The future of farming is no more just outdoors, but indoor and vertical. The vertical farming concept took birth in 1999 as an idea in Dr. Dickson Despommier’s class on medical ecology at Columbia University. Despommier defines a vertical farm as any building which grows food inside of it and is taller than a single story. Employing closed-loop agricultural technology, all the water and nutrients are recycled and the only thing that actually leaves the building is the produce.

Jack Ng started one of the world’s first commercial vertical farms in Singapore. Known as Sky Greens, this vertical farm makes use of a patented technology called ‘A-Go-Gro’ to grow lettuce, spinach and many other leafy greens. In this system, vegetables grow on 9-meter (30 feet) tall A-shaped towers, each hosting thirty-eight tiers of growing troughs. The troughs rotate around the aluminum tower at a speed of one millimeter per second, which ensures uniform distribution of sunlight, proper air circulation and irrigation for all plants.

The concept of vertical farming did not arise as a fanciful way of growing food, but as a practical solution to meet the impending food crisis facing humanity. Out of the present 7 billion world population, 50 percent of them are living in cities, and it is estimated that by the year 2050, the human population will reach 10 billion with more than 80 percent living in urban centers. As of now, 80 percent of the earth’s land suitable for farming is already in use, and this land mass will not be sufficient to meet humanity’s food needs in the next 35 years.

Looking at these statistics, the need of the hour is an efficient local food growing system that has low demands of energy and water, is not susceptible to climatic changes, and occupies less land space than traditional farms. Vertical farming fits these expectations, and many entrepreneurs and innovators around the world have successfully converted this concept into reality.

Food is now being grown in such unlikely places as old factories, abandoned warehouses, and industrial buildings. Technological advances in vertical farming methods and indoor lighting are enabling food to be grown alongside commercial structures and residences, making local food available for city dwellers.

Powered by a unique gravity-aided water-pulley system, each tower uses only one liter of water, which is collected in a rainwater-fed overhead reservoir. Costing $3 a month to run each tower, this hydraulic system has a very low carbon footprint, needing only the energy equivalent to illuminating a 40-watt light bulb. In accordance with the principles of “The Three Rs” — Reduce, Reuse and Recycle — the water powering the frames is recycled and filtered before circulated back to the plants, and all organic wastes are composted and reused.

Housed in translucent structures nearly four stories tall, the plants growing in a soil-based medium receive natural sunlight all year round. Producing one ton of vegetables every other day, the farm boasts a yield which is ten times more per unit land area than a conventional farm, while consuming less water, energy and natural resources.

While Sky Greens makes use of natural sunlight to grow vegetables in translucent structures, Green Spirit Farms in New Buffalo, Michigan, grows greens in a closed indoor facility under pink-tinted LEDs. In this vertical farm started by father and son duo Milan and Daniel Kluko, plants are raised on a soilless growing system called hydroponics, using mineral nutrient solution in water. With a growing cycle of just 21 days for most crops, Green Spirit Farms has seventeen harvests yearly, with a yield as much as 10 tons of lettuce in 500 square feet of space.

Compared to conventional induction lamps, Illumitex LEDs consume less energy and provide correct light intensity and spectrum. In addition, because of reduced heat and spread, LEDs allow less distance between plants and the light source, allowing more produce to be grown.

Daniel Kluko says the LEDs, providing the appropriate blue and red wavelengths for photosynthesis, have enabled power consumption to be reduced by 10 to 12% per system while increasing the yield by about 15 to 20%. This has helped to make the business more profitable and more sustainable.

Lead by Daniel, the research team in Green Spirit Farms is developing a smart phone/tablet app which will remotely monitor and control nutrient levels and soil pH balance, and even sound an alarm when a water pump is not functioning. This will give them the ability to look after multiple farms from afar.

Seventy-odd miles to the west of Green Spirit Farms is another vertical farm called FarmedHere in Bedford Park, Chicago. What was once an old corrugated-box facility has now been re-purposed into an urban farm. Just like Green Spirit Farms, this indoor vertical farm grows vegetables under the pink light of LEDs, but makes use of a food growing system called aquaponics, where plants and fish are grown together in one integrated system.

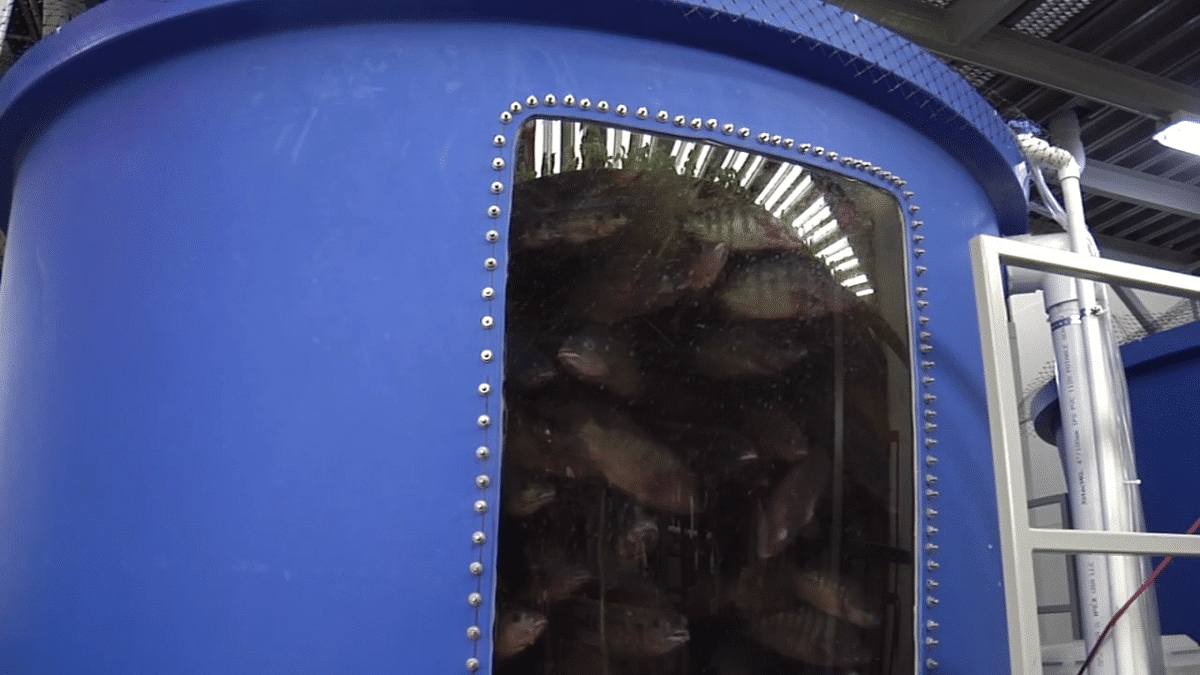

Tilapia fish, free of hormones, are grown in specialized tanks. The water with fish effluents — the source of nutrients for plant growth — is circulated among the plant beds. The plants, growing in a soil-less medium, absorb the nutrients and clean the water.

The water is then circulated back to the fish tanks, which keeps the tilapia flourishing. Both the fish and the greens are sold as food. This system, which grows 100% organic produce while generating no waste, has made FarmedHere the first USDA organic certified vertical indoor farm in the country.

With six layers of vertically stacked grow-beds covering an area of 90,000 square feet, the facility produces vegetables equivalent to that of a five-acre farm. With crops reaching maturity in about 30 days, half of what traditional farms experience, FarmedHere is able to meet the demands for salad greens, herbs, and decorative dressing, from seventy-nine grocery stores and vendors in and around Chicago.

Vertical farming is bringing fresh food to remote places that have been previously considered unsuitable for growing plants. Residents of the town of Jackson, Wyoming, beneath the snowcapped Tetons, no longer have to be dependent on food trucked from far-off Mexico and California. Instead, Vertical Harvest, a vertical farm now under construction, will soon be providing tomatoes, greens, and herbs year-round. Three stories high, the 13,500 square foot urban farm will produce an estimated 100,000 pounds of vegetables annually.

Along with the weather and climatic factors, circumstances arising from manmade disasters are also prompting entrepreneurs to start vertical farms. The nuclear disaster in Fukushima, in the wake of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, irradiated much of the region’s farmland, leaving many people doubting the safety of their country’s food supply. To meet the ensuing food shortage, Shigeharu Shimamura, a plant physiologist, converted an abandoned semiconductor factory into an indoor farm. And today, encouraged by the government, there are more than one hundred vertical farms in Japan.

Vertical farms are not just restricted to growing leafy greens for immediate human consumption. Caliber Biotherapeutics, a pharmaceutical company in Bryan, Texas, grows 2.2 million plants in structures 18 stories high. Lit with LEDs, this plant production platform with a growing area of 150,000 square feet is being used to make new drugs and vaccines. In addition to providing an ideal environment to closely monitor and control plant growth, this indoor closed facility provides a protective barrier against possible diseases and contamination from the outside world.

At present most vertical farms are limited to growing leafy vegetables like basil, micro-greens, lettuce, arugula, kale and spinach, though some have been successful in growing carrots, radishes, strawberries and peppers on a commercial scale. Further research is needed to find suitable techniques to grow staple crops like rice, wheat and maize, or tubers, like potatoes.

Mankind is at the doorstep of yet another green revolution. The strides made in vertical farming — from a classroom idea to a commercially viable technology — in the last fifteen years are quite remarkable, but are just the beginning of a new world in farming. ![]()