“Aunt Emily is baking this morning!” Mattie Dickinson announces to her brother Ned and their friends. The children cheer. They all know what this means. Baking day is the best day to pretend to be pirates, knights, cowboys or gypsies in the large back yard of the Dickinson homestead.

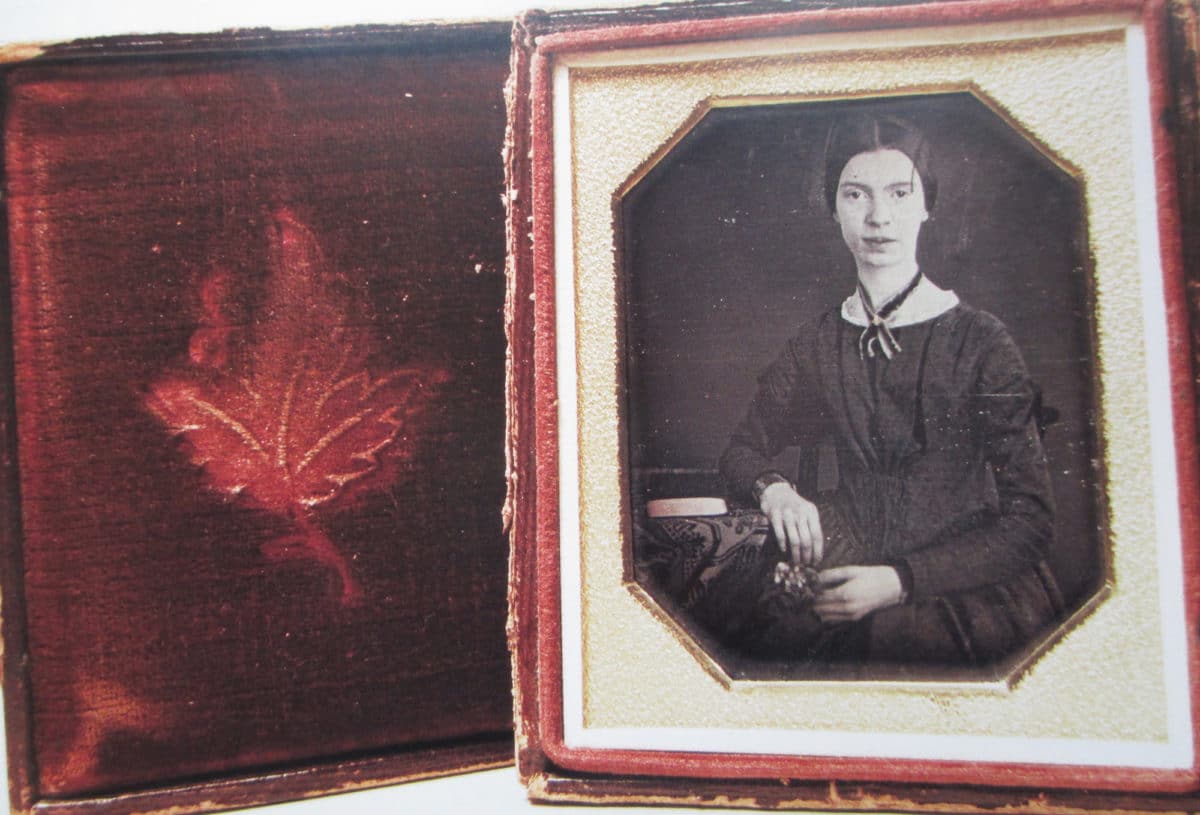

Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886), now recognized as one of the world’s most important poets, was best known to her neighbors as an accomplished baker and a loyal friend who regularly shared her sweet treats with them.

As the story goes, whenever Miss Emily spied the neighborhood children playing in the Dickinson orchards, near the large vegetable gardens, she headed for the pantry, filled a basket with cookies or slices of cake — often gingerbread — carried it upstairs to a window in the rear of the house (so their mothers wouldn’t see), and attached the basket to a rope to slowly lower it to the “storm-tossed, starving pirates” or the “lost, roaming circus performers” eagerly waiting below.

MacGregor Jenkins, the pastor’s son who lived across the street from the Dickinsons, was a regular participant in this play. In the book he later wrote, Emily Dickinson, Friend and Neighbor (Little, Brown & Company, 1930), Jenkins described the famous poet as the children’s “laughing goddess of plenty.” Once when the pantry was empty and she had nothing baked to offer, Miss Emily filled her basket with two cups of raisins, a rare treat for the children, who had only eaten them baked in cookies or cakes. The intense sticky sweetness was too delightful to stop eating after a handful or two, so they ate them all, a choice that left them with tummy aches for the next few days.

No one knows for certain why Emily Dickinson became reclusive, refusing social invitations or receiving guests. During those years of her life, she enjoyed a small circle of her closest friends. Should any of the children knock on her door, they were always warmly welcomed. Once, as MacGregor Jenkins recalled, the poet remarked in the kitchen, “You know, dears, if the butcher boy should come now, I would jump into the flour barrel.” They did not see their loyal friend as eccentric, but as one whose humor, generosity and loyalty was ever-present.

Dickinson also shared her baked goods with neighbors who were ill or in need, or just because it was a fine thing to do. She frequently sent a flower or a poem along with something she’d baked. When her dearest friend, Susan Gilbert, moved to Baltimore to teach school, Emily sent her chocolate caramels and rice cakes that she’d concocted in her kitchen.

In a letter Miss Emily wrote to one of her friends when she was a teenager, she excitedly announced that she would be learning to bake the next day. Baking bread was a daily routine in most kitchens in the nineteenth century. Emily quoted her father as saying that he wouldn’t eat bread unless it was baked by her. She did win a prize for her “Rye and Indian Bread” in a competition at the local Cattle Fair. Her black cake (similar to fruit cake) and her coconut cake were family favorites, but the children especially loved her gingerbread. Here’s her recipe as she’d written it:

Gingerbread

1 quart flour 1 Tablespoon ginger

½ Cup butter 1 teaspoon soda

½ Cup cream 1 teaspoon salt

Make up with molasses

Tour guides at the Emily Dickinson Museum who have made this recipe experimented with the quantity of molasses that Emily used, concluding that “one cup or so is just about right.” Another variable is the quantity of flour. When I made it, I used 3 cups of flour.

Emily’s gingerbread was oval-shaped. If you’d like to make as it she did and don’t have small oval pans, you can use a cast iron muffin pan. According to MacGregor Jenkins, Emily often glazed her gingerbread and decorated it with a small edible flower like a pansy.

One of the guides at the Emily Dickinson Museum told me she presses the thick batter into a large baking pan, bakes it for 12 minutes, and after it cools, cuts it into bars. Bars would certainly be more portable in terms of being lowered from a second story window and could easily be glazed, but if you are like me, there’s nothing like warm gingerbread and freshly whipped cream.

Remember when you’re plugging in your electric mixer and watching it rapidly fold your ingredients together, Miss Emily didn’t have one of those tools. Maybe when she was patiently stirring, she had the time to consider a few poetic ideas or lines. She wrote a poem on the back of a recipe once, and she wrote one on the back of a Parisian chocolate wrapper. Was she baking when the idea for poems occurred to her? It seems likely.

You might want to include a pencil and a piece of paper in your list of ingredients when you try this recipe. Who knows? A fine poem may come to you as you begin to smell the tart scent of ginger fill the air in your kitchen! ![]()