There was frost on the ground in Chicago when I left for St. Croix, and I was glad to be going. I’d moved to Chicago about six months prior to complete the final requirements for a doctorate in clinical psychology, which involved a year of heavily supervised field work at a private practice. Things at the practice were going poorly and I was miserable, with my writing becoming a shelter from a storm raging in my daily life. I felt chilled in body and spirit and when the plane’s wheels lifted from the tarmac and set off toward my transfer point, Miami, I could think only of sunshine.

Arrival on the island was easy and I soon found myself standing, slightly disoriented, outside of the airport in Christiansted, the largest town on St. Croix. The weather was hot and humid and a strong breeze wrapped me in the scent of lush tropical foliage intermingled with exhaust from idling vehicles. As I waited for my pickup a person in a booth offered me a free shot of Cruzan rum, one of the island’s most famous exports. Moments later my vehicle arrived and after a brief but warm introduction we set off. It did not decrease my disorientation when, less than ten minutes later, I sat with a mountain of food in front of me at La Reine Chicken Shack, one of the island’s most famous culinary institutions.

At the time I didn’t fully comprehend just how quickly the sequence of arrival-booze-food had happened, but now, having gained just a sliver of knowledge about St. Croix and its people, I’m not at all surprised. The people of St. Croix seem characterologically driven toward hospitality, and the reasons for this are diverse.

“St. Croix is a magical place and I’m not using that word lightly.” Later, after returning to Chicago I called Tanisha Bailey-Roka, a prominent Cruzan (or Crucian, as either spelling is acceptable) who is both an attorney and a food blogger known as the Crucian Contessa. I’d contacted Bailey-Roka before coming to the island as she stood out online as a local authority on food, and I’d had the good fortune to meet her several times over the course of my trip.

Now that I was back in the land of wind and ice I was struggling to find a central focus for my story, and she was generous enough to help me make sense of my experiences on St. Croix. We’d been speaking for fifteen minutes about what visitors to the island might experience upon arrival when she said, “You will taste the food based on the land, you will taste the food based on the history, and you will taste the food based on the diversity of the people in the kitchens.”

Fireworks went off in my mind. St. Croix’s remarkable food — and it is remarkable — was not just because of environment, or because of history, or because of craft and skill. It was because of all of these things, locked together to form a complex web of cultural terroir.

The word “terroir” generally comes up when we think or talk about wine, as it represents how factors like soil, geographical location, and climate can impact the growth and development of grapes, and ultimately the flavor of the wine. Terroir is also about culture though, and about the back-and-forth interplay between people and their food, where food comes from culture and culture comes from food.

It’s a phenomenon that exists in every culture and is certainly not something exclusive to St. Croix or to the U.S. Virgin Islands. That being said, St. Croix’s cultural heritage is particularly deep, though, and reflects not just its connection to the United States but also to the part of the world it inhabits.

The three islands of the U.S. Virgin Islands (the USVI) — St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John — are located in the Caribbean about 40 miles east of Puerto Rico and lie close to the British Virgin Islands. While they celebrated their centennial this March, signifying one hundred years as a protectorate of the United States, their history is reflective of the tumult common to the Caribbean during the pre-industrial age of European empires. St. Croix belonged to at least six other countries, including Great Britain, Denmark, Spain, the Netherlands, and France. Colonization efforts lead to war with the native peoples, a mix of Caribbean ethnic groups known as Arawaks, Ciboney, and Carib, and also lead to an eventual mixing of cultures. Another byproduct though was the development of agriculture. Agriculture was supported by slavery, particularly in regards to the production of sugarcane to make both sugar and rum, and this, combined with the island’s general location, lead to a melting pot of European, African, Asian, and native cultures and traditions.

Today St. Croix is known as the culinary hub of the U.S. Virgin Islands, and culture and environment play a significant role. According to Bailey-Roka, the island of St. Croix produces particularly vibrant agricultural products thanks to a lack of industrialized farming and a tendency to avoid heavy pesticide use. Fertile soil, high humidity, and consistent sunshine also contribute to the island’s verdancy. “We’re seeing a reversion back to agriculture,” said Bailey-Roka, “an understanding that the land is important and can bring so many beautiful things.”

The island’s modern food culture is also heavily influenced by what’s available from the surrounding sea. While overfishing is a threat in any fishery, both man and nature can influence what’s on Crucian plates. When Hurricane Hugo hit the U.S. Virgin Islands in the late 1980s the storm leveled a significant portion of the area’s reefs and deeply injured the island’s underwater ecosystem. Strong efforts are now being made to help preserve sustainability.

Kemit-Amon Lewis, another St. Croix-native, works as Coral Conservation Manager for The Nature Conservancy, a member of the Reef Responsible Sustainable Seafood Initiative. “St. Croix is pretty special for a number of different reasons. The reefs around the island are very important for a lot of the seafood that we consume.”

Lewis and his colleagues have invested time and resources encouraging local fishermen to engage in responsible fishing, which they believe is one of the primary ways of helping to preserve the biodiversity of the island. They strive to have both fishermen and restaurant purchasers consider fish which might not traditionally be served. Diners and restaurants tend to gravitate toward parrotfish, snapper, grouper, conch, and lobster, with deep water fish such as mahi, wahoo, and tuna appearing on menus as well. Reef Responsible is focusing efforts on creating a market for lionfish as an alternative, as they’re an ecologically responsible and sustainable alternative to more commonly fished varieties.

While it’s challenging work to change the habits of diners, Tanisha Bailey-Roka says that culinary change is a part of the island’s history, and is not something people necessarily shy away from. “While it is traditional, it’s also dynamic, and it’s changing.” During a dinner at balter, one of St. Croix’s most well-regarded restaurants, noted chef Digby Stridiron spoke about turning away a fisherman who came to him with undersized lobsters. While there’s no question of his being able to sell what fishermen bring to him, it’s not how his restaurant seeks to do business. It’s this type of behavior Reef Responsible is hoping to encourage, and which has the potential to change buying patterns on the island.

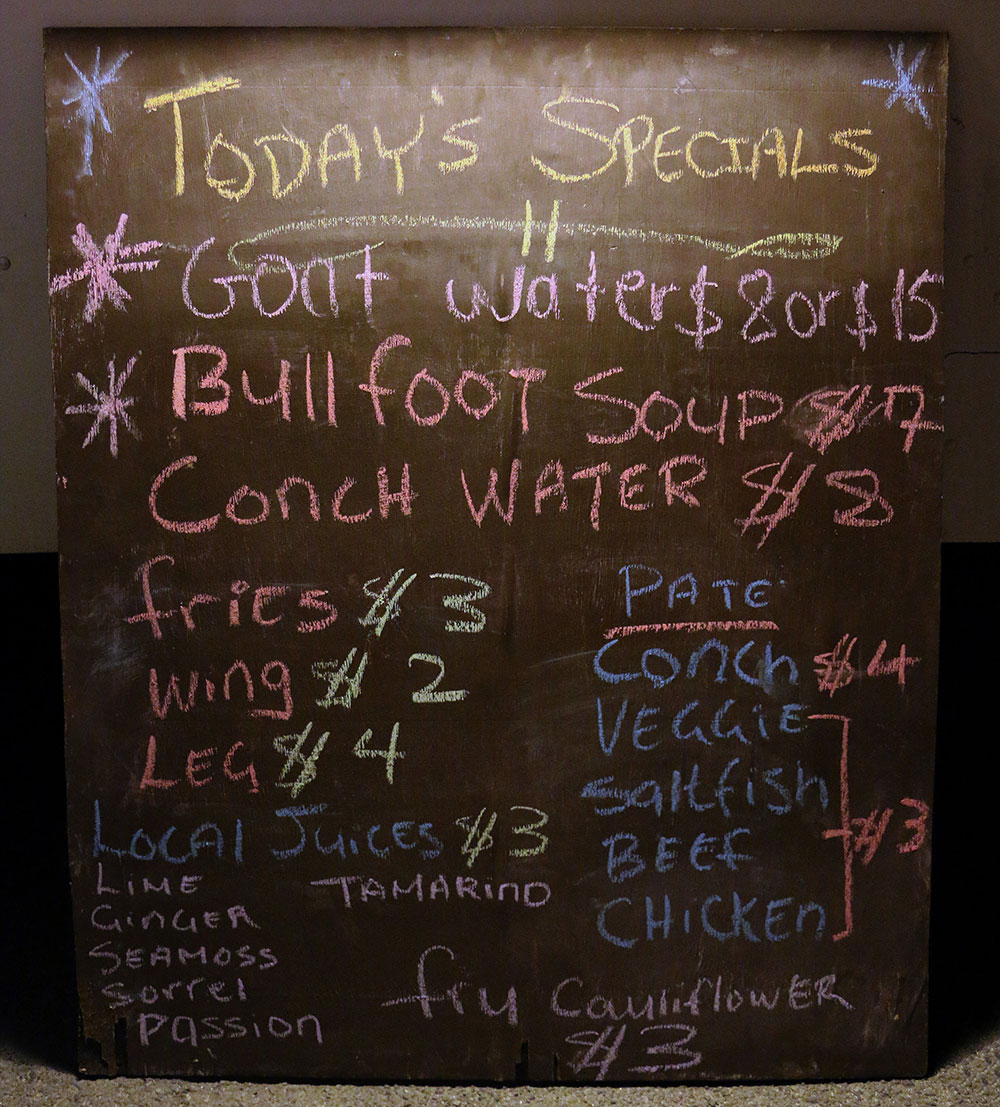

Bailey-Roka believes the island’s diversity is the key to understanding both its past and its future. “Including all the cultures that have come to St. Croix we have such a diversity,” she said. “Our kitchen mothers, and maybe some of our fathers, were very inventive.” Now that same inventiveness is coming out in new ways. The town of Frederiksted hosts an annual food truck festival which serves up traditional dishes like pate, which uses the same pronunciation as the French meat terrine but is actually a large, deep-fried empanada. Drinks made with locally harvested fruit, herbs, and bush leaves also appear, as do soups, fried fish, and smoked barbecued meats. Simultaneously, fine dining restaurants like balter utilize traditional ingredients like breadfruit, plantain, and local fish in new and inventive ways.

There are a great many places in the world which have experienced a blending of cultures and traditions, and where fusion is evident in the cuisine being served. The particular history of the U.S. Virgin Islands makes it unique though. Visitors will find a dining destination whose culinary vision is expressed in what was once available, what is available now, and what might be available in the future. It’s exciting, and it’s changing, and it would be a loss not to experience it yourself. ![]()