From Texas to Minnesota, A Forager on the Road

“Eyes on the road, Dad.”

“What makes you think they weren’t?” I reply to my 13-year old daughter.

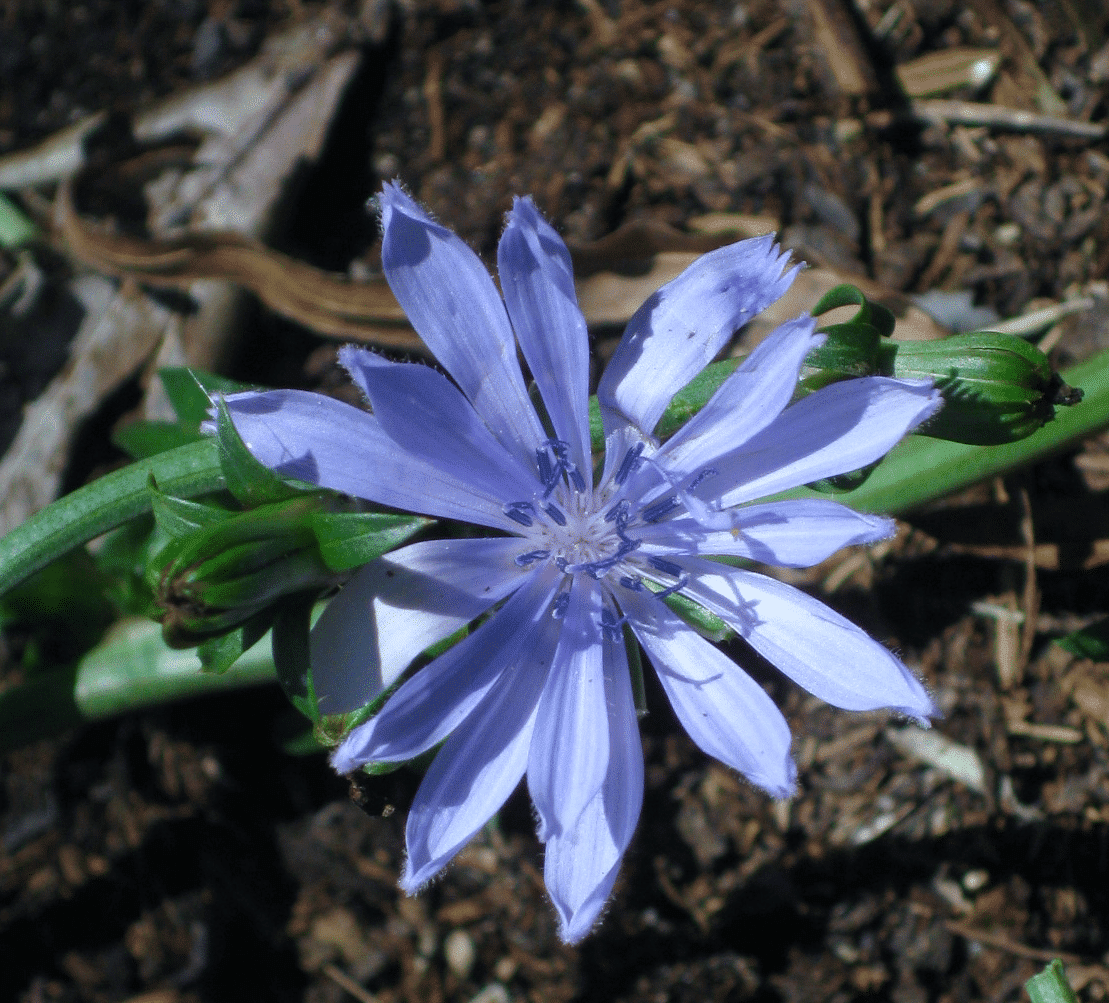

“I saw the chicory and figured you’d be staring at it, too. You love that plant,” is her answer. “You look at plants too much!” pipes up my other daughter, a 10-year-old who’s constantly looking for ways to correct me.

The United States is a place of defined regions, each with very specific cultures, foods, and accents, but our obsession with getting from point A to point B as fast as possible is blurring everything into blandness. A roadside McDonalds in Louisiana prides itself on offering exactly the same taste and appearance as one in Colorado. It takes time and effort to find the glorious barbecues and pies of the south, the fine steaks of the west, the amazing seafood creations of the east coast, the hearty home cooking of the Midwest. But point B beckons and diversity loses to speed.

“Eyes on the road, Dad!” says my daughter again, 30 miles down the road. “We’ve been seeing those wild carrots for an hour.”

“Yes, but did you notice the water hemlock among this clump? It’s super-poisonous,” I answer.

Every July I drive my family 1200 miles from our home in Texas back to Minnesota where I was born. I-35 covers 992 of those miles, passing through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, and Minnesota as a seemingly homogenous ribbon. To me, a forager, the view outside my windshield isn’t an unremarkable sea of

green but a rich tapestry vibrantly displaying the different regions. A distinct progression of edible plants passes by, each with a specific history of use in the regions they appear.

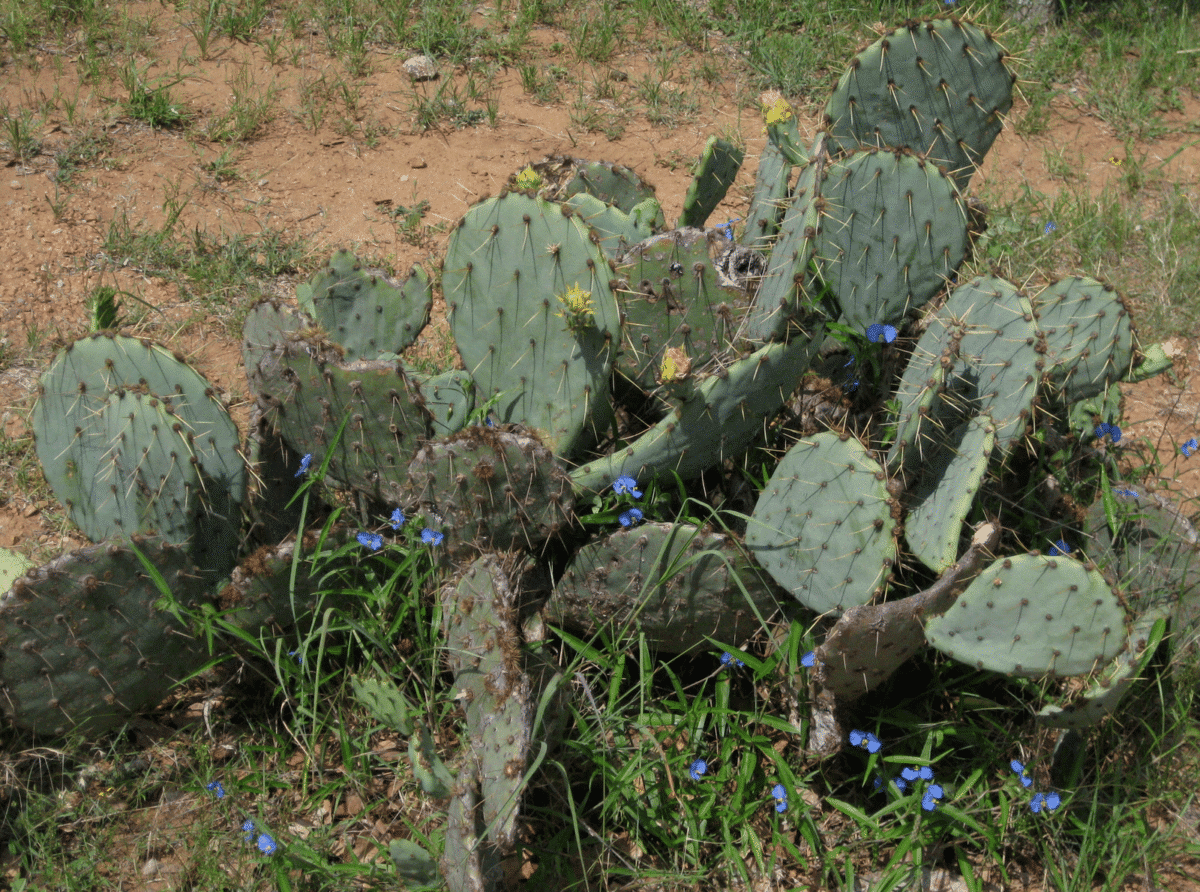

Crossing Texas, clusters of prickly pear cactus dot the roadside underneath yellow blossoms of wild sunflowers. Thin slices of prickly pear cactus pad are a unique substitute for green beans, and sunflower petals add bright sunshine to salads, soups, and tea. In a dry, hot land one must fully embrace the sun to handle it.

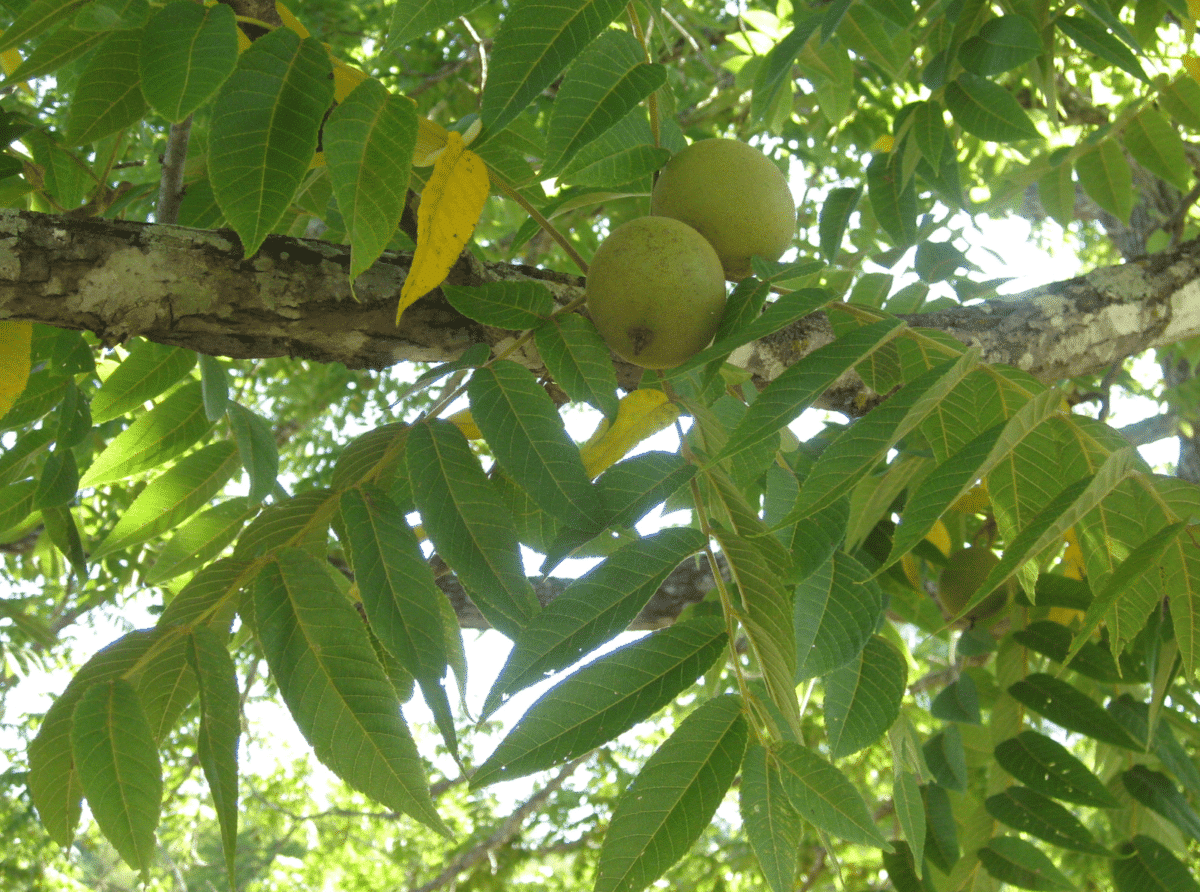

After many hours we approach Red River, near the boundary between Texas and Oklahoma. Magnificent black walnut trees appear on the Texas side, several miles from the river. After crossing into Oklahoma these trees gradually fade away. Black walnuts will reappear as we approach major rivers on our northward travel, allowing me to track our progress not by towns and cities, but by nature.

“It’s already too late to gather baby walnuts for pickling, right?” asks my older daughter, who shares my love of foraging.

“Yes, that needs to be done in June,” I say.

“Yeah, everybody knows that!” jabs the 10-year- old, looking to add “excitement” to the drive.

If it were fall, the branches would be pulled down under the weight of lime-sized nuts. Cracking them open is a chore but worth doing for the rich, aromatic meat inside.

Oklahoma’s bluffs flatten to grasslands and stands of wild carrots appear. Also known as Queen Anne’s Lace, these slender, regal plants topped with white crowns are unmistakable. Ancestor of the modern carrot, their taproots are white and woody but have the “carroty” flavor of their modern, orange descendants. Due to their toughness, wild carrots are best used as a flavoring agent for soups and stews but removed before serving the dish.

If cottonwood trees are nearby one must use caution when harvesting wild carrots. Cottonwoods signal water and that indicates that deadly hemlock, a dangerous, water-loving mimic to wild carrots, may be present. However, with a little bit of study the differences between safe wild carrots and deadly hemlock will leap out at you.

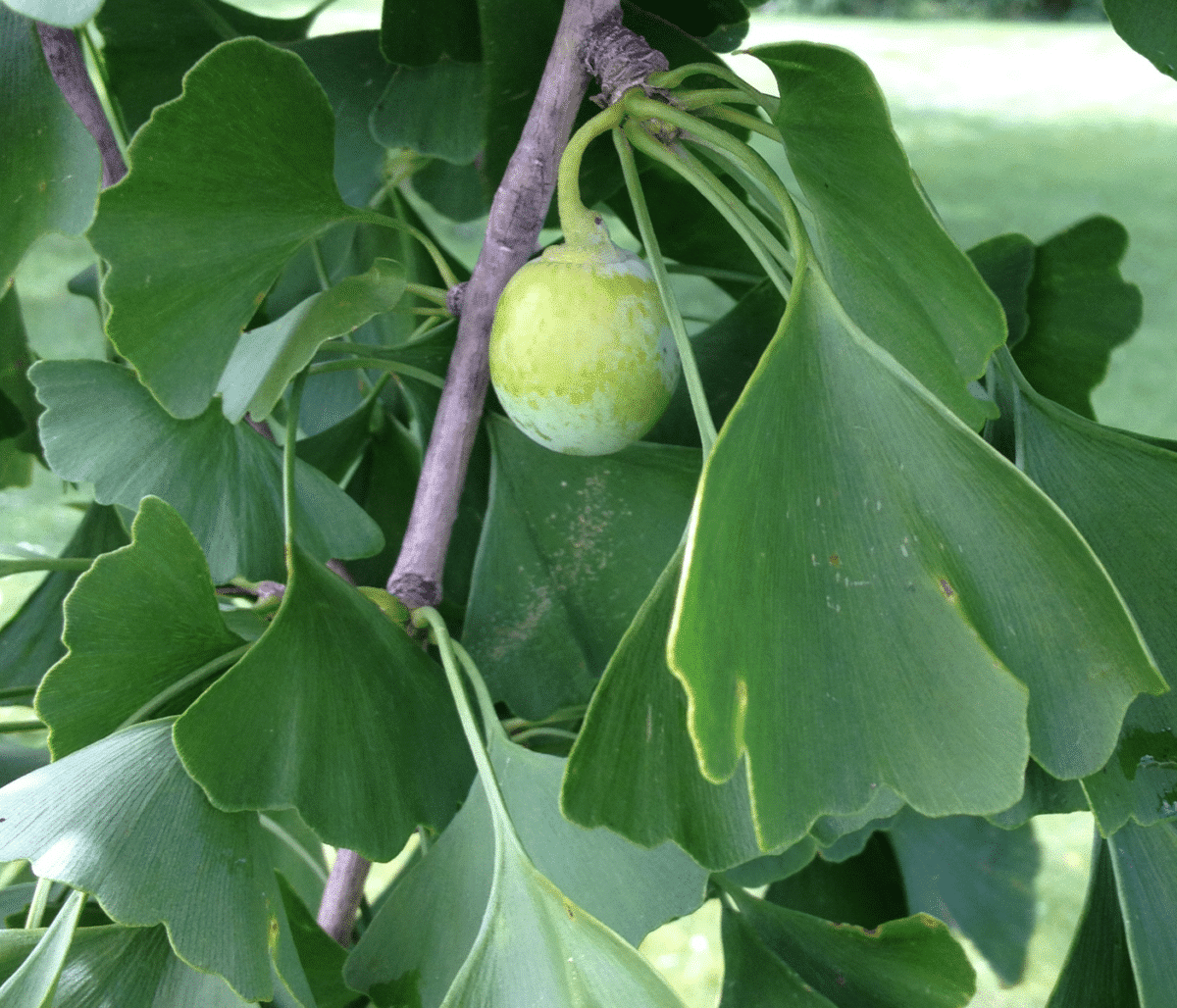

In Kansas we stop for a bit to stretch. This rest area is sheltered from the hard prairie wind by a ring of trees. As the girls run around burning off energy, a particular tree catches my eye. Beyond the elms, hackberries, and hickories, it stands with small, fan-shaped leaves fluttering in the wind. Many green fruit hang from its branches. Can it be…? Holy cow, it is!! Here in the middle of nowhere someone planted a ginkgo tree! This prehistoric Chinese tree has found a niche in east and west coast landscaping but is somewhat rare elsewhere.

Ginkgoes are planted by those who know the secrets of hidden food, signaling to me there’s a fellow forager working for the bureaucracy of Kansas’s DOT. Does he or she plan to harvest the nuts inside this ginkgo’s fruit?

More intriguing, what other treats have been hidden in plain view along the Kansas stretch of I-35? Turning to the windbreak trees, I notice an unusual abundance of native hickories. Beneath them, dandelions and wild violets run wild, suggesting this roadside rest isn’t sprayed with herbicides. I smile at the secret feast.

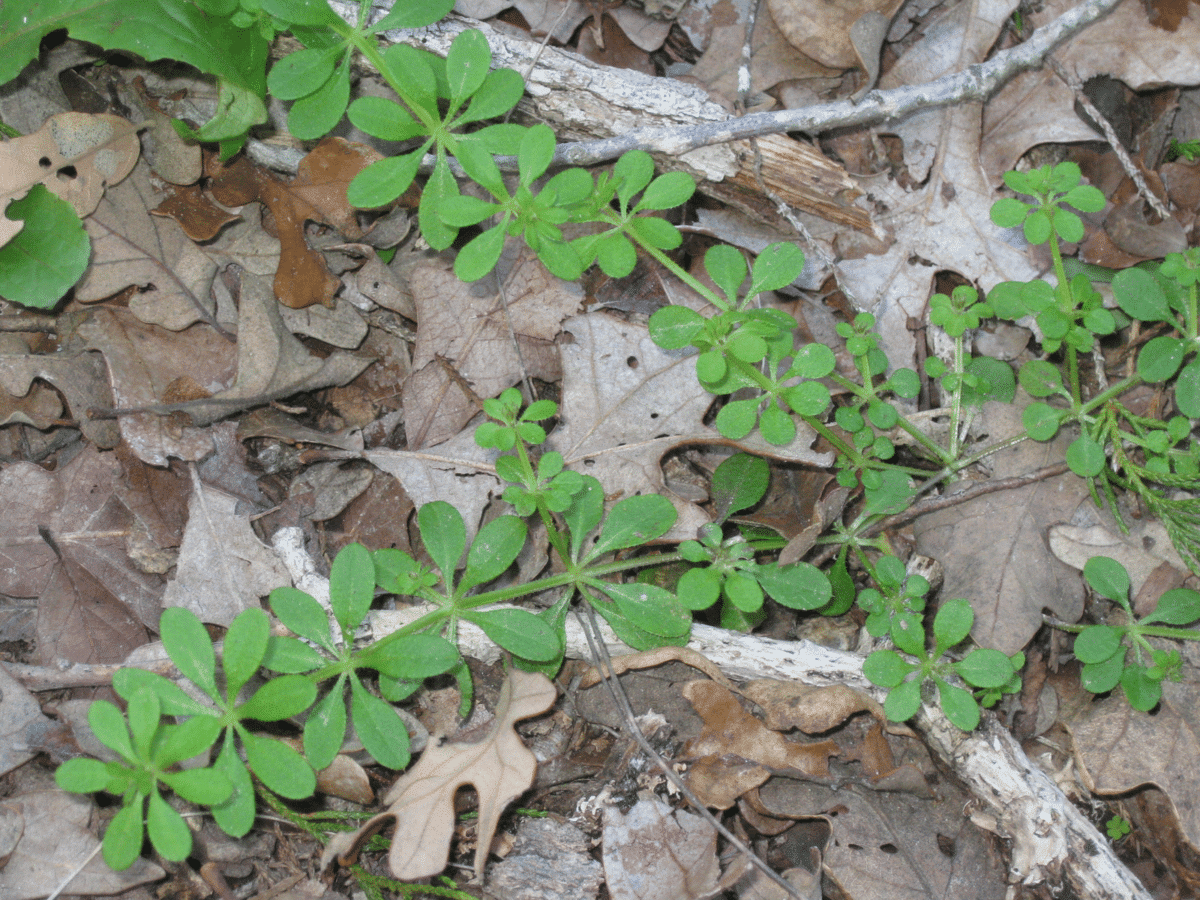

Farther north now, and there’s a dramatic change to the plants. At roadside rest areas cleavers appear, from which a tea rich in vitamin C can be made. Cleavers’ presence signals the crossing of a line where southern wintertime plants switch to being northern summertime plants. Grocery stores have blinded us to the seasonality of foods but foragers must follow nature’s true rhythms. Being aware of the changes to these rhythms adds another dimension to the road trip, we’re not just traveling through space, but “plant-time” as well.

Chicory is another such “switched” plant. The purple-blue, dandelion-shaped flowers dot the rough roadsides of Kansas in July. In southern states this plant is found in the cool winter months, and its large taproot is prized for making a coffee-like beverage. As we travel north, chicory appears in great numbers but is used less and less by the locals. Why? Because northern states didn’t suffer blockades during the Civil War and so wild substitutes for their foods, drinks, and medicines weren’t needed. Botany and history are intertwined along the interstate freeways!

We enter Missouri on the second day of the trip. A red sunrise shines through early morning ground fog swirling among the fractal trunks of sumac.

These small trees stand in clusters, arms raised up, silently watching traffic pass. The single trunk splits in two halfway to the tree’s top. Then halfway up these two branches split and halfway up the splitting again happens. The splitting occurs over and over with mathematical precision to produce patterns normally only seen in scientific journals and head shop posters. Here in July the branches end in pyramidal spikes of small, cream-colored flowers buzzing with bees. By summer’s end those flowers will have been replaced by tiny, red berries whose surfaces are covered with a tart/tangy powder. Stirring the berries into water results in a spectacular-flavored “sumac-ade.” Even better is to dry these native berries, then grind them into a seasoning powder that gives a Mediterranean/Middle Eastern zing to lamb, chicken, and fish dishes.

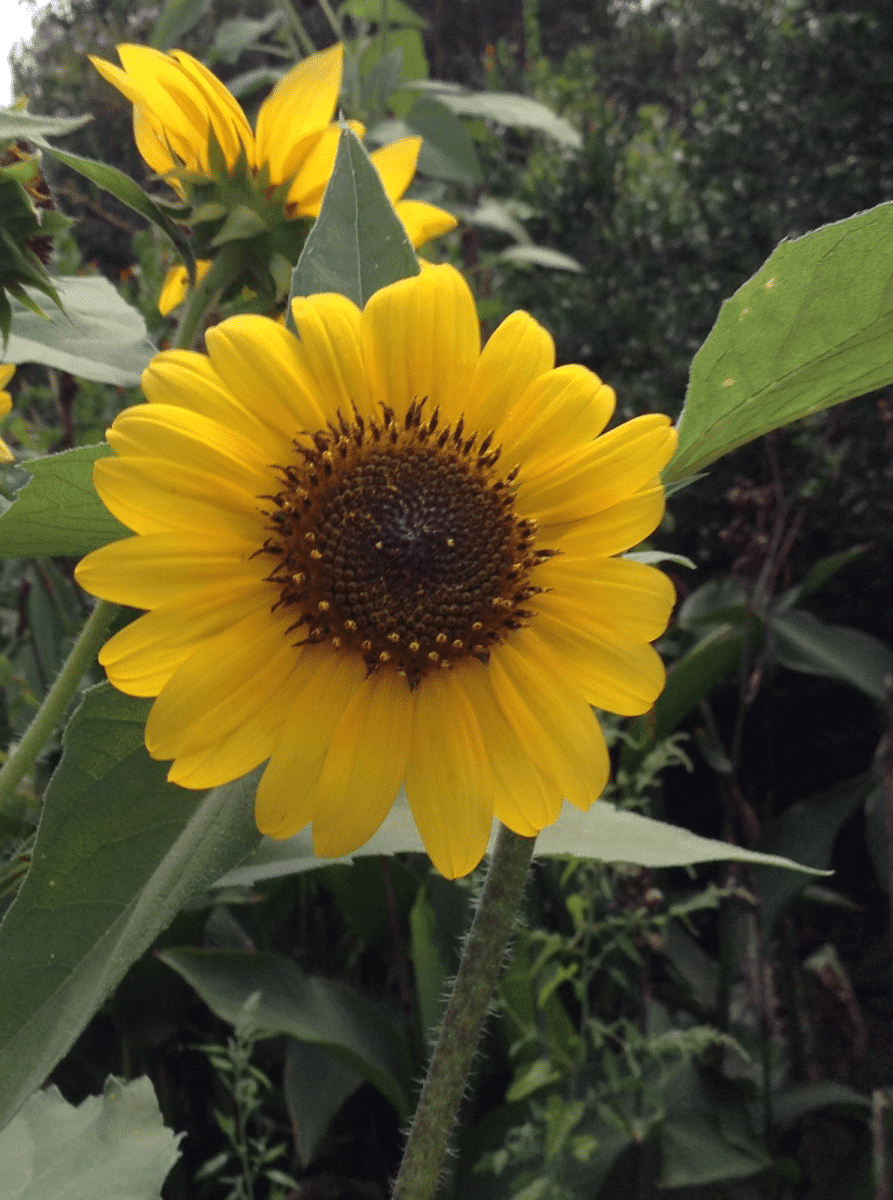

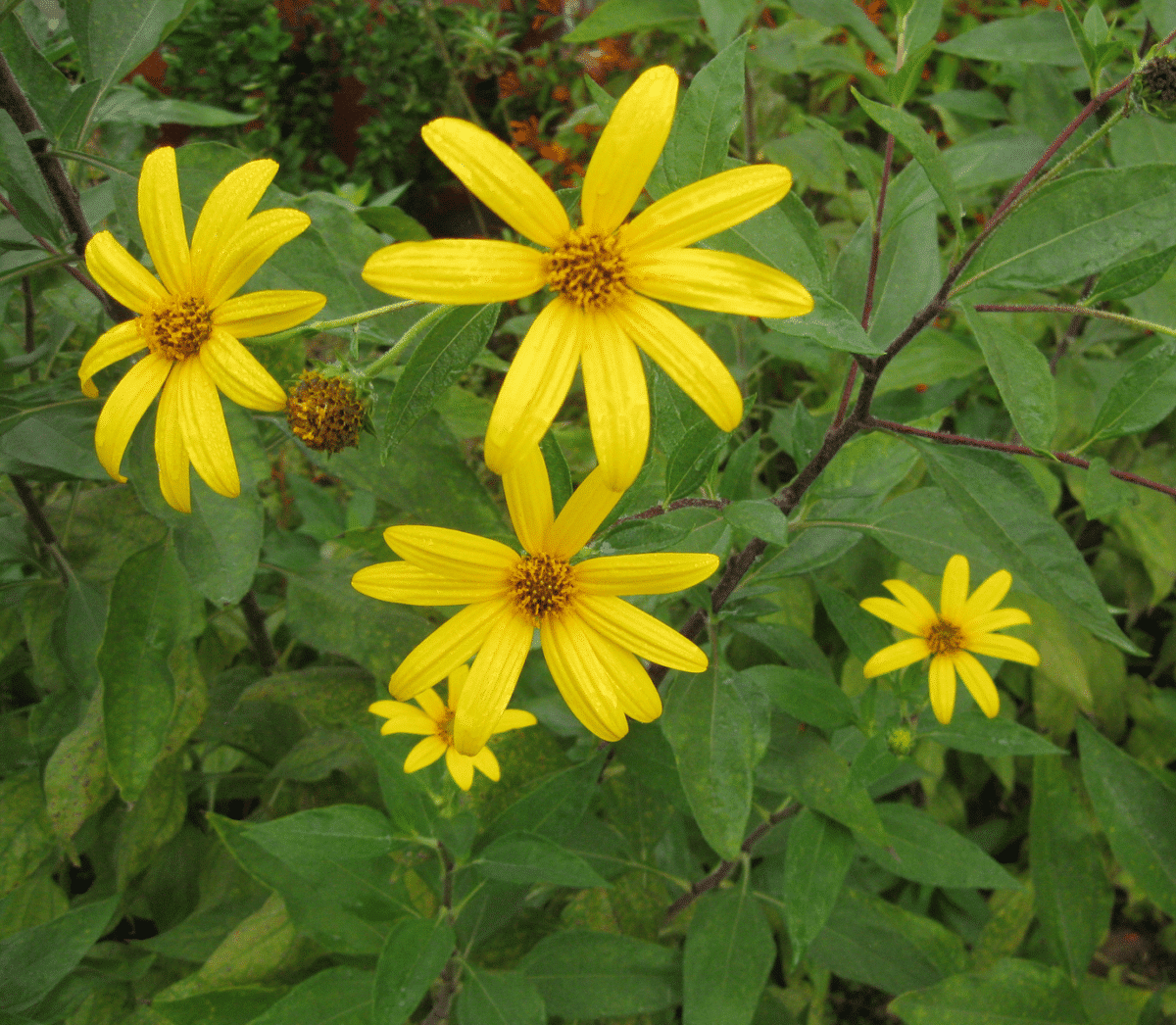

Miles of cornfields and wind farms indicate Iowa is rolling by. Reappearing along the edges of the irrigation canals seem to be the same wild sunflowers seen in Texas. I notice that the center of these sunflowers is yellow, while the center of the Texas ones were dark brown. Though in the same biological family, these Iowa sunflowers are Jerusalem artichokes. I yearn to collect their nut/potato-flavored tubers, but they won’t be ready for harvesting until fall. Since ancient times field mice have had a fondness for these tubers, digging them up and stashing them in hollow trees, only to lose them to the local Native Americans who had secretly been watching. After thousands of years the mice still haven’t learned to hide the tubers better.

We cross into Minnesota. The effects of the last ice age are still visible, ancient glaciers having created a landscape of lakes, rivers, and streams. In a sluggish, unnamed Minnesota stream, the large, arrowhead-shape leaves of wapato thrust up from the water. The young, tender leaves are cooked in a manner similar to the collard greens of down South. However, their real treat is the wapato tubers hidden in the mucky river bottom. Squishing around in the mud, toes learn to find and pluck the golf ball sized tubers, best prepared by roasting under a campfire, as has been done for millennia.

We pull up to the 130+ year old farmhouse where I grew up. The low sun illuminates a stand of sugar maples that my dad has been tapping for decades. Many a cold, late-winter day was spent standing outside, carefully boiling the sap down into thick, sweet syrup. This memory is interrupted by a swarm of kin pouring out of the house and engulfing my far-traveling family and me. With them comes the scent of my favorite dinner, prepared by my mom for our arrival, and containing local wild greens she taught me to harvest so many years ago. Our journey over, we enter the house. The 10-year-old, with a sleepy voice says, “Good drive, Dad.” ![]()