Ricotta alla torta, which is also known as torta di ricotta, or ricotta tart, has roots stretching back to the Renaissance. In the tradition of early Italian baking, it emerged as a simple yet refined dessert: lightly sweetened ricotta cheese encased in pastry or baked on its own, served during banquets, religious feasts, and family celebrations. Over the centuries, this humble ricotta cake evolved into a beloved dessert across Italy, maintaining its essential character while adapting to local tastes and ingredients.

Renaissance Origins

The earliest forms of ricotta cake can be traced to the 15th century, when culinary masters like Maestro Martino da Como and Bartolomeo Platina documented recipes for cheese-based sweets. Martino’s Libro de Arte Coquinaria includes several preparations for pies made with fresh cheeses such as ricotta. These early tarts combined ricotta with eggs, sugar, spices like cinnamon, and often a touch of rosewater or citrus zest. They were enclosed in thin pastry crusts or simply baked until firm. Not long after, Bartolomeo Scappi, chef to several cardinals and popes, featured several different ricotta tourtes in the pages of his L’Opera (1570), including pumpkin and strawberry tourtes. Ricotta cake and pies were showpieces at Renaissance banquets, served to impress guests at courts and papal feasts.

The use of sugar in these early ricotta desserts is a telling sign of their Renaissance context. By the 16th century, sugar had become more readily available in Italy largely due to colonization of the New World and access to sugar cane. Sweetened cheese tarts were a novelty made possible by this “new” luxury ingredient. They were likely served on special occasions, a fine sweet course to conclude opulent meals. The combination of mild ricotta with sugar, spices like cinnamon, and sometimes floral waters (as in Martino and Scappi’s recipes) created a delicately flavored treat that fit Renaissance tastes for sophisticated but extremely sweet dishes. In an era when food often signified status, a ricotta pie enriched with costly sugar or decorated in gold was the ultimate symbol of luxury at the table.

These tarts were considered refined dishes suitable for important meals. Sugar was still expensive in the 15th and 16th centuries, which meant that desserts like torta di ricotta appeared at feasts for the wealthy or on major religious holidays.

Evolution Through the Ages

As sugar became more available and culinary tastes shifted, ricotta pies remained popular in both grand and modest kitchens. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the basic Renaissance-style ricotta torta evolved but did not radically change. Recipes increasingly emphasized subtle flavorings like lemon peel, orange blossom water, or vanilla as these ingredients became more common through trade.

The structure of the dessert also shifted slightly. Some versions included a single thin pastry shell, while others were crustless. Bakers adjusted sweetness levels depending on access to sugar or regional preferences. In parts of central Italy, honey remained a common sweetener well into the early modern period, resulting in ricotta tarts with a lighter, floral note.

Throughout this time, torta di ricotta continued to be associated with festive occasions. It appeared at Easter, particularly in rural communities where fresh springtime milk and whey provided the best ricotta. In cities like Florence and Venice, more elaborate versions with candied fruit or liqueur flavorings were served at banquets or gifted during holidays.

One of the most enduring and historically significant versions of ricotta cake is the Jewish cassola of Rome. Dating back to at least the Renaissance period, cassola emerged from the kitchens of the Roman Jewish community, one of the oldest Jewish communities in Europe. Unlike the more elaborate tortas of the Christian tradition, cassola reflects a different approach: it is a crustless, rustic cake made simply with fresh ricotta, eggs, sugar, and sometimes raisins and a touch of citrus zest or cinnamon. Cassola is traditionally prepared for holidays like Shavuot, when dairy foods are customary, but it also appears during Passover, using flourless variations to comply with dietary restrictions. Its simplicity highlights the natural sweetness and richness of good ricotta, and it represents how Jewish cooks adapted local Italian ingredients and flavors into their own culinary heritage, even under the often harsh restrictions imposed by life in the Roman Ghetto.

Regional Variations

Today, regional styles of torta di ricotta still reflect these early traditions. Across Italy, the unifying thread is the gentle sweetness, light texture, and the starring role of fresh ricotta.

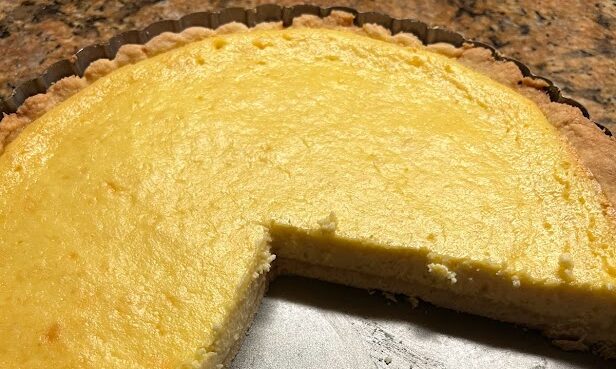

In Rome and Lazio, torta di ricotta often remains quite simple, sometimes blended with sugar, lemon zest, and cinnamon, then baked in a pie crust or as a standalone cake.

In Sicily, while the more famous cassata dominates Easter celebrations, baked ricotta torte (torta di ricotta al forno) persists as a distinct, rustic dessert. Typically, it involves a lightly sweetened ricotta filling, sometimes studded with chocolate or candied orange, baked inside a shortcrust pastry. Unlike cassata, it is straightforward and relies on the flavor of good-quality sheep’s milk ricotta rather than elaborate decoration.

In Tuscany, some versions of baked ricotta cake include a mixture of ricotta and ground almonds, a nod to the region’s medieval love of almond sweets. These cakes tend to be firmer and less sugary than southern versions, reflecting the northern Italian preference for more restrained desserts. ![]()