Every Tuesday, when it would be my parents’ turn to work the closing shift of their restaurant, my newly-licensed brother would drive my sister and me over to a little strip mall for dinner.

I liked my pho plain – rice noodles, broth and a couple of meatballs. Not even shaved onions or scallions were allowed or I would throw a fit. Both of my siblings would always sneer at my untainted soup as they squeezed wedges of lime and bottles of sriracha into their own broths with a pompous, sophisticated flair. At family meals my dad would try to sneak bean sprouts, squirts of fish sauce, and perilla leaves into my bowl, attempting to convince me of the wonders of a customized bowl of pho.

“Just leave him be!” my mother would snap in her spitfire Vietnamese, and everyone would back off – I was always the mama’s boy. Scars and burns criss-crossed her forearms from running the back of the house, something that I would come to share many years later when I began working in a professional kitchen. Once, indignant and embarrassed, I squirted a smiling face of sriracha on top of a ramekin of hoisin then used one of my chopsticks to swirl it into abstract art. I dunked a bit of meatball into it, chewing it for a second before spitting it out, my tongue a fiery mess as everyone laughed.

Pho made up our livelihood, supporting us in both a literal and emotional sense. Like it or not, to us kids it was a constant reminder of who we were and the country my parents left. At school, our classmates were always excited when we said our family had an Asian restaurant because they thought we ate orange chicken and fried rice everyday, not bowls of noodle soup with tripe and tendon. My parents, in response to my siblings and I trying to become more “American” and detaching ourselves from their culture, made us spend weekends drying chopsticks and manning the cash register using our broken Vietnamese. The register itself never worked, so calculating change mentally was their version of extracurricular math tutoring.

It still amazes me to this day that the thousands of bowls of pho they’ve made for me in my lifetime have all tasted exactly the same. There’s something to be said about having consistency in an ever-evolving life: I would have never guessed that one day my sister would move to New York City, that I’d move four hours away to go to school, or that we’d eventually be closing the doors of the restaurant. Any time I made the long drive home from school, even if it was at three in the morning, there would always be the ingredients for a bowl of pho waiting to be prepared.

Mom would awaken from her slumber – her hair now gray – to boil a pot of water in which to blanch the rice noodles. She would then pour the scalding, aromatic broth over them, even though we both knew I was perfectly capable of doing it myself. I was never officially home until I breathed in the smell of broth made from beef bones.

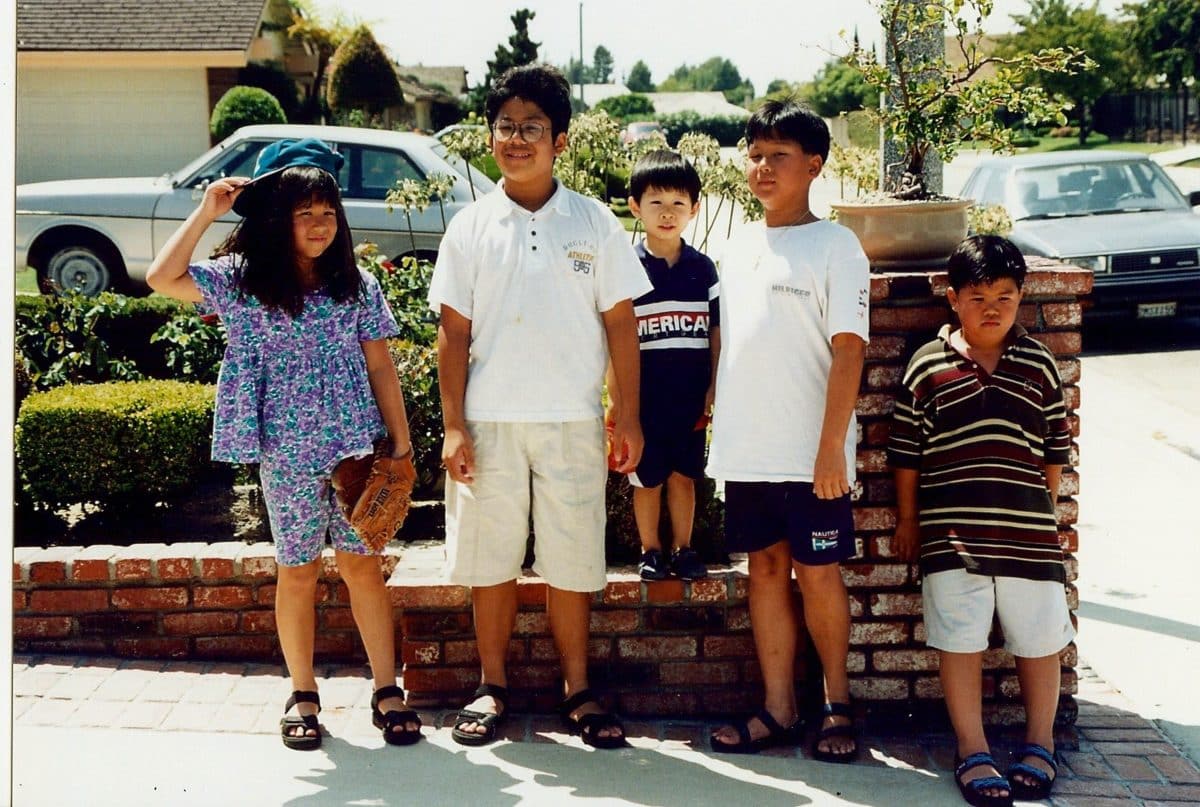

My bowl has grown up with me through the years. There’s now a raft of brisket floating on top, a scatter of Thai basil and culantro, and the broth is tinted slightly rouge with chili sauce. But with each bowl I’m transported back to a little strip mall with shiny red tables and harsh fluorescent lighting, a time when Vietnamese noodle soup had yet to become a hackneyed trend made up of a bunch of un-pho-nny puns. I’m still nine, and having all five of us around the table hasn’t become an uncommon, special occasion yet. My parents don’t have grey hair and are still sprightly, and I’m still oblivious to how hard they worked to stay that way in spite of the heartaches and struggles they fled from all those years ago. Mom is sitting at the table laughing and making fun of how I can’t use chopsticks, while Dad is behind the cash register pouring himself yet another Vietnamese iced coffee and snacking from his hidden stash of American donuts. Everything is the same as I remember, just like the bowls of pho. ![]()