A History of Bees

The year 2021 marked the 90th anniversary of Champlain Valley Apiaries, a third-generation honey business owned and operated by the Mraz family in Middlebury, Vermont. This apiary and its history of bees was established by my father, Charles Mraz, in 1931. He was born in Queens, New York, in 1905 and became interested in beekeeping at a young age. In the early 1920s he spent summers in the Finger Lakes region of New York working for a commercial beekeeper. In 1928 he settled in Middlebury and began his own operation three years later. With 1,200 beehives, called colonies, it is now one of the largest apiaries in New England.

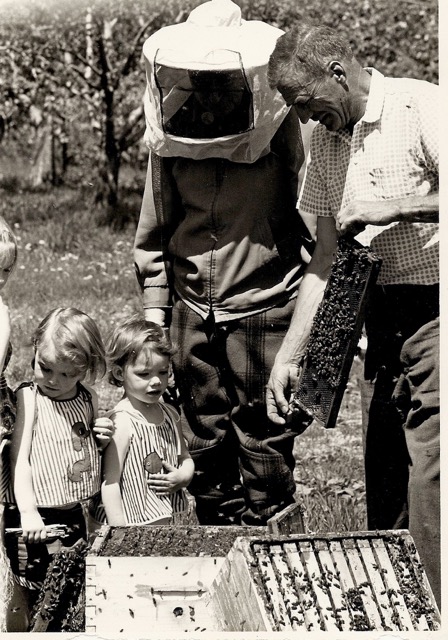

My brother, Bill, took over the business in the 1970s, though Charles was always on hand to help and stayed active until his death at the age of 94. Bill’s son, Charles “Chas” Mraz, took the helm in 2005, but Bill still helps in the beeyards, offering guidance and support as our father did for him.

I grew up around this history of bees and never gave beekeeping much thought or found it unusual. There were hives behind our house and bees and honey everywhere. I can still remember the family station wagon with its smell of beeswax, and dead bees all along the dashboard. When we turned on the defrost fan, the bees “flew” around. In the kitchen, we used honey to sweeten everything. Not only did my mother cook with it, she used it to dress our wounds. Unfortunately I didn’t learn to keep bees myself. Being of a certain generation, my dad had his sons carry on the work and history of beekeeping, while my sisters and I worked in the honey shop labeling jars and filling them with honey.

People are often curious about how honey is collected and packaged. Mraz honey comes straight from the hive and is minimally processed, without heat or filtration.

Production

The boxes that make up the hive, called supers, are brought into the honey shop from the beeyards. The individual frames are taken out and placed on a conveyor, where the wax seal on the honeycomb is removed. They are then placed in a centrifuge and spun to remove the honey from the combs. From there the wax particles are separated to be used for candles, and the honey flows through a pipe to a holding tank on the floor below, where it is put into barrels for bottling as needed.

Looking Ahead

The consistency and high quality of the honey in those bottles is a source of pride for my family. That quality is due to diligent hard work and generations of experience, but it is also due to the apiary’s location in the Champlain Valley. This area has a long history of bees and is ideal for beekeeping, with a high number of dairy farms and their vast hayfields necessary for growing feed. The alfalfa and clover crops in these fields provide great forage for bees, which in turn produces a light, delicious honey. As it says on the label, “the flower’s fragrance is its flavor.” I often give our signature naturally crystallized raw honey as gifts. When people taste it, they cannot get over the beautiful taste and creamy consistency. Nor can they go back to eating honey from the supermarket.

Like any agricultural endeavor, beekeeping has its challenges. Early on, during the Great Depression, my dad struggled with financial losses, followed by the widespread use of pesticides around the time of the Second World War. After that came the onslaught of mites and diseases that still plague honey bees. Beginning around 2004, Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) began decimating bee populations around the world. Where the annual average losses of a beekeeper’s colonies were typically 15 percent, some beekeepers are now seeing losses of fifty percent or more. These losses are significant because honeybees pollinate 80 percent of the crops grown around the world. One-third of our food crops, including most fruits, nuts, and vegetables, rely on bees for pollination. The ramifications of CCD and the loss of these important pollinators is an environmental wake-up call, and it is finally getting the attention it deserves.

Another challenge facing Champlain Valley Apiaries is the changing landscape of agriculture. Vermont has traditionally been a dairy state and friendly to bees, but there are fewer farms nowadays, and, as a result, there are fewer forage crops for bees. The types of crops have also changed since 1931. Now, dairy farmers mainly grow corn to feed their cows, rather than the legumes that bees require. Farmers also harvest more aggressively, cutting hay more often, sometimes before the clover and alfalfa have flowered. Over time, this will result in commercial beekeepers going out of business; and when we lose beekeepers, we will eventually lose honeybees.

My nephew, Chas, is facing these challenges head-on, as his dad and grandfather did before him. He is looking into growing his own crops for the bees to forage. He is working with the University of Vermont, local farmers, and the Vermont Beekeepers Association to study and improve honey crops, and to maintain Vermont’s agricultural heritage and history of bees. The recent movements of organic farming, farm-to-table, and community-supported agriculture help, too. All of us can do our bit, however small: we can plant flowers that are a good source of nectar for bees, like cosmos, asters, and marigolds; and we can minimize or eliminate the use of pesticides and herbicides in our yards and gardens.

Despite the challenges facing Champlain Valley Apiaries and all beekeepers, Chas is hopeful that better days are ahead and that the Mraz family will be producing and packing honey for many years to come. ![]()