day I arrived at Giverny, a steady drizzle lowered the sky, wet the garden paths, and made hanging leaves glisten and drip. It was not an ideal day for wandering among shrubbery, but the gray sky brightened the colors of the trees and fall flowers. A slow but

steadily moving line of visitors moved into the doorway of the house and threaded through an anteroom, storage room, sitting room. I prepared myself to be disappointed. And then my heart jumped. The dining room was just what I had imagined. Instead of tourists, I saw the family.

Eight children running in and out. Windows open, the garden outside, the calls of wild birds and squawking geese, the scent of ripening fruit, earth being turned with a spade. The kitchen had to be busy nonstop, feeding a large family and staff. Did the cook appreciate her spacious kitchen with its pretty blue and white tiles? Did it satisfy her to see the family gathered in the bright dining room, enjoying the results of her hard work? I have to think it did. I like to think so. ![]()

Unknown content block type: FlexiblePageTemplateFlexibleContentPhotoFullWidthLayout

{

"__typename": "FlexiblePageTemplateFlexibleContentPhotoFullWidthLayout"

}