"I KNEW I DIDN'T WANT TO BE A CHEF" —Chef Keith Sarasin

Chef Keith Sarasin shares his journey through grief and love.

The Cook’s Cook asked Chef Keith Sarasin, chef proprietor of Aatma, an Indian pop-up restaurant in Manchester, New Hampshire, founder of The Farmer’s Dinner, celebrated YouTube star, and author of five cookbooks, about his background and evolution.

We watched many of your great videos on YouTube, but let’s begin by asking you to tell us a bit about how you got started and your education.

I grew up in Nashua, NH, with a single mom, so resources were a little tight. When I was 14, I really wanted a mountain bike like every 14-year-old. I assume. Maybe not today. Maybe it’s phones. My mom said that if you want this, you must work for it. So, I applied at a local sub shop, and they allowed me to wash dishes. Many people have glorified memories of when they started in a restaurant, and they knew that’s what they wanted to do. I hated it. But I really wanted that mountain bike. Then, I learned that restaurants are run like a brigade system. There’s a hierarchy. There are ways to do things. There are ways not to do things, which I definitely did a lot of. Mainly, I was instilled with a work ethic that taught me that if I worked hard, I could be rewarded. I decided I was going to stay for a little while.

And I knew I didn’t want to be a chef.

It's been an incredible adventure with many ups and downs.

Can you take us a bit through those moments you spoke of, the frustration, the ups and downs in your early career, and how you moved from the kitchen being a necessity, to the kitchen being a passion?

Getting from 14-year-old Keith to here today is quite a journey. But most of it involves my passion for psychology. I went to school for psychology, and I absolutely loved it. I realized very quickly that getting my doctorate would be incredibly expensive. Even with scholarships, I worked in kitchens throughout school.

It wasn’t until much later in life that I started to follow my closest friend Steve, who absolutely wanted to be a chef, from restaurant to restaurant, getting into mischief and learning quite a bit. When he was diagnosed with cancer much later in life, food really took on a different context. It wasn’t just about instant gratification; food became more about nurturing. Thomas Keller from the French Laundry and Per Se says this. I realized then that I wanted to serve and nurture people, as I learned throughout that process. I had a huge epiphany and wanted to honor Steve’s legacy when he passed. So I just worked my way up in kitchens; the rest is a tumultuous history. I finally founded the Farmer’s Dinner in 2012 after being frustrated sourcing ingredients from all over the world when incredible stuff grew locally Since 2012, the Farmers Dinner has really exploded. We’ve seen 32,000 people, made 115 dinners outside on fields and farms without running water or electricity, and given much back to the local community. It’s been an incredible adventure with many ups and downs.

Between the 14-year-old sub shop dishwasher, Keith, who was working as a dishwasher and starting a business, I followed Steve to different restaurants. We would go to many seafood restaurants because we live in New England, and since I came from a family that consisted of just my mom and me, I found this makeshift family on the ‘line.’ Anyone who’s worked in this industry knows Mother’s Day is a special form of hell. And so we find this trauma bonding. Even though I was going through school for psychology, I always said I don’t use my degree. But I recognized parts of it in myself, in my patterns. We would be just swamped, working a double in a kitchen that’s 120° because no AC can keep up with it, when all you hear is ticket printers, and there’s frustration. It’s being in a foxhole with people you need to rely on. That was this morbid love. This industry is much like the Island of Misfit Toys; we all come from different walks of life.

We all come from different experiences but bond and form a family. That’s one thing that the industry does well throughout that process.

I think grief is a language that we can use to serve love and food.

Where did you find beginnings in food in such a dark time? When did the kitchen, and where did food become that space for a new beginning?

There were a lot of ups and downs. I started the Farmer’s Dinner from a hospital bed. I was diagnosed with diverticulitis, and I was in a hospital for five days, not able to eat or drink. I wondered if it was the end or a new chapter in those moments. Hope is our greatest asset in life. Hope is a very strong emotion. In those dark moments, I decided there was more for me to do for Steve. It was excruciating. Anyone reading this who’s lost a parent or a child or a loved one is in this special club, and you know what I’m talking about. And in that club, you find a new version of yourself. You can never replace that person. You see a new normal. All these lessons seem like they’re just philosophical, but they helped me understand how I wanted to shape my career and how I wanted to look.

When Steve was in intensive care after a failed bone marrow transplant and wasn’t able to talk anymore, he wrote on a whiteboard: “When I get out, can we go to Macaroni Grill? ” It was this incredibly jarring moment when I realized it would never happen. But when you lose somebody so profoundly, I think the biggest lesson is that even though physically that person is gone, that person still exists in these beautiful memories and stories. It’s hard to talk about this. It’s hard to talk about the passing of my mother. But I love doing it because grief is just all this unexpressed love– when that person was there, that’s really what grief is. I started the transition to the Farmer’s Dinner because Steve always wanted to be that chef, and he wanted to do all these things.

Grief and love are integral ingredients for you. How do you think you most honor your dear friend Steve or his biggest legacy in your cookbooks and projects?

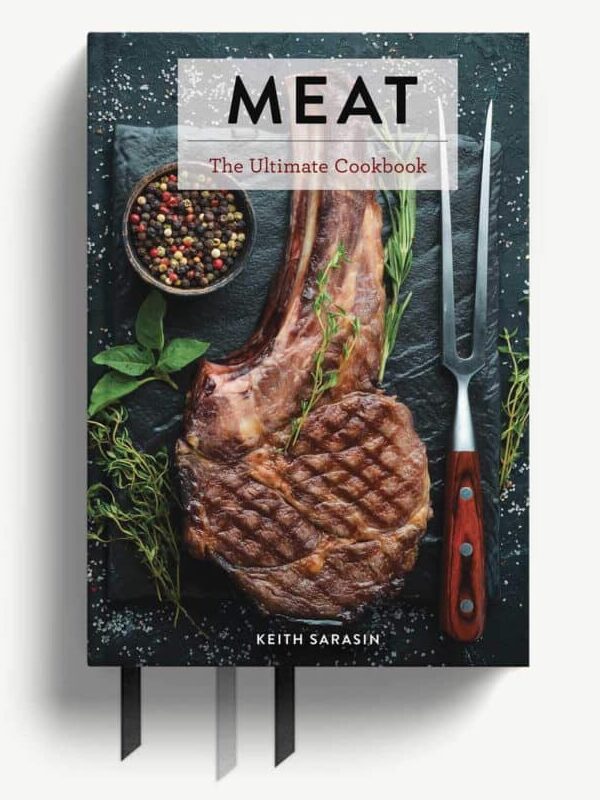

When I wrote my 800-page cookbook on meat, I dedicated it to Steve because this was part of his dream. Food binds and connects us as long as we speak the names of the people we love and share those stories.

We are blips on a cosmic radar, maybe not even a blip, right where we have this finite amount of time. We don’t know how much that is, but somebody only truly dies when their memories go away. When I started writing cookbooks, I knew my name was on it. But as soon as somebody opens one of the first pages you see is a dedication. Writing Steve’s name in there means that he’s gonna exist forever. That’s my theory.

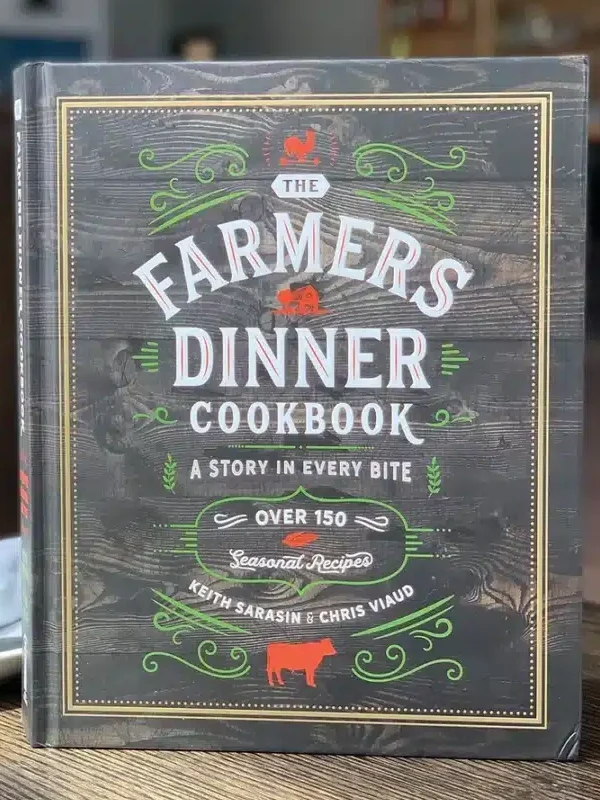

Farmers. Dinner also took on a different side with its cookbook. My mom passed right before that book was published, and I wrote, “Mom, I love you. Your life is a thread woven into every part of me, may I never unravel.”. These people are threads that are woven into us. From a culinary standpoint, they’re also the memories we’ve created with a dish with these deep memories of things that Steve and I used to eat. I’ve done these dishes for my mom for things that she would make. And, you know, she wasn’t a great cook. But being able to take these elements of things that she loved and infuse them in there puts a part of our soul into each dish—getting to that point, as a chef, takes tremendous self-awareness and time.

Hope is our greatest asset in life.