Fruitier Than A Nut Cake

The traditional English fruitcake emerged in England in the 13th Century when the first precious dried fruits arrived from Portugal and the Mediterranean. Plum was the generic term for all dried fruit, so when they were compressed into a desirable confection they were all called Plum cakes. Fully half the weight of the cakes consisted of dried fruits — a delicacy reserved for the well-to-do.

It is shocking that fruitcake, the icon of Christmas delight, receives so little respect.

It has been heaped with scathing scorn, and has been the object of barely funny derision. Its often chaotic jumble has been described as an inedible metaphor for a chaotic life. Some have reduced this cornerstone of American family values to a doorstop. It has been accused of having geologic aspirations. It has even been suggested that fruitcake is only fit as a stand in for the Yule log, or be employed as a speed bump. What it has become bears little on where it came from.

Scarcity, or abundance, of any ingredient often influences the desirability or ubiquity of a food or dish.

Dried fruits had been around since fresh fruits were left in the sun. There are figs and raisins in the Bible, records of dried fruits in Ancient Mesopotamia, and as part of the pantry inventory in homes in Ancient Rome.

Along with so much that was eclipsed during late Antiquity and the Early Modern eras fresh fruit was suspect, only eaten by the poor or used as a sweetener by those for whom honey and sugar was beyond their reach.

Dried fruits eventually became more available, and affordable. When the price of sugar dropped in the 19th century (when the market supply was supplemented by extracting sugar from beets), fruitcake making flourished. When nuts became more commonplace, they were added generously to the cake.

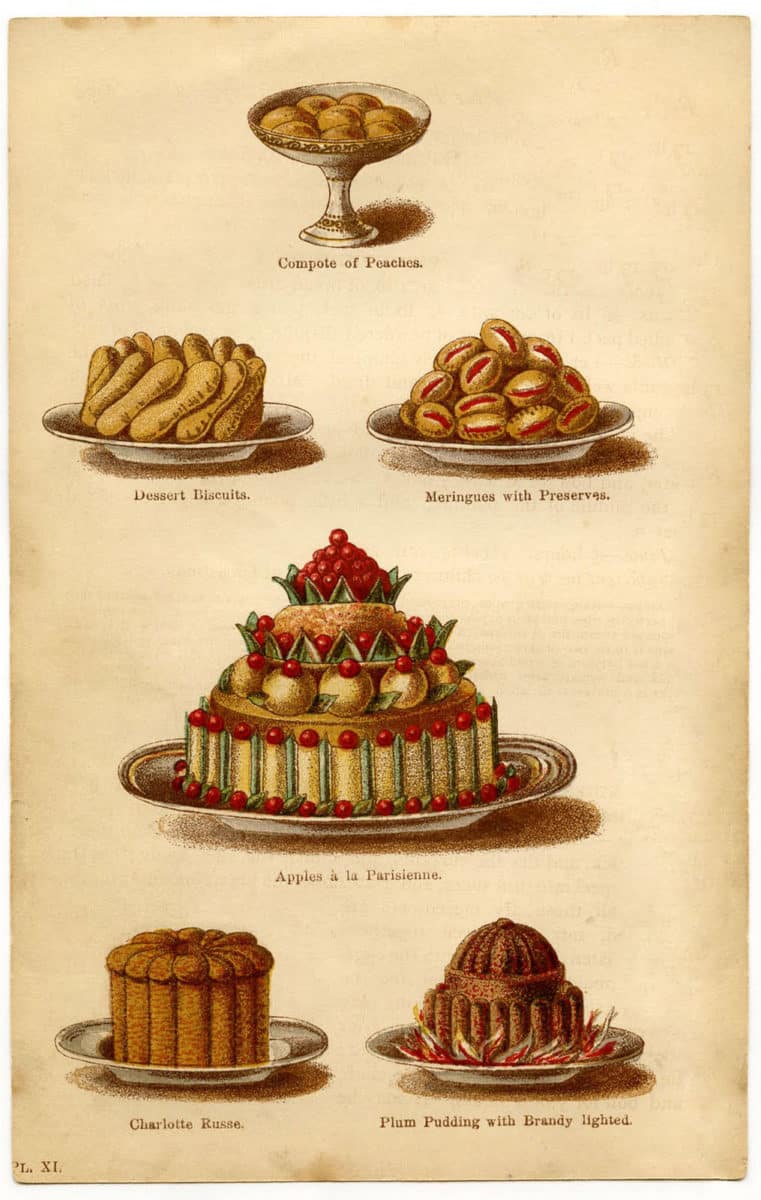

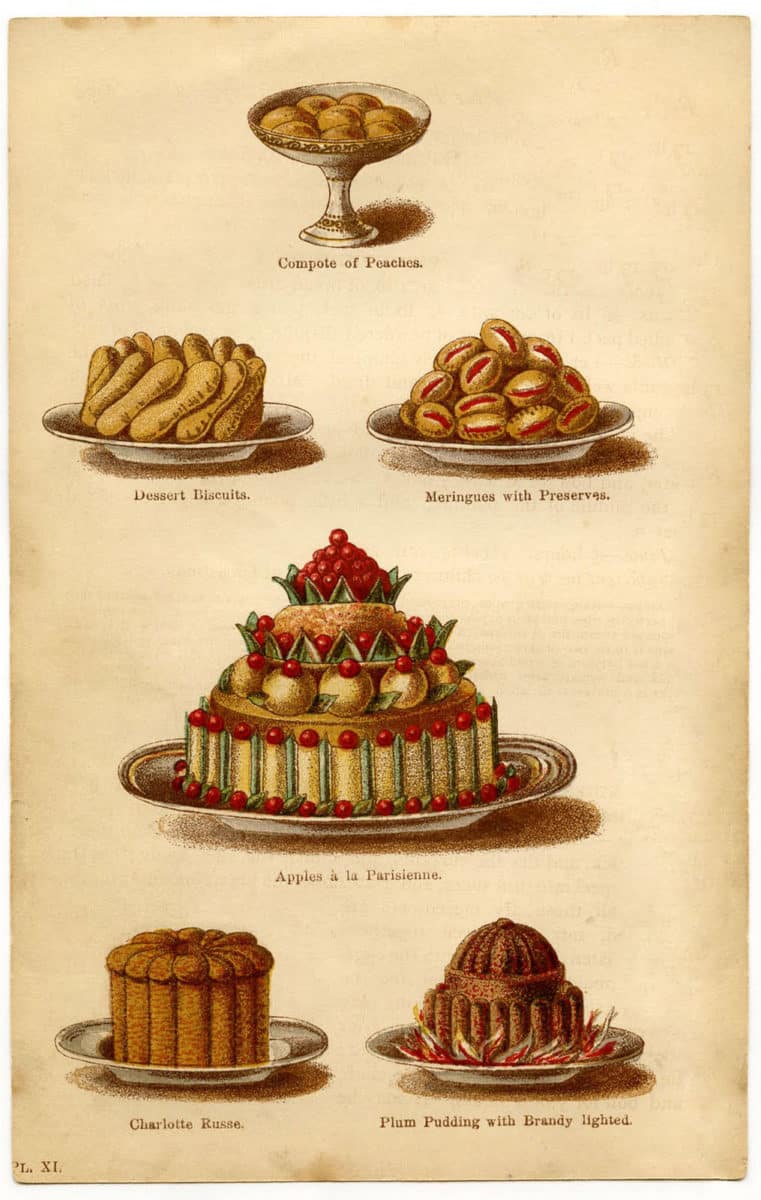

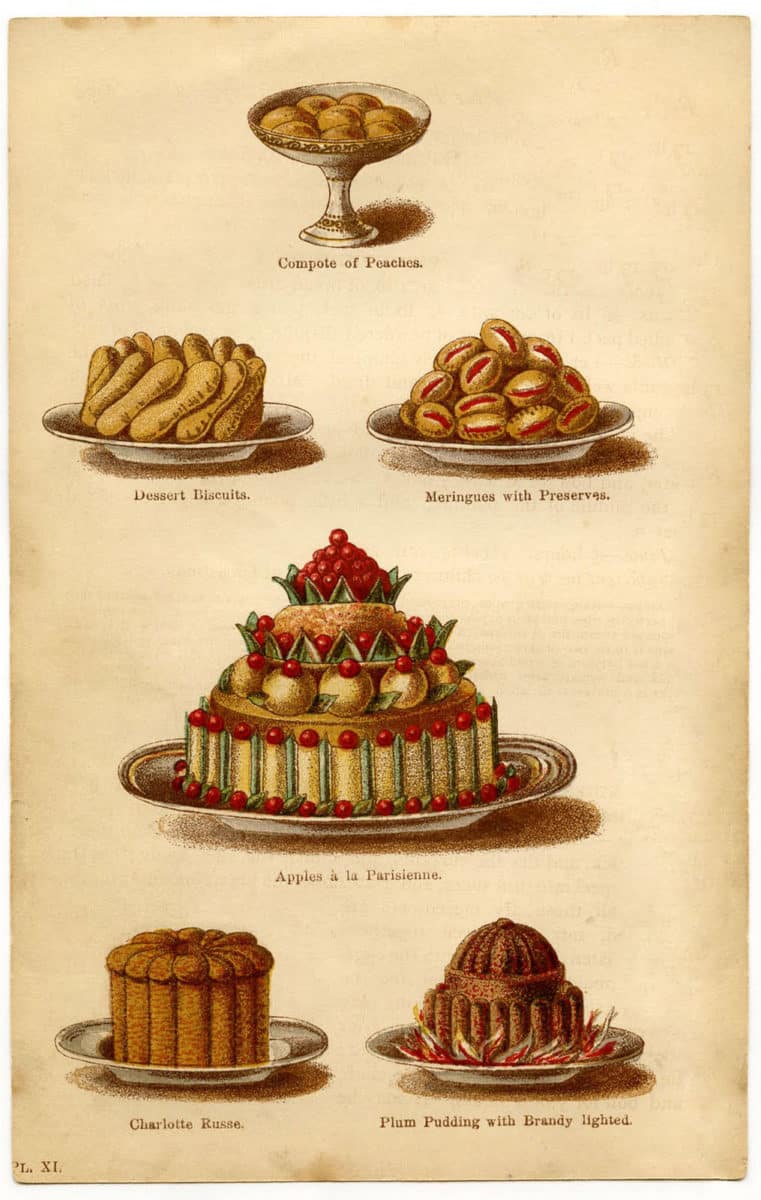

The fruitcake, in its many manifestations, became a catch-all of sultanas, candied peel, glacéed cherries, dried fruits, hazelnuts, almonds, walnuts, or pecans (native to North America). While often made in a brick-shaped loaf, when made in a ring mold it resembles a bejeweled crown.

Not surprisingly for something that has existed for so long, many are the variations on the theme.

For the Scots, the modern fruitcake’s progenitors include the Black Bun eaten since 16th century at year’s end on Hogmanay. It was, however, their almond topped Dundee Cakes that emerged in the late 18th century, and proliferated in the 19th, that became a Christmas treat. Nigella Lawson suggests one “feed” the cake with “good Scottish Malt Whisky” the same as one would a “traditional” fruitcake.

In Germany, a similar loaf-shaped cake, Christstollen (today just stollen) is the fruitcake of the holiday. A version has been made since 1427 when it was a presence at the Saxon Royal court. Advent austerity was modified in 1490 when, after payment of a modest tax, butter was added by Pope Innocent VIII to the baker’s permissible ingredients list. Excluded from the tax was the Prince Elector and his family. The tariff to all others was 1/20 of a gold Gulden payable to the fund to support the building of Friedberg Cathedral.

The closest the Italians have to a comparable fruit and nut confection is Panforte, a specialty of Sienna, popular with Crusaders in the 13th century. The flattened disc was made ridiculously decadent when chocolate was added. Tradition had it that there should be seventeen ingredients to commemorate the contrada, or the districts within the city of Sienna.

In England and Colonial America, the fruitcake was a celebratory cake as early as the 18th century, and persists today as the bride’s cake (wrapped in marzipan), and, most importantly, as a Christmas tradition.

In the 19th century the estimable Mrs. Isabella Beeton set out to codify, simplify, rectify and modify all of the activities of a proper Victorian home. In her, Book of Household Management, published in 1861, a monumental work of over one thousand pages, there are 1,877 numbered entries in the recipes section — the tradtional Christmas fruitcake is recipe #1754. Here, for the first time recipes appeared in a format that became the standard: ingredient list, method, preparation time, cost and number of servings. The 25 year-old Missus was the first to provide more specific measurements, collect, test, collate and standardize every recipe, doing exhaustive background research on ingredients, food chemistry, farming and cooking methods. By any measure, it was an enormous success, selling over 60,000 copies in its first year.

We owe a token of gratitude to her, as we do Charles Dickens, for establishing the fantasy of Victorian England, and especially the Victorian Christmas that persists in the minds and traditions that we still attempt to practice.

Of all the noble, real or imagined, Christmas traditions, none seems to have veered so far off the track than the traditional English fruitcake.

Pick up a sorry, leaden slice of garishly colored chunks of unrecognizable candied fruit mortared together by a dark, cloying, grainy batter and it is hard to get past the first hesitant bite. Often the fault “lies not in our stars” but in the faulty hands of the misinformed baker.

Perhaps the problem lay with the previous perversions of commercial production. Some producers have partially reclaimed the tradition from hilarity. Harry & David offer a one pound, gift-tinned cake that has all the right elements. Eilenberger’s Bakery takes a Texan turn by loading in pecans, since pecan pie is the “state pie” of Texas. Georgia’s Claxton Bakery offers a loaf-shaped fruitcake “with a crown.” If you desire a more celestial and brandy based fruitcake, the Trappists at the Holy Cross Abbey at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia have been doing God’s baking since 1950.

You COULD order one online, and make one at home, and compare. It could be an after Christmas dinner amusement; just be prepared for all the tired jokes about fruitcake.

To get snuggle-up-to authenticity in a traditional English fruitcake, you’ll have to bake your own.

And it isn’t all that difficult.