In my years of living in China, despite traveling often, I had done all I could to avoid joining a tour group. Something about them just felt wrong—a lack of independence that recalled childhood bus trips with my grandmother, that thoroughly defied my image of myself as a worldly, capable dude. But in Xinjiang, where countless military checkpoints present a formidable obstacle to solitary foreigners, I no longer had a choice. Hours outside the city, there was a lake, high in the mountains, so tall it snowed even in summer—and only one way to get there. Fortunately, after an hour of slow group-shuffling, we were freed for an invigorating, if somewhat humbling high-altitude climb. But, to my hunger-addled brain, that was all just an appetizer for the real highlight of the trip: our visit to a local restaurant.

Afterward, exhausted from the climb, we shuffled onto the bus, barely speaking—but, having been promised “an exquisite selection of twelve local dishes,” we became instantly alert upon sighting the restaurant. Ravaged by hunger, we circled the table looking eagerly toward the kitchen, drawn by the roar of flame against cast-iron woks. No doubt there would be a massive slab of Xinjiang’s famous roast lamb, charred and finely dusted with cumin. The other obligatory dish would be “big plate chicken” in its sumptuous bath of spices and chili oil; then, of course, yellow rice cooked in lamb fat, topped with a generous pile of more braised lamb…. Though, in retrospect, the tour guide’s sudden disappearance should have offered some warning of the disappointment to come.

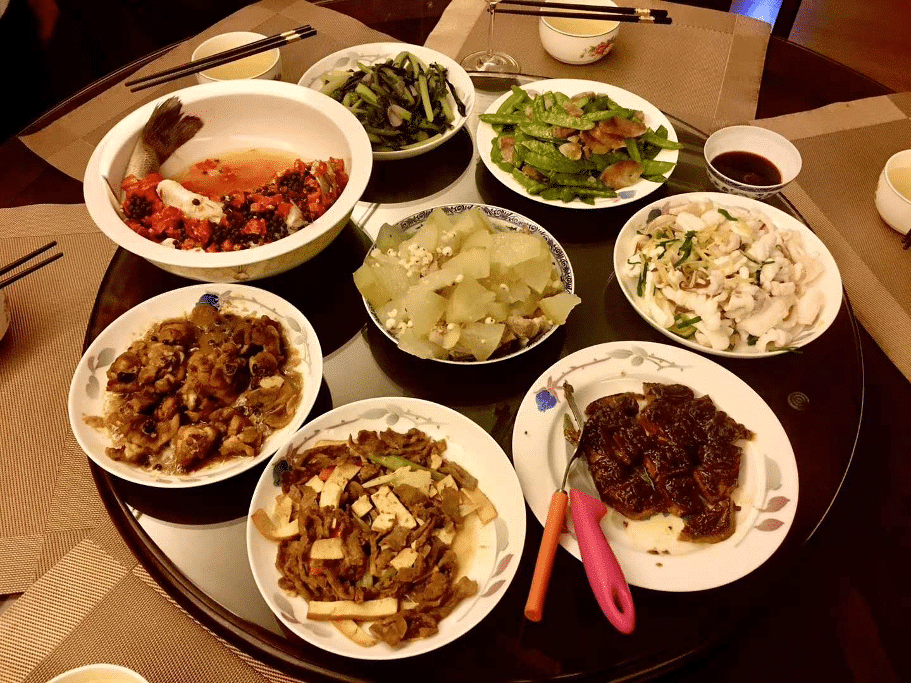

Our twelve dishes arrived in rapid succession, but none of them contained more than a few bites of meat! Instead, servers piled the rotating table with mountains of pickled cabbage, steamed greens, fried cauliflower, and braised pumpkin. This must be just the start, my companions grumbled, eyes alert for whatever might arrive next. But then came green beans in black bean sauce; radishes in pork-bone soup; spicy tofu with a few crumbles of pork; and, at last, a single lonely plate of fried rice. My companions, increasingly disheartened with the appearance of each dish, picked idly at their beans and stared morosely at their tofu. More than a few whispered plans for another meal after the tour finished. Unfortunately, the tour guide reappeared just in time to announce we would spend the next few hours being ferried between tacky, out-of-the way gift shops.

Of course, the other tourists (all mainland Chinese) had good reasons to complain. The tour guide had fed twelve people for approximately 200rmb: fifteen American dollars. These “local” dishes were available at school-canteens and cheap restaurants all around the country; probably many in the group could cook similar food themselves. In a country that increasingly prizes meat on special occasions, our tour guide had delivered the most common everyday food. But the meal’s very commonness reveals the crucial role of vegetables in everyday Chinese cuisine—a diet whose benefits quickly become apparent during the briefest stroll around any Chinese city.

Beneath it all lies a simple, yet powerful philosophy of emphasizing one or two ingredients on a plate at a time, and putting as many plates on the table as possible. In China, you’ll rarely see the “stir-fry” of mixed vegetables so common in the west—a dish whose self-sustaining completeness suggests the swagger of a full meal or (more likely) the diminutive poise of the only plant at a party otherwise dominated by meat and bread. Instead, many plates will be 80 percent cabbage, 80 percent green beans, or 80 percent fish—though that last twenty percent can be almost anything. Many dishes suffer an almost peculiar isolation, a need for companionship, as anyone who has ever tried to eat a pound of fried lotus root with rice for lunch can attest. But each remains a valuable, distinct unit in itself.

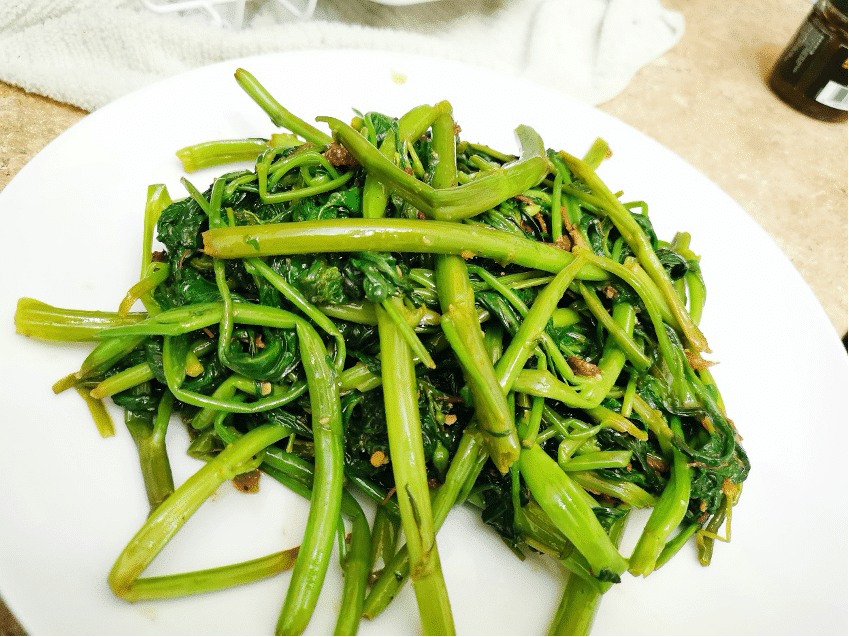

That helps to explain why, amidst our bountiful harvest of vegetables, no dish had been treated as an afterthought. In China, you’ll never see that one meager bowl of brussels sprouts in butter, ignored amongst the other, heavier dishes on display—or, worse, that weak little pile of “seasonal veg” hidden beneath the rocky crags of a steak. Yes, when I was growing up in Michigan, we had big vats of vegetables. But nothing in China could be more different from the soppy cauldrons of cabbage that terrorized my childhood; the pasty husks of canned lima beans; the mushy, tasteless bags of microwaved peas that even my mom didn’t actually want to finish. In America, vegetables often reminded me of that poor kid who got picked last in gym class. But here, even with twelve dishes on the table at once, each one of them was an important member of the team.

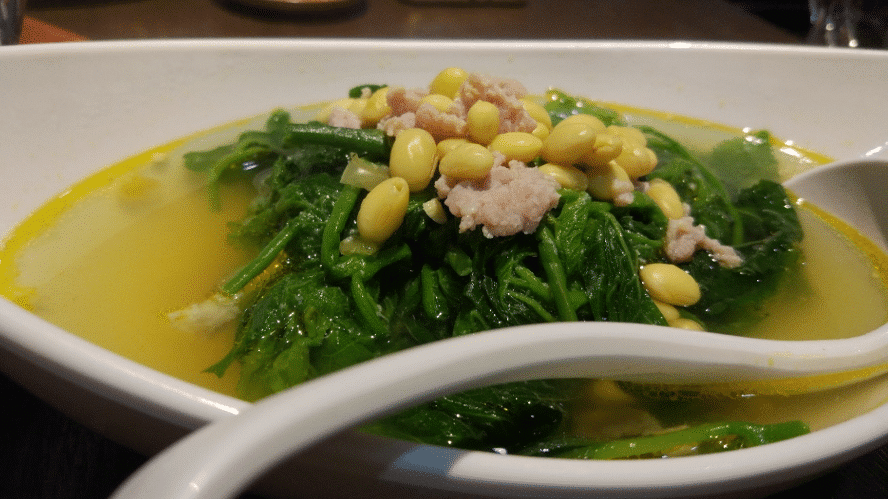

Many Chinese, particularly the country’s most impoverished, grow up eating smaller versions of this meal every day—a striking contrast to the frozen dinners, baloney sandwiches, and packaged mac and cheese of the American poor. However, the patterns aren’t so different even among higher-income Chinese. To envision an average meal, imagine that one dish is tofu in abalone sauce, another is steamed choy sum with sweet soy sauce, and the third is green beans stir fried with a little pork…all orbiting a single plate of roast chicken. Even a hungry group will rarely get more than one dish that is all meat. The result is an impressive harmony of flavors that effortlessly hones in on the USDA’s recommended portion sizes, filling half the plate with vegetables, a quarter with protein, and a quarter with carbs. But most importantly, even carnivores don’t feel like they’re on a diet.

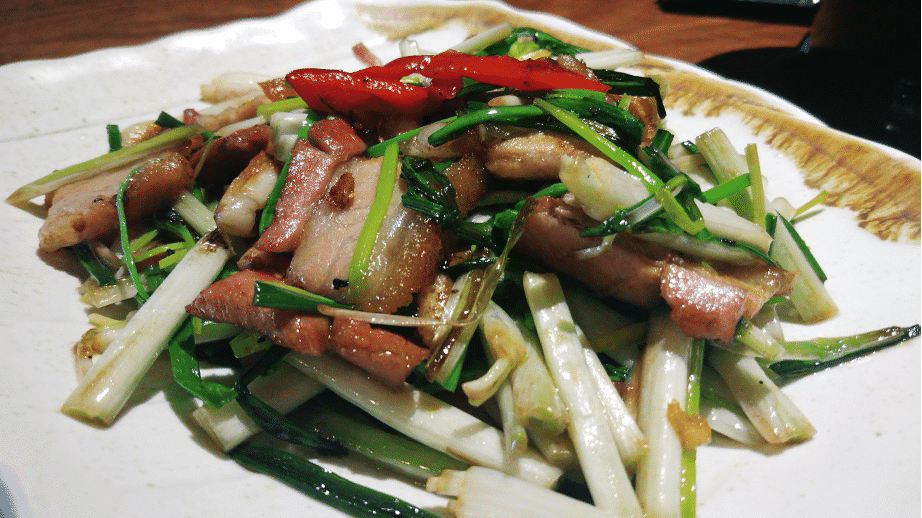

People often say it’s “hard to be a vegetarian in China,” as the trace amounts of meat in so many dishes amply illustrates. But for omnivores, this clever tactic maintains a strong nutritional profile while decreasing both the cost and environmental impact of each dish. On average, you’ll come across a piece of meat every three of four bites, but you can always taste the flavor throughout the dish. This keeps the food savory and satisfying even when the only meat is a pork—which is often the case. And, though these small portions might sound uninviting, the reality is just the opposite. There’s nothing like mining a mountain of cauliflower to unearth that hidden deposit of pork belly, or finding the last piece of sausage beneath a leafy bed of tong-cai. For me, it can be more enjoyable than eating a whole dish of it straight.

Chinese food benefits from a dazzling array of sauces that contribute unique flavors but few calories—another striking difference from the fatty abundance of western cuisines. Most importantly, no Chinese chef faces the challenge of whether to drown their broccoli in butter or bury it beneath cheese. This temptation has vexed me since I first began to cook. When I glaze my roasted vegetables simply with vinegar or spritz them with lemon, I know I’m making a sacrifice. I feel the same when I eat a sandwich without mayonnaise, when I substitute yogurt for heavy cream, and when I struggle to not eat that massive hunk of cheese. To me, lighter versions of traditionally hearty dishes–veggie ramen, zucchini lasagna, or mushroom “steaks”–can be unsatisfying. The shadow of meat refuses to be dispelled, leaving an awareness of substitution, of an emptiness only partially filled.

There was no feeling of emptiness as those twelve Chinese dishes made their way around the table. Instead, each vegetable was a satisfying part of a larger, more impressive whole. When I finished with the salty black bean doujiao, it was time for the spicy chili tofu. Next, the light, unexpected sweetness of braised pumpkin washed the heat away, leaving the palette cleansed for the charred, vinegary bite of fried cabbage with a few slivers of pork. At last, all you wanted was a bowl of fried rice to finish it all off. The banquets at fancy Chinese restaurants are extravagant displays of flavor, creativity, and expensive ingredients; but even the best of those meals have rarely lingered in my memory quite like this one. It’s the most vegetables I’ve ever seen on a single table at once, served in a way that could only happen in China.

Of course, as China rides the crest of its new economic prosperity, this way of eating has already become less widespread than it once was. For many Chinese under 30, this is the age of milk tea, packaged snacks, and McDonalds; with rare exceptions, the young people at a traditional, local restaurant are likely to be there with their parents. Even their elders, eager to chew the fat of modern abundance, grow hungrier and hungrier for meat. As a generation less versed in cooking comes of age, it’s not impossible to imagine fewer vegetable dishes at each table—or perhaps, following in the footsteps of its neighbors Japan and Korea, China will start eating pre-prepared convenience store meals like everybody else. But at least for now, few countries equal China in its abundant, clever use of fresh vegetables.

Fortunately, I wasn’t entirely alone in my enjoyment of the meal—though that ghost of China’s meaty future refused to be dispelled. In time, my group’s frustration became grudging acceptance, but never quite appreciation. Plates were emptied; bowls of rice refilled in preparation for more. It was an atmosphere of reluctant acceptance, of a populace only briefly contented—of hungry eyes gazing upwards at the thought of something more. Someday, a meal like this might become the province of specialty restaurants aimed at health-conscious youths, eager to cut calories and pay homage to a vanished era of whole foods; but for now, all agreed, it had been nothing special. It had been healthy, delicious, and sustainable. Perhaps it was even uniquely Chinese. ![]()