My girlfriend Jim apologized for inviting me to an Italian restaurant for our lunch date. When I visit Bangkok, she is one of my favorite dining companions because she shares my love of Thai food. Together with her faithful driver, John, they make great food detectives with a knack for finding Thai eateries that are hidden gems, not only in the city itself, but also in surrounding areas. During this past decade we have feasted on incredible Thai meals together, meals that could instantly transport us back to our childhood days.

During our lunch, Jim lamented that the Thai restaurants we both love are fast disappearing from Bangkok. She predicted that very soon the older generation of Thais, like us, who grew up eating traditional Thai cuisine, would have to travel to other countries to find our favorite Thai dishes. It seems foreign chefs are fast becoming the experts in our country’s cuisine.

Other Thai friends share the same sentiment. Once, it was only a matter of choosing which restaurant to go to if one wanted to feast on an exceptionally prepared dish by a talented cook. Nowadays the choices are slim, and often we end up dining at European restaurants such as the Italian restaurant where Jim and I had lunch.

Most of my Thai friends do not cook. However, raised in families with great cooks and culinary experts, they were trained to recognize the conventional tastes, flavors, and aromas of Thai cooking. My friends have refined senses and taste buds capable of detecting the slightest nuances of hidden ingredients in the simplest to the most complex dishes. Their appreciation and expertise exemplifies an important cultural education in Thai families, a heritage passed down from generation to generation. This traditional relationship to authentic Thai food makes them passionate about our country’s cuisine.

They are also merciless food critics and proud of it. To them, Thai culinary arts are a national treasure, a treasure that many fear is vanishing. I must admit that, in many ways, I agree.

The issue is not that if you visit Thailand you would not find Thai food. Bangkok, like the rest of the country, is inundated with countless varieties of Thai foods, not only in restaurants but also in food malls. There are food cart vendors parked everywhere — on sidewalks, alleys, or, in fact, any open space. It’s not the lack of Thai food, but its rapid and revolutionary transformation that has us worried.

Time is Taking a Toll

The tastes of central Thai cooking, the meals enjoyed by my generation, are almost extinct, and so are the traditional Thai restaurants we once favored. Our food has been abducted — gentrified. One of the biggest culprits behind this change is time. Thais have come to embrace the Western concept of time. Cooking Thai food was once a family affair, done by several members of a family or hired cooks as a part of their daily routine.

Family-run restaurants were started by talented cooks as a way to make a living. Older entrepreneurs who had opened their renowned restaurants decades ago were able to recruit and keep younger cooks who had learned their trade in their homes from cooking for their families. In return for their loyalty, these cooks were often treated as members of the family business.

Unfortunately, today, in Thailand, cooking has become just another chore – a burdensome one-person chore at that. This is true even for those fortunate enough to have a paid cook in the family. When one person is cooking dishes that once took several people to prepare, a cook’s time has to be well-planned, and the work can be exhausting.

For family-owned restaurants, as the cooks got older and could no longer handle the heavy work load, the families simply quit the business. One might think that the younger generation in these families would wish to continue the tradition. However, having benefited from the business’s prosperity and encouraged by their family to advance themselves, many of these youngsters chose professional careers over slaving in the kitchens like their elderly relatives. As for restaurants that relied on self-trained cooks, if these individuals quit, finding their replacements became nearly impossible.

Once, young people from the outer provinces who came to Bangkok in search of work would do anything. Today, they are more selective, preferring to work in the hospitality business or factories where they find higher pay, less stress, and more time off.

Shortcuts Shortchange Tradition

The new focus on time has introduced a virus that is undermining the Thai cooking tradition. It’s called the “shortcut.”

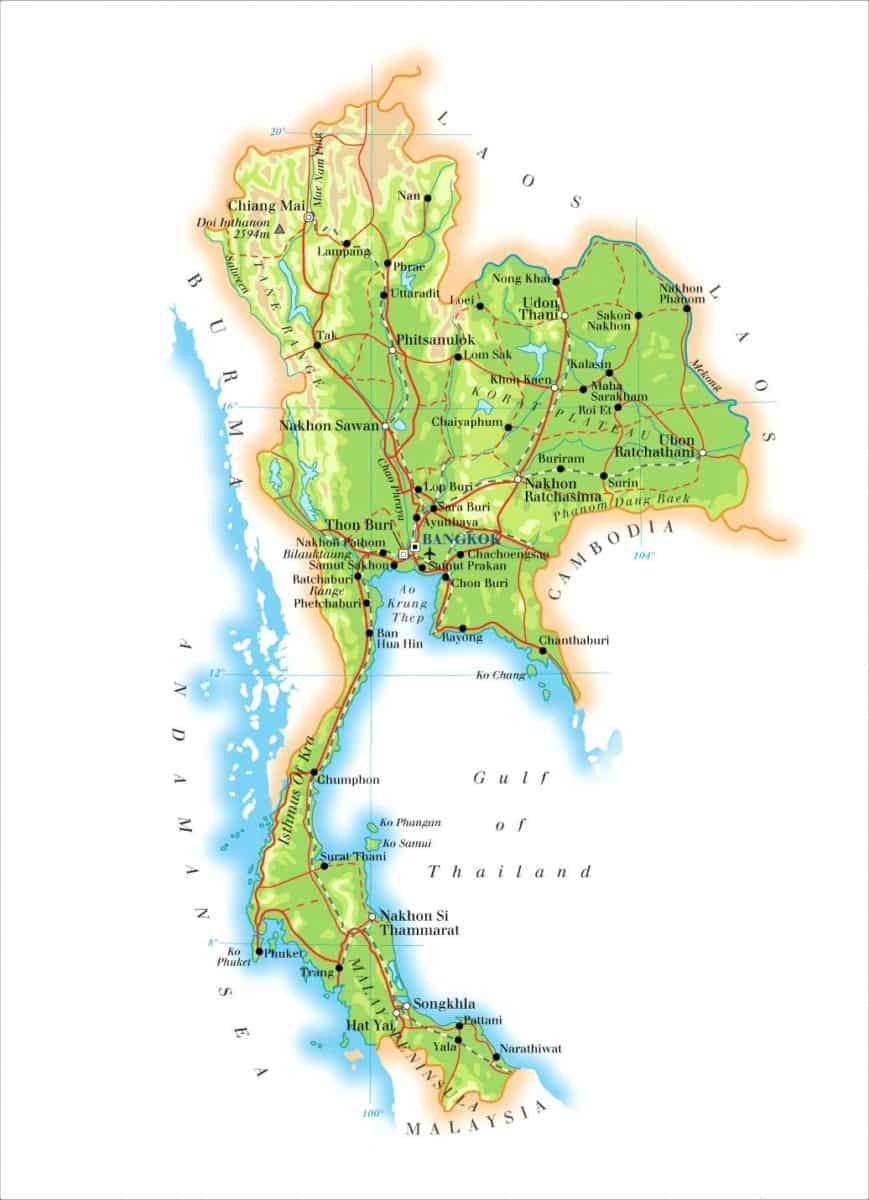

Preparing a dish with the perfect ingredients is one of the ancient rituals important to Thai cooking that has suffered from the shortcut. For example, the best cooks did not buy basic staples from a market. They went directly to the source or the grower. They sought the purest palm sugar produced from the lush and fertile city of Petchburi, salt from the seacoast city of Trang, and fish sauce and shrimp paste from another city by the sea, Rayong.

Shortcuts have also spread to the cooking process. Today, Thais are simply too busy, slaves to Western dictates of the hurried and harried life. There is no time to cook the way the old-timers once did. Although Thais all still love to eat really well, we have compromised, settling for convenience.

Convenience Rules

Shortcut’s allies are store-bought foods that are fast and easy to fix. Consequently, younger generations, brought up with these compromised and gentrified Thai foods, have developed a different palate. To them, food cooked and sold by vendors or prepared in modern restaurants or food malls is the “real” Thai food.

Take coconut cream, for example. Once upon a time, all cooks grated the fresh and mature meat of a coconut, pressing and making the rich coconut cream and milk minutes before it went into the pot for cooking. For special dishes that required a rich, thick, and creamy coconut cream, only a special variety of coconut called “maprow” (coconut) “gathi” (cream) was used. Cooks either shopped for the coconut themselves or relied on a trustworthy vendor to deliver several kilos of coconuts that were stored in the kitchen.

As mechanization took hold after the Second World War, markets began to sell freshly grated coconut. Vendors operated a huge machine that hummed like a hungry swarm of insects, feeding it with coconut flesh hauled out of hard fibrous husks. The machine chewed and ground the meat into mounds of grated coconut flakes. For dessert recipes, which required the pure white coconut cream, the vendors would chip away the outer brown peel before feeding the flesh through the grater, producing snowy coconut flakes for milking.

This new invention offered an alternative to cooks, shortening the laborious process of cracking and grating the coconut meat themselves. Home cooks and restaurateurs needed only to buy the freshly grated coconut, bring it home or to the restaurant, add some warm water, press and squeeze, and, voila, one had freshly pressed coconut cream.

However, today, even the coconut-grating vendors are being abandoned as artifacts of the past like coconut milk become instantly accessible and drinkable.

Coconut, with its a newly-acquired status as one of the healthiest saturated fats, is being exported by the tons, making it not only scarce but also expensive for Thais to purchase. To make matters worse, some genius thought of a way to process coconut cream so it will keep for months. Cooks in a hurry, on the spur of a moment, can now speed into an air-conditioned space, be soothed with piped-in music at a convenience store such as a 7-Eleven, and grab a pasteurized can or carton of coconut cream.

I am told that some cooks even use dairy products as a substitute for coconut milk, thinking that a touch of “farang” or foreignness will make their Thai food more chic. The richly flavored, creamy textured, and aromatic fresh coconut cream, once highly valued and considered one of the most important ingredients in Thai cooking, has been downgraded and degraded.

The Future of Thai Cooking: Two Different Views

I pondered over Jim’s lament, wondering how strange it is that, as Thai foods become the latest rave to the rest of the world, younger Thais simply do not care enough to properly cook and preserve this ancient tradition.

Then as luck would have it, I happened later to run into an old friend who had been a highly respected cooking teacher. Like Jim, she expounds unceasingly on how Thai cooking is being ruined. One of her main complaints is that loads of sugar are being added to every dish. She is equally critical about cooking shows that are the rage on television, asserting they are spreading ridiculously false information on how to cook Thai food. One particular show caught her attention. It starred a Thai chef who works at the Oriental Hotel, where I was staying.

She suggested that I interview him to see “if he knows his stuff.” I was naturally skeptical because Thai food served in hotels, no matter how refined, expensive, and elegant, is known for being doctored for “farang” or foreigners. My friend had never eaten a Thai meal at the Oriental Hotel, and, when invited, had politely declined. For that matter, neither had I. But she egged me on and I relented.

Ms. Karn Puntuhong, of the hotel’s public relations office, was gracious to arrange an interview with the television show’s star chef, Vichit Mukura. She also suggested and arranged for me to attend the hotel cooking school taught by another expert cooking instructor, Narain Kiattiyothroen. This turned out to be a wise suggestion and made for a vastly interesting interview because these two men, both in the same age group, have very different perceptions regarding the future of Thai cooking.

The cooking school is located across the river from the hotel in one of the well-preserved, turn-of-the-century, wooden Victorian homes.

The classroom is elegantly furnished and well equipped with the main prepping kitchen discreetly hidden from the view. The students were visitors from Germany, Holland, Spain, and America. And then there was me, mistaken by the young staff scurrying back and forth between the prepped kitchen and classroom as a Japanese tourist.

Chef Narain came to his cooking profession late in life. Brought up in a Chinese family, he worked for decades as an English teacher at one of the prestigious Thai universities until he decided on a career change. He attended a culinary apprenticeship program offered by the Oriental Hotel, graduated, and worked his way up to be one of their best cooking teachers. Assisted by staff members as well as the seven students during our three-hour morning class, he taught four recipes: stuffed cucumber soup; rice vermicelli with coconut cream sauce; fried baby shrimp encrusted with minced herbs, spices, and cashews; and sweet potato cooked in coconut sauce for dessert.

The class is a combination of demonstration and hands-on application, followed by a lunch consisting of the dishes we cooked. With most of the time-consuming ingredients, including seasoning paste, crispy fried herbs, spices, and freshly pressed coconut cream having been made ahead, Chef Narain went through each recipe with great precision. It occurred to me that it was unfortunate that all of the attending students were unfamiliar with Thai cooking techniques and would not know how to re-create the prepped-ahead ingredients.

Chef Narain professed high hopes for the future of Thai cooking. He readily acknowledged that he did not know too many young people or friends his age who cooked Thai food regularly at home. He also agreed that, for convenience, Thais tend to eat out too much. In all his years teaching cooking classes he has never had a Thai student. However, he is proud that Thai cooking is valued among foreigners. He thought it wonderful that many Thai cooking experts today, and in the future, will be foreigners.

His optimism is based partly on his experience with the young staff members who work under his guidance. He felt that although they might not have wanted to join the Thai cooking program at first, once they became apprentices they were enthusiastic and eager to learn. (Thai cooking ranks the lowest in popularity at the school, with Western baking ranking highest.) Furthermore, he cited himself as an example. Coming late to the art of cooking Thai food, he had been only vaguely familiar with the long centuries of the cultural significance Thai food has played in our country’s history. He also had not known how to cook the complicated and elegant central Thai dishes, especially those that had their origins in the Royal Court.

Watching the students, I was impressed with three of the four, who expertly displayed their cooking skills. They were curious about Thai food, loved eating it, and were eager to learn how to do everything right. They were home cooks who had tried their hand at cooking Thai recipes on their own. The fourth student was a German restaurateur. She knew nothing about Thai cooking but had a notion that Thai food is healthy and popular, and she plans to serve it in her restaurant in Kauai. For all four students, the main deterrents to cooking Thai food seemed to be the prepping time, mastering Thai cooking techniques, and the ability to purchase the necessary ingredients in their homeland.

Chef Narain professed high hopes for the future of Thai cooking. He readily acknowledged that he did not know too many young people or friends his age who cooked Thai food regularly at home. He also agreed that, for convenience, Thais tend to eat out too much. In all his years teaching cooking classes he has never had a Thai student. However, he is proud that Thai cooking is valued among foreigners. He thought it wonderful that many Thai cooking experts today, and in the future, will be foreigners.

His optimism is based partly on his experience with the young staff members who work under his guidance. He felt that although they might not have wanted to join the Thai cooking program at first, once they became apprentices they were enthusiastic and eager to learn. (Thai cooking ranks the lowest in popularity at the school, with Western baking ranking highest.) Furthermore, he cited himself as an example. Coming late to the art of cooking Thai food, he had been only vaguely familiar with the long centuries of the cultural significance Thai food has played in our country’s history. He also had not known how to cook the complicated and elegant central Thai dishes, especially those that had their origins in the Royal Court.

Chef Narain professed high hopes for the future of Thai cooking. He readily acknowledged that he did not know too many young people or friends his age who cooked Thai food regularly at home. He also agreed that, for convenience, Thais tend to eat out too much. In all his years teaching cooking classes he has never had a Thai student. However, he is proud that Thai cooking is valued among foreigners. He thought it wonderful that many Thai cooking experts today, and in the future, will be foreigners.

His optimism is based partly on his experience with the young staff members who work under his guidance. He felt that although they might not have wanted to join the Thai cooking program at first, once they became apprentices they were enthusiastic and eager to learn. (Thai cooking ranks the lowest in popularity at the school, with Western baking ranking highest.) Furthermore, he cited himself as an example. Coming late to the art of cooking Thai food, he had been only vaguely familiar with the long centuries of the cultural significance Thai food has played in our country’s history. He also had not known how to cook the complicated and elegant central Thai dishes, especially those that had their origins in the Royal Court.

He learned about both – the cultural value of Thai foods and preparation of the royal dishes – through his apprenticeship. Now, today, he is committed and able to pass on this knowledge to his staff and students. To him, and through him, Thai food tradition will prevail, although not exclusively among Thais.

Chef Vichit, the television star, is the executive Thai chef and consultant for the Oriental Hotel. He came from a humble background, growing up the youngest child of a large family in the beach resort of Pattaya. To keep an eye on him, his mother took him everywhere with her. She was a typical Thai housewife, who was also a good cook. His father worked in Bangkok and was home only on weekends. Chef Vichit spoke nostalgically about time spent with his mother. It was during these short sixteen years before she died that he fell in love with cooking.

When old enough, he was given the responsibility to rise at dawn with his mother to start the charcoal brazier. She taught him how to cook, starting with one of the simplest and most beloved Thai dishes – a fried egg perfectly laced with outer edges crispy and crackling, nestled within the golden and raw yolk. She also taught him to grow and select fresh herbs and vegetables from their kitchen garden. He helped her look after the flock of chickens that his mother raised for extra income. He even learned to slaughter them.

He especially loved his mother’s green curry. As he described how she pounded the paste, I could almost smell the fragrance coming from the mortar as he slowly named each ingredient his mother added. Today he has proudly duplicated his mother’s recipe, which is served to guests at the Oriental Hotel.

When money was tight after his mother’s death, like most men of his generation he quit school and started to work as a cook’s helper in Chinese restaurants and hotels. There he learned more about Chinese food and Western cooking. However, it was the mystery of how to roast a perfect Chinese-style duck that captured his imagination and fanned his desire to be a chef.

The chief cook where he was employed at the time was not willing to share his skills. He detected the young man’s ambition and deliberately kept him away from the kitchen. However, Vichit was smart, determined, and possessed keen observation skills. Experimenting through taste and smell, he would work at cooking the duck at home until it was perfect. The secretive way in which the other cook kept his techniques and recipes actually opened Vichit’s eyes to his budding talent as a cook, and a desire to learn more. It also taught him it was time to leave and try his luck in Bangkok.

His next job was at another prestigious hotel for a couple of years before moving on to the Oriental, where he has worked for the past 27 years.

Like his fellow chef, Narain, he is bothered that Thais, especially the young people, are no longer taught how to cook. Their changing values also concern him. Vichit believes that modern Western-style living space is inhospitable to Thai cooking. He jokingly spoke of what a sight it must be to pound seasoning paste, using a huge granite mortar and pestle, on a tiled kitchen floor in a tiny condominium, or how difficult it would be to stir-fry something spicy in a tight indoor space without choking on the fumes.

Unlike Chef Narain, Chef Vichit is disheartened to see the future of Thai cooking dominated by foreign chefs. “They might learn and master the basic technical skills,” he explained with great conviction, but added that they will never acquire the “tongue” or the palate that is an essential quality in a good Thai cook. He feels that Thai cooking does not come from a culinary school, but rather from a traditional Thai childhood, starting with observing, helping with cooking, and eating with family and friends.

Aside from Chef Vichit’s very busy work schedule, he devotes his personal time to an educational program for young children. He has bought a piece of land where he grows rice, organic vegetables, and herbs. He plans to work with schools so that city children can visit his farm. He hopes that through field trips they will learn first-hand how foods are grown. He wants them to taste the fresh produce plucked from the earth and to appreciate how hard it is to grow rice. In other words, he wants them to know the real food from the processed and store-bought foods they are eating. He wants to gift them with what his mother once gave him as a boy. By guiding this new generation of children, he hopes to capture their imagination and train them not only about the land, the food, and the cooking, but to train the “tongue.”

Regrettably, I was fasting in preparation for a long air flight, so I was not able to try Chef Vichit’s green curry. However, I look forward to doing so when I return to Bangkok in the near future. I will invite Jim and my former teacher friend to come with me.

What is happening to Thai food is a sad affair. The trend and changes are irreversible. Cooks like my elderly friends and I are old relics. Once we are gone, our knowledge as cooks will be lost.

However, instead of reminiscing and lamenting, I hope we will band together to cook often and regularly, and to teach while we can. While some of the ways we once cooked — using charcoal braziers or stir-frying in an outdoor kitchen — may be gone, we can still contribute. We can adapt and use our smarts to alter some basic techniques without ruining the integrity of the food.

At the same time, we must be firm to insist and hold on to the cooking methods that preserve the true taste of Thai food. As old cooks, cooking together, we can take turns grating and milking the coconut, or pounding the seasoning pastes in the mortar and with a pestle. Most importantly, we must share our joy of cooking and eating with the young ones. In addition, when we visit the provinces known for their exceptional and special ingredients, we should buy a truckload of products and bring them back to share, to help educate the younger generation, train their “tongues,” and to remind ours to remember. ![]()