Waffles have a deep, storied history dating from the 12th century or even earlier.

What we perceive as a waffle today grew up over time from a thin, flat, often elaborately impressed, crisp biscuit, cooked between two hot incised metal plates called moule à oublie or moule à gaufre that date from at least the 12th century. Contemporary survivors of this tradition are the honey combed gaufrette, and the filled stroopwafel. By the 16th century a thicker, less decorative waffle, with uniform indentations, emerged.

The first appearance of the use of a leavening agent in waffle cookery was in the Antwerps Kookboek, in the 17th century. The recipe used ingredients familiar to us now: wheat flour, sugar, butter, eggs, (brewer’s) yeast. They were simply called groote wafelen (big waffles). Because sugar and certain other ingredients were costly, these waffles were for noble and upper class consumers; honey sweetened, grain-based waffles satisfied the rest.

By the time of the German-Moravian artist, Georg Flegel (1566–1638), to whom this painting (below) is attributed, the waffle looked much as it does today.

The Brussels waffle, the Gaufres de Bruxelles, was no doubt available in Belgium in the early part of the 17th century. Belatedly, the first claim to the “invention” of the Brussels waffle was made by Florian Dacher, a Swiss baker in Ghent in 1842. It is safe to assume that the general recipe and method had been in circulation for a very long time before commercial bakers popularized the name, branding it with the tradition of place-of-origin pride.

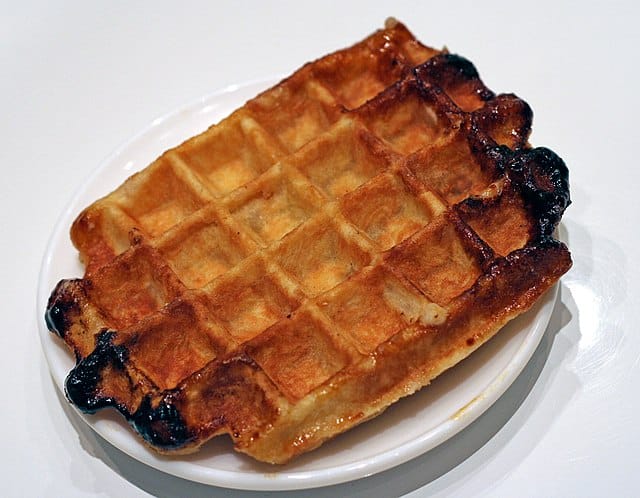

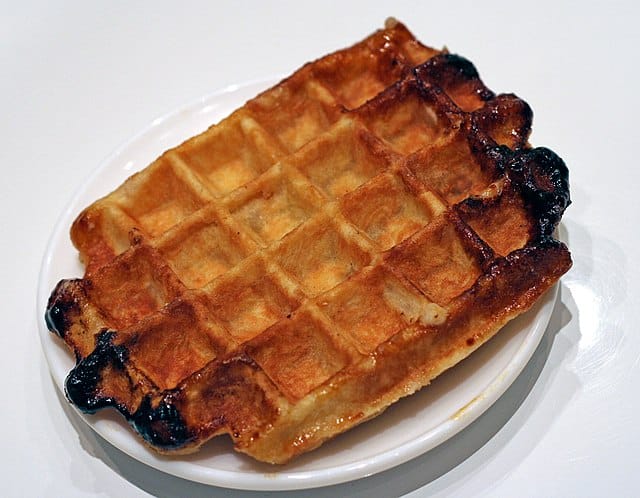

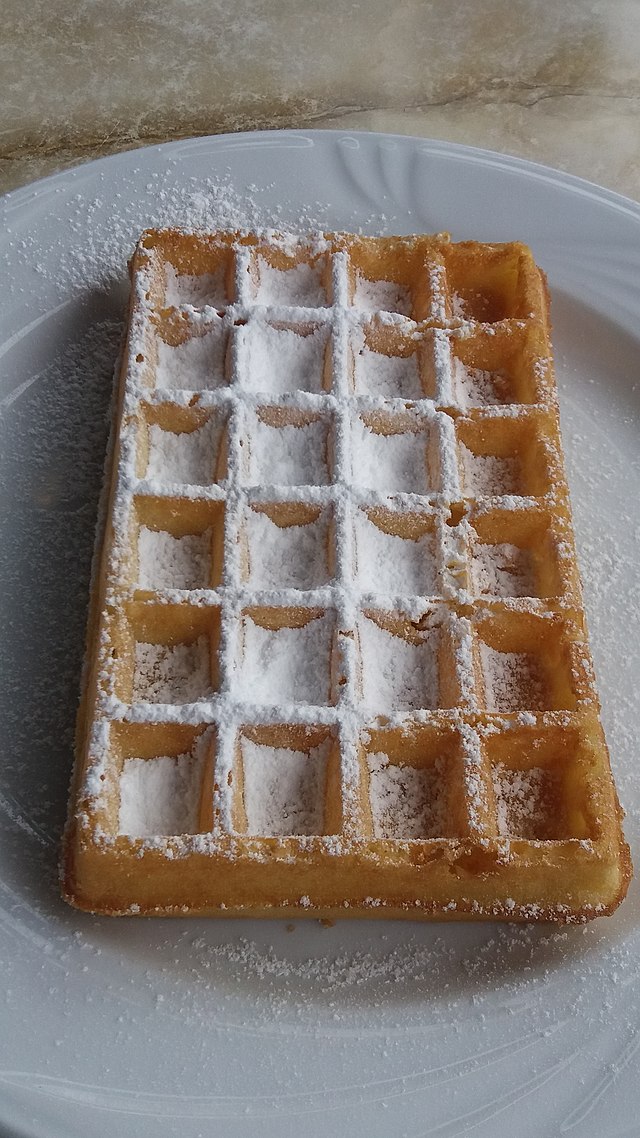

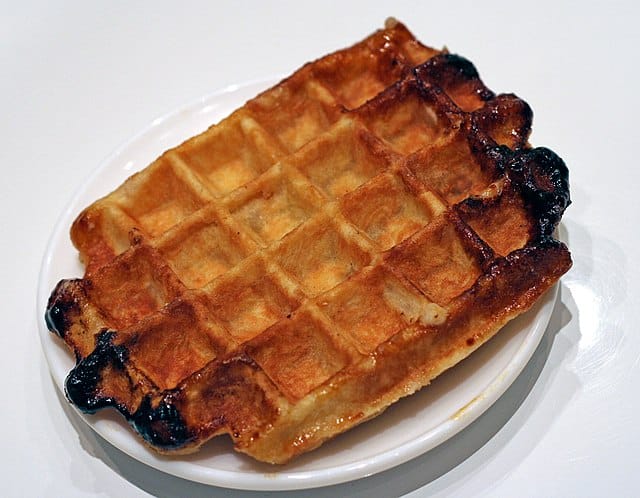

The distinguishing characteristics of the Brussels waffle include the contrast of a crisp exterior, with the nearly-not-there lightness of the interior, its square or rectilinear shape, and that it was eaten out of hand.

Of course, it was not without competition. Liège waffles were created at the request of the Prince (Bishop) of Liège of Wallonia, nearer the German border. Smaller, thinner, oval-shaped, denser (made from dough rather than batter), and therefore chewier, the Liège waffle has the addition of crunchy nuggets of caramelized pearl sugar. Like the Brussels waffle it was (and is) a strolling street snack, sold outside of train stations, churches, at fairs, in parking lots, wherever good foot traffic proliferates, and is customarily eaten unadorned.

Neither the Brussels waffle nor the Liège waffle were ever a breakfast item.

As sugar became more plentiful and affordable in the 18th century, waffle popularity soared. Recipes included other trendy imports — spices, coffee, and chocolate. Many of these creations carried the name of their place of origin: Schwedische Waffeln (from Sweden), Gauffres à l’Allemande (from Germany), Gaufres de Lille (the city in French Flanders).

The Waffle in America

In 1744, in the American colonies, “Wafel frolics” were a hands-on waffle-making social event. No news to the Dutch who had already established their own waffle culture in New Amsterdam (New York). That President Thomas Jefferson is said to have imported the first long handled, deep-welled waffle iron towards the end of the 18th century attests to the waffle’s popularity.

The first patent for a stove-top waffle iron was issued to Cornelius Swartwout of Troy, N.Y., on August 24, 1869, which these days is National Waffle Day. In 1911, General Electric developed a prototype for the first electric waffle iron, and soon the waffle infiltrated many a kitchen table. The Americanization of the waffle was well under way. Just when it became a primarily a breakfast item with butter and maple syrup, eaten with knife and fork, like an up-cycled pancake, is open to conjecture.

The first patent for a stove-top waffle iron was issued to Cornelius Swartwout of Troy, N.Y., on August 24, 1869, which is now National Waffle Day.

In 1911, General Electric developed a prototype for the first electric waffle iron, and soon the waffle infiltrated many a kitchen table.

In 1955, a businessman and a short order cook got together in Avondale Estates, Georgia, and opened the first Waffle House®. Soon they had four locations, then twenty-seven, and today there are over 2,000. They were opened all day, all night, all year. Their waffles are the size of a dinner plate, not too thick, divided into quadrants served with maple syrup at the ready. And although waffles have been around for centuries in one form or another, the Waffle House waffle set the standard in America for size and thickness.

The Savory Waffle: What’s Old is New

Although perceived by many as a breakfast treat, the waffle had also served as a plinth to support a variety of savory toppings — snapping turtle, crayfish, duck, pork, and more since the early 19th century.

A few years ago a chicken-and-waffles revival took place that had more than a few folks scratching their heads, but eager to give them a try.

As an ode to old country roots, Pennsylvania Dutch chicken and waffles was widely enjoyed by the mid 19th century. Depending on your circumstances it was waffles with chicken gravy, or with chicken and gravy if you could afford it, and the waffles were not sweetened. The topping was tender stewed chicken and vegetables, in a broth thickened to the consistency of a sauce. Throughout Pennsylvania, “waffle palaces” proliferated mostly for visitors, and “waffle suppers” were (and still are) popular among locals. “Chicken and waffles was always a special occasion-dish, even if that special occasion was only Saturday evening supper,” said William Woys Weaver, in his book, As American as Shoofly Pie.

Some say fried chicken and waffles drifted north during the 19th century from southern kitchens during the Great Migration. Others say fried chicken and waffles was a “Harlem thing” launched at Wells Supper Club in the 1938. The inspiration might have been Bunny Berigan’s 1935 jazz instrumental, “Chicken and Waffles.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=01H-ysssQeg

The crispy combination was said to satisfy the very late night crowd of jazz musicians and nighthawks offering the tastes of supper and breakfast on one plate. Whichever origin story is true, fried chicken with waffles certainly fulfills the salty-spicy-sweet-crunchy American compulsion.

All of this, however, surely was pre-dated by catfish and waffles.

A tradition in Philadelphia of seasonal catfish and waffles grew up along the Schuylkill River, beginning in 1813 in Mrs. Watkins’ Falls of the Schuylkill Hotel (above). From late May through October, catfish were scooped up from the Mifflin Run that flowed past the hotel into the river. The Inn had a holding pond where the fish were stored until needed. Talk about fresh. All along the Schuylkill, and elsewhere, fried catfish and chicken and waffles became signature dishes upon which long-lived reputations were built.

In spite of all of this waffle love and history, the traditional Brussels waffle was to make a triumphant return, bringing back the old world charm and appeal of the irresistible street snack.

The popularity of the Belgian waffle was propelled into the culinary spotlight at the 1964 World’s Fair. It was the suave, merry-making, determined Belgian, Maurice Vermersch who introduced thousands to his giddy, memory-making Belgian icon.

Vermersch understood that the Brussels waffle challenged most Americans’ geographic knowledge. They knew of Brussels sprouts, but probably could not find Brussels, the capital of Belgium, on a map. He called his Bel-gem, but the more generic Belgian prevailed as the universal name for the deep pocket waffle. Although Madame Vermersch thought the addition of a tower of whipped cream, embellished with sliced strawberries was an abomination, that is just what a surprising number of people wanted – as many as 2,500 a day.

In Brussels, and elsewhere, it remains a street snack, in America it has become a regular menu item for breakfast and brunch.

Centuries have proven the waffle’s staying power and versatility. Served with sugar, whipped cream, strawberries, chicken stew, fried catfish or chicken, it is the persistent, quiet presence of the waffle that makes the magic. The one constant is that, however it is put to use, the waffle has always been a delightful, approachable indulgence.![]()