Jordon Almonds were always present at at Italian (and Greek) weddings. They were thought to have aphrodisiacal potential.

Something to get things off to a good start. Seems like a lot to ask from an innocent looking sweet. Next to every dinner plate were small white mesh bags tied with white ribbon with a few usually white or ivory colored candies nestled inside.

As children we’d snatch unattended bags so that we had a bulging pocketful to take home. Because of their gentle colors and egg shape, they would also turn up in Easter baskets in with the mini-chocolate eggs, bunnies and dyed eggs on a bedding of brightly colored excelsior that bore little resemblance to the curling strips of wood from where it takes its name.

Jordan Almonds were more appealing for their pastel sugar coatings than their taste. We sucked on the hard sugar shell until we reached the tan colored nut that by then was damp and had lost its snap. While they were not as satisfying as a more conventional candy, nonetheless we ate a generous handful before growing bored.

If anyone had known why they were called Jordan Almonds, they weren’t sharing.

Like so much that was part of our Italian ethnic traditions — it just was. No explanations. They were just jordanalmonds, one word. Who knew then where Jordan was, or that almond trees thrived on the Jordan River banks?

As children, how were we to know that the five candies were color-coded (pink, pale blue, yellow, green and white), and each had a symbolic value — happiness, health, wealth, fertility, and longevity. No one explained their significance, and none of us would have thought to ask. Furthermore, the so-called bitter almond was meant to contrast with the sugar coating; embodying the paradox of the bitterness of life (so dear to my Sicilian relatives) and the sweetness of love (ambiguous at best.)

For an added touch of gaiety, Jordan Almonds and cannellini ricci, (sticks of cinnamon bark encrusted with sugar in colors like Jordan Almonds), were often scattered amongst the cookies from our local Italian bakery.

The origin of sugared almonds may, however, be as old as ancient Rome.

A confectioner known as Julius Dragatus supplied his signature, sugar encased almonds to be served at weddings and births by the aristocratic and the wealthy for their symbolism and rarity. So associated did these become with Julius that they eventually were known as dragati. Not far from dragati to dragée.

Dragées

Much later I learned that the name may have been a corruption of the French jardin, as in garden grown or cultivated, as opposed to the less palatable wild almonds. The French, however, call them dragées (drazh-AY) a term with which I became familiar only after becoming a chef. In a strange möbius strip of elusive etymology, it is also thought that Jordan perhaps was a corruption of Verdun, the northeastern city in France that was known for sugar-coated medicinals that became known as dragées de Verdun. Verdun … Jor-dun. A stretch, but possible.

M&Ms

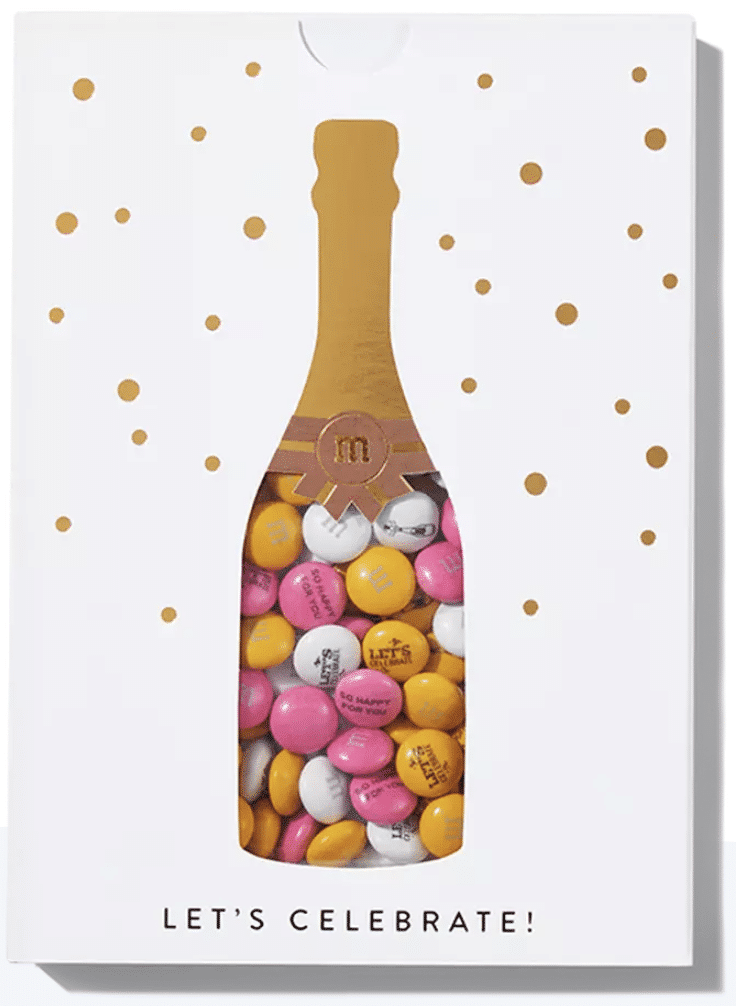

While M&Ms may have a slightly less distinguished history, can the ubiquitous melt-in-your-mouth candy qualify as dragées? And if a true dragée, might it rise to an occasion such as Easter? Find its way into little mesh gift bags? After all, when first manufactured during the Second World War, M&M’s, like Jordan Almonds, were originally offered in five colors — red, yellow, green, violet and brown. While not, as far as I know, freighted with symbolic values, the green were said by some to be an aphrodisiac.

Today, M&M’s are available in at least 17 colors (including pastels), can have an almond (introduced in 1988), and can even be customized for special events like, you know, Easter and weddings.![]()

For an added touch of gaiety, Jordan Almonds and cannellini ricci, (sticks of cinnamon bark encrusted with sugar in colors like Jordan Almonds), were often scattered amongst the cookies from our local Italian bakery.