Alicia Kennedy’s recent book — No Meat Required: The Cultural History and Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating Is not a food memoir or cookbook.

No Meat Required: The Cultural History and Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating by Alicia Kennedy (Beacon Press 2023 ) is a well-researched, thoughtful argument for changing the way we have learned to view the centrality of meat in our diets. It is not a manifesto or prescriptive plan for eating. The book is about food justice. It is a guide to making informed decisions around where food comes from and who is profiting from it.

I was drawn to it by author’s thought-provoking newsletter, the title, and the beautiful cover.

Kennedy analyzes the motivation of movements focused on changing the way we consider the proteins we consume. She presents vegetarian, vegan, and plant-based movements in historical context and examines the political and cultural motivations of proponents of meatless meals. She prods the reader to consider how personal consumption can be viewed within “a framework that considers how policy, global trade, geography, demographics, and media determine what and how we eat, as well as what and how we desire when it comes to food.” The overwhelming message is the debunking of the fake meat industry.

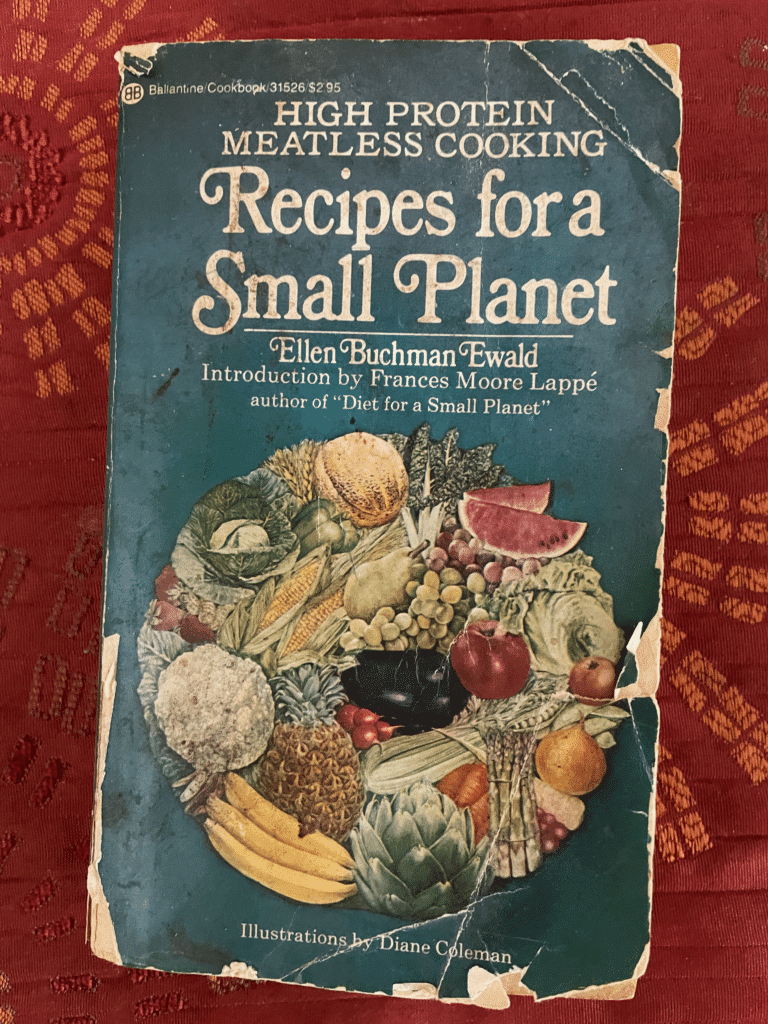

As a baby boomer who came of age in the hippie days of vegetarianism, the references to well-worn, dog-eared cookbooks on the back of my shelves from the 70s and 80s were fascinating and informative.

My early interest in vegetarianism was a mild rebellion to the meat-centric meals of my childhood. For parents who lived through the Great Depression, a hunk of beef was a status symbol. Adulteration by spices or condiments or preparations was forbidden. Giving up meat was viewed as a sacrifice. At that time plant-based cooking also suffered from the same dogmatic attitude and lack of imagination. From this history, I was happy to learn that the mandatory brown-rice-and-bean complementary protein combo theory has been amended over the past 40 years. Successive printings of the 70s vegetarian cookbook classics have been updated. Kennedy’s descriptions of punk vegetarian restaurants in NYC were nostalgic reminders of my teenage years. The 2004 round up review of vegetarian cookbooks by Denise Landis in the New York Times reminded me how vegetarian cooking had evolved, and continues to expand twenty years later.

Fake Meat?

I’ve had intermittent short meatless stints during my adult omnivore life. I have substituted chicken or pork (‘the other white meat’) for beef, without any agenda, or rationale. My vegetarian leanings have been marginal, my knowledge of veganism, short on detail. While respecting adherents to these diets, and interested in the purported health claims made by proponents, I’ve held no fast ethical, ecological, or political view on the topic of meat.

My own view of plant-based meat substitutes and news of breakthroughs in lab-grown meat alternatives was simple avoidance. It sounded suspect, and the idea of mimicking something I already felt conflicted about, was frankly unappealing. The book calls out the Impossible Burgers by name, and makes a compelling case for the falsity of the whole industry.

Kennedy describes Fake Meat it as a plant-based food product with a capitalist growth model. The same unjust food structures are being mapped onto a plant-based approach.

Unknown content block type: FlexiblePageTemplateFlexibleContentPhotoFullWidthLayout

{

"__typename": "FlexiblePageTemplateFlexibleContentPhotoFullWidthLayout"

}Vegan Cheese?

So, my gut reaction (bad pun) to fake meat was unexpectedly validated. Kennedy is firm in her critique, but makes clear that a decision to eat no meat, or less meat, is nuanced and multi-faceted. The way the book describes attitudes toward vegetarians and vegans was spot-on. The topic of dairy and plant-based cheese is also examined closely. I have often dismissed plant-based cheeses as vegan fanaticism, and the products I have sampled as poor imitations of “the real thing.’ When reading about the experiments in cheesemaking by dedicated craft producers, I came to see that the commercial plant-based cheese substitutes were no more like cheese than Velveeta is like cheese. And unlike making a burger to appear like bloody flesh, cheese is defined by the process.

The Pioneers

From hippies, to punks, to tech bros, she presents a progression from a counter-culture movement to an elitist adventure. There are many examples of restaurants leading the charge to make plant-based eating more mainstream, with inventive chefs introducing creative vegetarian cuisine to new audiences. From stories of surviving communal farms, eco-feminist collectives now shuttered, iconic restaurants to high-end fine dining establishments, Alicia Kennedy compares and contrasts, with facts and opinion, with thought-provoking narrative. For me, highlights were reading about the trendsetters with whom I have been familiar, such as Mollie Katzen and Amanda Cohen along with so much historical information that was new to me.

If you are a die-hard carnivore, or vegan-skeptic, you might want to read this book to understand another culinary perspective, by an author who is obviously enjoys food.

I didn’t to read this book to change my diet.

But it has changed.

For any home cook who loves variety, embraces simplicity, eschews processed shortcuts, the message of the book is in the title. For healthy, flavorful meals, there is “no meat required.” Eliminating, or limiting it, without replacing it with commercially produced substitutes (with dubious claims to improving quality of life) has many social and ecological benefits. It can be a challenge to break old habits, and it’s often easier to think of meat as the main course with sides in planning a meal. Serving a delicious, colorful plate of grains and vegetables with intentionality takes a bit more planning, but it is creatively deeply satisfying.

The change is subtle, but I have been influenced to reconsider what is at the center of plates I prepare, and proteins I choose to eat as “add-ins.” Kennedy argues that in addition to removing meat from our plates, ingredients should support local food systems. It is difficult not to respect that. ![]()