For me, coffee is an interesting connection between my American life and my Colombian one.

I come from a long line of coffee enthusiasts. Christmas, birthday, and vacation presents regularly include bags of artisanal blends or special espresso machine equipment. My family always offers a warm mug of fresh brew with dessert, or sometimes in lieu of dessert. In my life, coffee represents a moment of solitude in our chaotic world. It represents late night chats or late night studies. It’s the first smell in the morning, the smell always lingering on my dad’s clothes, and the smell in the office that tells me it’s time to wake up and get to work. As a New England native, it’s the smell of a rushed Dunkin’ drive-thru run or a rainy, cold morning soccer practice. It’s the smell of a dark café with local artwork lining the walls, the sound of loud espresso machines buzzing and milk frothers screaming. Coffee is what my favorite teachers drink in dripping, condensation- stricken plastic cups sitting on the corners of their desks. It’s an offering to appreciate them: a gift card to a favorite coffee shop. Coffee is quick, grabbed at a pick up window or a drive thru, or brewed within a minute in an overpriced espresso machine. It’s instant gratification, a bolt of energy, or a delicious cold and crisp sip.

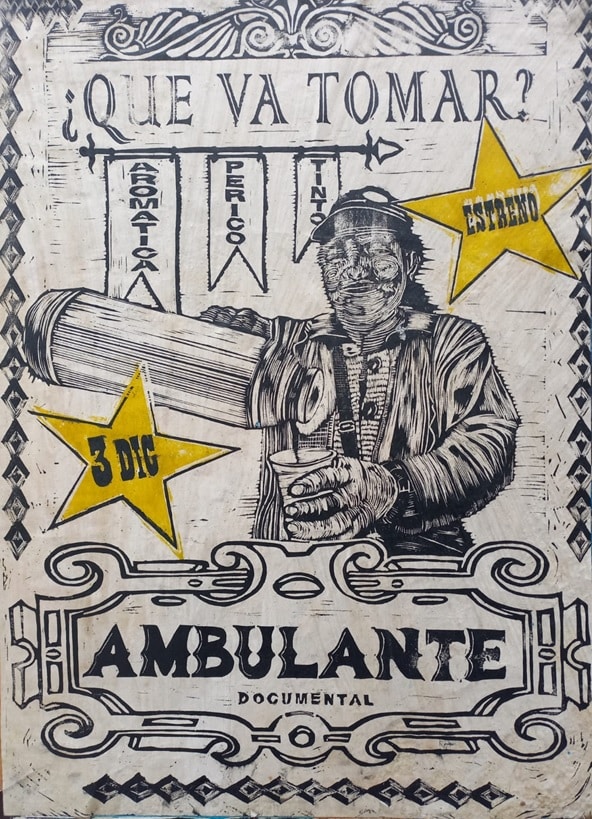

Much like my experience with coffee in the United States, coffee in Colombia acts as a unifier. But unlike coffee in the U.S., it is an art of patience. The Colombian tinto, a dark coffee served piping hot, is as much of the Colombian identity as it is a way of life. Tinto is prepared on the stove in a metal pitcher. The method of preparing it varies: some use a filter, some use instant coffee, some add spices like cinnamon or anise, and some add sugar right away into the mix. Whichever way it’s prepared, it is always an offering.

At the school, “we’re going for a tinto” means we are going to take a break. It means the teachers want to sit with me, converse with me and laugh with me. The day I received my monogrammed coffee mug from the coordinadora (equivalent of a vice principal in the U.S.) was the day I knew I had been officially accepted as part of the school. Colombian etiquette states, “whoever invites, pays.’. If you hear the words, “Te invito a un tinto,” you know those are words of peace, an amistad, or an alliance in the making.

Tinto is what my host mom offers me after a long day at school or an early morning. It is a moment for us to share together, to talk about our lives, or our work, or the world in general. It is our special moment of exchange outside of the chaos. Tinto conversation can revolve around anything: politics, faith, language, or personal experiences. It will last as long as you want it to, sometimes until you reach your third or fourth cup.

Tinto is what we used to escape the hot Atlántico sun during a grueling pre-service training (PST), dipping into the only cold, air-conditioned building in our small town for a few hours of relief. After long business meetings, tinto is what we drink to seal the deal. Occasionally beer is also offered, but tinto is universally accepted. You may sit in a cafeteria or in a tienda at a small table. The tinto will be delivered in small white plastic cups on little plastic trays. Accompanying the tinto, you’ll find a long paper tube of sugar or panela and little straws to stir. The cups are thin, making you wait a minute or two before picking up the piping hot beverage.

I remember one of the first dates with my partner at the panadería in town. We sat at a metal table and ordered two tintos: your standard Colombian socializing. I was new to Colombia, and nervous about the acceptable preparation of a tinto. Is it cool if I add sugar, or is it weird? Is it weird if I don’t add sugar? I waited for his example, but I think he was waiting to see what I did. I decided not to add sugar to be safe. I needed to appear laid back of course! He was surprised by me not adding sugar. “Really?” he asked. Well… at that point I couldn’t back down or show insecurity. I insisted I liked black coffee then proceeded to take a big sip of the darkest, most bitter coffee I’ve ever had in my life. I might have winced; I hope he didn’t notice. With time, I’ve learned sugar is perfectly acceptable. Some people even prefer two packets.

For me, coffee is an interesting connection between my American life and my Colombian one. Coffee is ubiquitous in both places. In America on the macro level: big neon signs advertising special lattes with seasonal flavors or fancy brewing methods. In Colombia, it’s on every corner, at every restaurant and in every household. There is no need for the neon signs; everyone knows where to find tinto. There is no need to complicate it; a tinto is delicious as is.

Drinking tinto has reminded me of the beauty and simplicity that can be coffee. It has reminded me of the very reason I started drinking coffee to begin with: to both socialize and to take a moment of solitude from life. As I sit here writing, I am offered a cup of tinto by my host mom. Another small gesture of kindness in the whirl of my Peace Corps experience. I will gladly accept it, and if I’m lucky, might find myself offered a hot arepa or an empanada to accompany it. ![]()