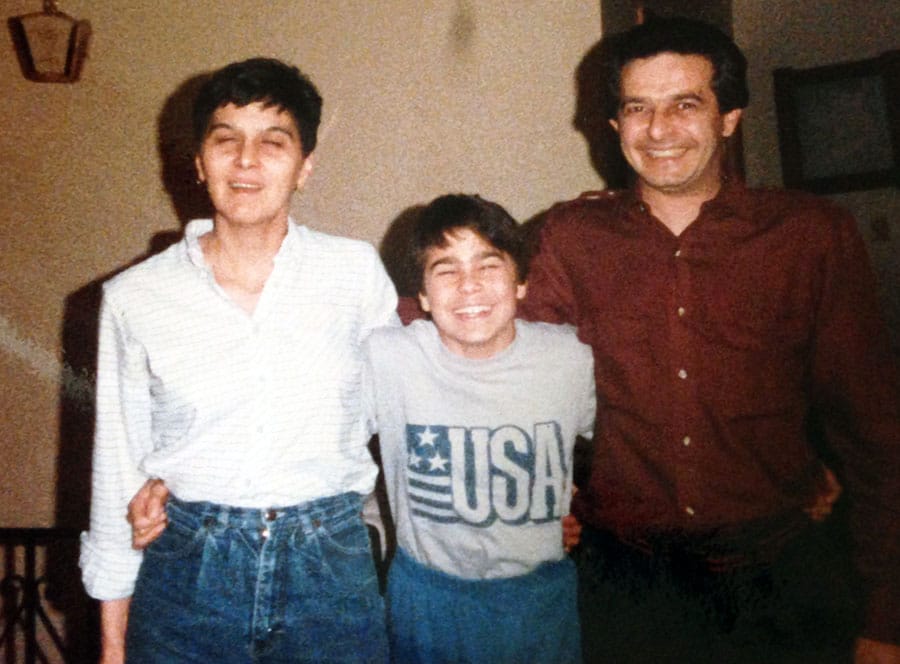

In my family, Sundays meant eating a big Italian meal at my grandmother’s house every week.

My father had a close relationship with his parents and wanted to spend Sunday afternoons with them. The only exceptions were if we had a church or social event scheduled. I would have preferred spending Sundays going to football games or out to the movies with Dad. As the week progressed, my sister, Lisa, and I would dread the ritual of visiting our grandmother.

Every Sunday Amelia would meet us in the driveway when we arrived at her small brick ranch house in Rome, New York, sauntering toward the car while wiping her hands on her apron. She was a small, sturdy Italian-American woman with strong, rough hands and reddish-brown hair, and she would squeeze each of us as we piled out of the car. It was as if we had traveled across the country to visit her or hadn’t seen her in years.

My mother never tried to hide the fact she hated going to Amelia’s house. Often Mom would feign illness or just refuse to come with us. “I don’t feel well, I’m not going,” she would say, sometimes waiting until we were ready to leave the house before breaking the news to my father. She would then retreat to her room and lie in bed.

Dad would head upstairs and walk into the room. We followed him up the staircase, stopping halfway so we could overhear their conversation. Dad would try to coax Mom to come along, but she would answer him curtly and he would get annoyed. “You’re impossible, you know that?” he would say. “I can’t win with you.”

My mother never tried to hide the fact she hated going to Amelia’s house. Often Mom would feign illness or just refuse to come with us. “I don’t feel well, I’m not going,” she would say, sometimes waiting until we were ready to leave the house before breaking the news to my father. She would then retreat to her room and lie in bed.

Dad would head upstairs and walk into the room. We followed him up the staircase, stopping halfway so we could overhear their conversation. Dad would try to coax Mom to come along, but she would answer him curtly and he would get annoyed. “You’re impossible, you know that?” he would say. “I can’t win with you.”

We would scurry down the stairs and sit on the couch in the living room as we waited for our father. A few moments later Dad would come downstairs, crestfallen, and announce, “OK we’re going without her.” And we knew well enough not to ask him if we could stay home too.

My father’s attachment to his parents, which my mother considered unhealthy, strained Mom and Dad’s relationship, contributing to their eventual split. Mom belittled him about it, telling him to stop being a “momma’s boy” and “be a man.” After his father, Fernando, — nicknamed “Ferdie” — died, Dad spent more time with Grandma, apparently driven by a son’s obligation to take care of his mother. Privately I always considered the situation reversed. My grandmother protected and watched over my father, giving him money when he needed it — when his bills overwhelmed him or his gambling debts soared.

I also realized that my father’s childhood illness had motivated Amelia to cosset him for the rest of his life. Dad had been born with a hole in the heart, leading to stunted growth and deteriorating health. In 1959, when Dad was sixteen years old, pioneering surgeon C. Walton Lillehei — the “father of open-heart surgery” — repaired the ventricular septal defect in a lengthy operation at the University of Minnesota. Afterward, Amelia couldn’t stop herself from being overly protective of my father.

I don’t mean to imply we didn’t love our grandmother just because we didn’t like going to her house every Sunday. We knew that she cared deeply for us, but the elaborate spread of food and her constant doting irritated us. And we resented the obligation imposed on us by our father.

The Sunday meal at Grandma’s was never a relaxing family dinner; it was closer to a theatrical presentation. The menu usually consisted of antipasto, homemade macaroni with red sauce (cooked with sausage, meatballs, and pork ribs), breaded chicken cutlets, and fresh Italian bread from a local bakery. With fine china, the best silverware and pink cloth napkins, Amelia seemed to be preparing for special guests every week who never came. Our small family was the only one seated around the table, although periodically my Uncle Charles, his wife, Cathy, and his two children, my cousins Jeff and Lauren, would drive in from Syracuse to spend the afternoon with us.

Amelia spent those Sundays serving us large quantities of food and smothering us with affection, as if trying to prove her love was authentic. Every week she would say, “Listen, anything you kids want, anything at all, you just tell me. Hey, remember, you’re home here. This is your house too.”

As for her cooking, her spaghetti sauce and meatballs were as bland as tomato soup and meatloaf from a frozen packaged dinner. But we could blame our father, in part, for the lack of flavor in her dishes. He loathed garlic and suffered from Crohn’s disease, which meant his stomach couldn’t handle spicy foods. He also had high blood pressure, so salt was out too. “I have to cook this way,” Grandma would say, like admitting she did something wrong. “Your father can’t tolerate spices and with his high blood pressure, he can’t have the salt. But you can always add it later.”

I would get annoyed at her comments about her baked chicken breast, which I enjoyed eating. When I was about four years old, I had eaten a piece of her breaded chicken cutlet and Dad asked me if I liked it. I said, “Sure, it’s nice and greasy.” I had meant “juicy.” And so nearly every Sunday she would cook the same style of chicken — if she weren’t making a roast — and as she pulled the breasts out of the oven, she would look at me, smile, and say, “Grandma made her famous greasy chicken just for you.”

Each Sunday Dad would race around the kitchen, helping Grandma prepare the food for the meal. The house was built in 1959 and the cramped kitchen had never been modernized. It had cracked red laminate covering the countertops, a small range on one side, and an oven on the opposite wall. And as Dad strained the homemade macaroni in the sink or took the chicken or roast out of the oven, he and Grandma would get in each other’s way as they rushed to get the serving dishes on the table. They raised their voices as they argued about some task or aspect of the meal. I can remember my father saying things like: “Will you just get out of the way and let me do it? Don’t worry about it, I’ll take care of it. Amelia, would you stop?”

Finally we would be called to the dining room, which was an addition to the main house and had poor insulation. The windows looked out on the backyard and the draft from the windows chilled our backs when we sat against the outside wall. The only time the room wasn’t cold was in the middle of summer. But Grandma would have a space heater running continuously and I liked the steady, comforting sound it emitted.

After we finished dinner Amelia and Dad would clear the dishes, wash the pots and pans, and store the leftovers in the fridge. Then Amelia would put on the coffee and bring out dessert. Sometimes it would be an apple or lemon meringue pie. Other times it would be biscotti, cannoli, or pasticiotti (pronounced pasta-ch-ought). “You kids take as much as you want. I made it [or bought it] just for you,” Grandma would say. But even after the adults had taken their time eating dessert, smoking cigarettes, and drinking coffee, we still couldn’t leave. My father wanted the visit to last for at least two or three hours.

When the weather was nice, Lisa and I would head outside to walk around the neighborhood or explore the backyard. It was a rural area, so there were trees, rabbits, birds, and even a few deer to draw our interest. But in winter, when it was too cold to go outside and build snowmen or throw snowballs, we would be cooped in the house. The only option for amusement then would be going into the living room, sitting on the rust-colored couch, which Amelia called a “davenport,” and playing cards or watching TV.

I remember the clock on the living room wall ticking as the Sunday afternoons dragged on, and I recall the smell of Grandma’s baby powder redolent in the nearby bathroom and in the hallway covered with worn, beige carpet. Sometimes I would lie down on the couch the opposite way, with my legs elevated on the back support and my neck and head hanging off the edge of the seat. I would stare at the ceiling for several minutes, pretending I could walk across it. After a while, the perspective in the room shifted and I would lose all sense of time and place. I drifted away staring at the eggshell ceiling and the angles in the corners of the living room. This made the time pass and I would forget I was still stuck at Grandma’s house.

When Dad announced it was time for us to go home, Lisa and I would hurry to put on our coats. Before we would leave the house, though, Amelia would pull us into the hallway, open her clenched fist, and slip us money. The crisp, green bills were always folded in a tight strip and Grandma’s furtive behavior made it seem like we were participating in a drug deal. But in fact she was just being generous and didn’t want Mom and Dad to see her giving us money, so as not to make them feel bad or think she was imposing in some way.

“No Grandma, we don’t want it,” we would say. We would attempt to give it back, but Amelia would push us away or thrust the bills back into our hands. “You take it,” she would say. “You go and buy yourself a hamburger or a treat.”

And then she would hug us and repeat: “You come up anytime. Hey, remember, this is your home here.” ![]()