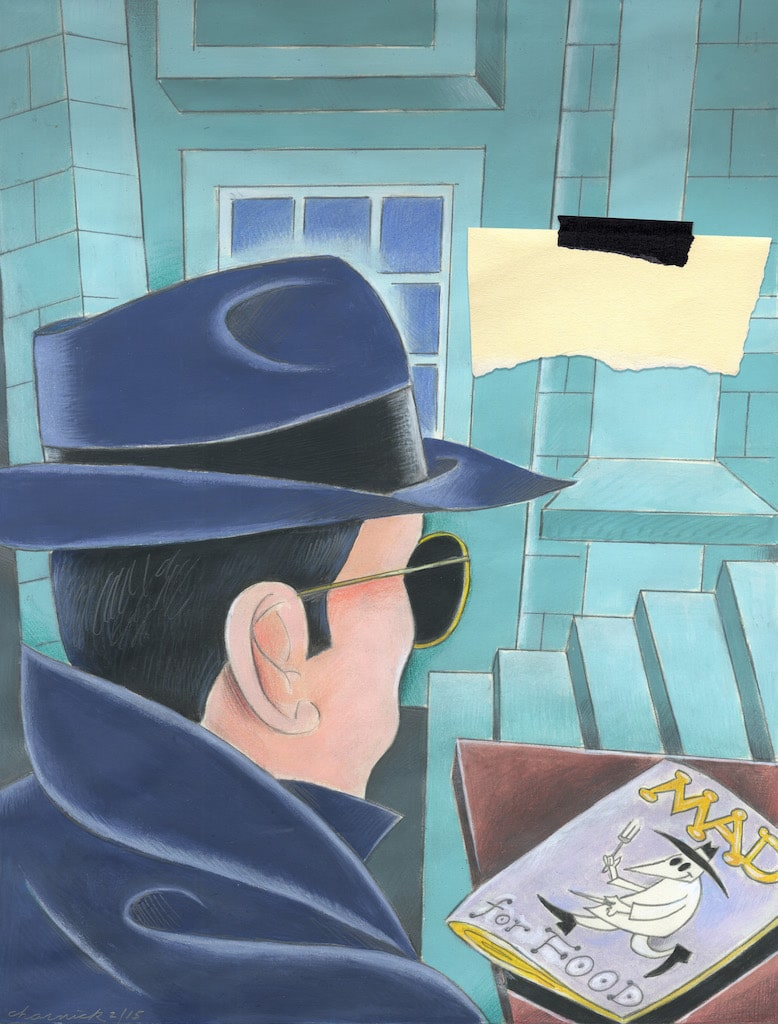

It was February 13th, the day before Valentine’s Day, and two strangers met in the bitterly cold and windswept shadow of a skyscraper in midtown Manhattan. After a brief exchange the pair walked down Seventh Avenue, turned the corner onto West 57th Street, and entered the foyer of Carnegie Hall. Security camera footage, were it reviewed, would reveal little. Two men, one in a black wool coat and scarf, one in a tan coat wearing dark sunglasses and a fedora; an elderly ticket woman in a tidy booth, if the camera were at an angle to peer into her miniature kingdom; a busker with a violin, performing with more enthusiasm than skill. The older of the two men would turn and face a stone plinth topped with an ornate art deco light fixture cast in brass, while the younger would snap a quick series of photographs of the back and side of his face. After reviewing the photographs and coming to an agreement with the other man, the younger man would appear to use his phone to send a message, to be followed by a short phone conversation, and both would leave.

It was as cloak-and-dagger an assignment as I’ve ever had, but the story, dramatically retold, is less Dashiell Hammett than one would expect. No secret codes were exchanged, no locations of Nazi gold were revealed. No lives were traded for previously withheld information, and no elections were bought or sold. In short, none of the things happened that one would hope would happen when a man in a fedora meets another for the first time on a busy New York street corner. This was the day that I, a person who scratches out a living by writing about things I put in my mouth and by uploading pictures of giant hamburgers to the internet, met Pete Wells, five-time James Beard Award-winning food writer and restaurant critic for the New York Times.

In pitching the idea of the interview to Wells, it seemed a golden opportunity to actually step inside the review process itself by asking if it would be possible to accompany him on a visit to review a restaurant. Somewhat to my surprise, Wells agreed and we set up a time and location, which also came with an email containing instructions. The reservation was made under a name other than his own; it would be ideal if we could try not to draw attention to ourselves; I could order whatever I wanted as long as it didn’t overlap with his own order, and the Times would be footing the bill. Also, we had to be done by 1:45: he had to pick up his kids after lunch.

It’s that last part that speaks volumes about Pete Wells. Restaurant critic for the New York Times may very well be the most coveted food job in the United States, if not the Western World, and one has to wonder about the person who bears the mantle. A wide range of restaurants are reviewed, but the bulk do seem to fall into the range of “$$$ to $$$$,” which is more than most are willing (or, these days, able) to pay. What kind of person then has this kind of life? What are the qualifications? Just how persnickety of a personality must one have to find fault with some of the most renowned restaurants in the world?

The answers to these questions may be surprising to some in that the job essentially calls for a normal human being who is knowledgeable about food and enjoys what he does. In fact, “I want you to get something that you’ll be happy eating,” was one of the first things that Wells said to me once we had been seated for lunch. Not the words one would expect from a man whose professional opinion can level proverbial mountains.

During the early part of our lunch I asked Wells about how the transition to restaurant critic had affected his life, and his answer was unintentionally funny in its simplicity. “The main thing about the transition from the last job is I don’t have to sit at a desk in the office anymore.”

Wells continued, “Do you know David Carr, the columnist who died last night? So somebody on Twitter was circulating something he said, you know, about how people going into journalism always did, and always still have to, pay their dues by working in grunt jobs for a few years for low or no pay, which doesn’t get better as you get higher. But you know, you start out with really no money and really inglorious jobs and going to town council meetings where they’re talking about whether they should repaint a crosswalk and you write it up and nobody’s going to read it except the town council… So you know, the path to success also has a lot of trudging along, particularly at the beginning. Carr said, ‘actually this is really good, it should be that way,’ because when you finally get where you’re going, you’re going to have a job where they allow you to get up from your desk and leave the office and wander around and go see the world, and then come back and tell everybody about it. And that’s a really great opportunity that should not come cheap. You should have to prove that you want it before you get that chance…so that’s how I feel about my job now. I definitely suffered at my desk for a long time and now I get to go out, really go out, into the city. You know, all kinds of neighborhoods and cuisines and styles of restaurants.”

Said Wells, “I do feel like I’ve been given this great privilege of really observing the city while eating and then telling people about it. And people, unlike at the crosswalk hearing, actually want to hear about things that I’m telling them. They’re really interested, weirdly, intensely, weirdly interested.” This is a side of Wells that comes out more than once during our lunch, and strikes me as being genuinely reflective of his thoughts on his job. I felt compelled to tell him that I, like most people interested in food, had read (and loved) his instantaneously thermonuclear review of Guy Fieri’s Times Square restaurant, Guy’s American Kitchen & Bar.

“I think there are a lot of fun food writers, and it makes it go down a lot easier, especially when it’s bad news,” said Wells. “I mean, I’m somewhat ambivalent about these bad reviews because you are having fun at someone’s expense. And yet, I think the alternative is worse, being super, super serious about it and acting like it’s a Supreme Court case that you’re trying. I mean it’s no fun for the reader, it’s never going to be any fun for the restaurant so you can just forget about that, but it’s certainly no fun for the reader. And so you always have the responsibility to keep the reader engaged, interested, and one of the ways to do that is to try to be entertaining. And then, with the Guy Fieri review, it just was just comically surreal. I mean, so many things about the place and the experience of eating there, just, like, you can’t believe [laughter]. This can’t be happening. It kind of called out for something out of the ordinary.”

What is striking about Wells is that even over the course of our roughly hour-long lunch he gives a strong impression of being genuinely friendly and engaged. It is not the view that many would have of someone who is professionally critical of others. When asked about whether it is hard to report that something is bad at a restaurant, Wells responded, “You know, what you have to do is figure out what’s bad about it. Why is this bad, why do I want to spit it out? Analyze that. Sometimes that involves taking multiple bites or even eating an entire dish of something that you know from the first bite is wrong. And you just keep going back to it.”

“I mean, there is a whole spectrum of ‘not good,’ from ‘That’s all right but I’m full and it’s not delicious enough to make me want it,’ to, ‘That’s revolting and I don’t want it anywhere near my mouth.’ And so, part of the job, and one of the fun parts of the job, is going deep on that unpleasant experience that most people would not care to analyze. Where the normal reaction would be ‘I don’t know, I don’t want to know, it was just gross.’ So if you’re going to say that something’s bad you’ve got to say why something is bad. You just have to, or at least you have to know, you have to know why it’s bad.”

This doesn’t exactly answer my question though. I reframe and ask about what it is like when something comes to him that is so improperly prepared that it becomes offensive. Ultimately, I’m searching for a glimpse into what it is like to be the vehicle of criticism. Wells responded, “Well, a lot of that would have to do with the context. So, how much money are you paying for it first of all. If, let’s say, you got an eight-dollar steak your expectations are going to be for an eight-dollar steak [laughing]. It’s like, you know, that’s ok for eight dollars. It seems to have come from a cow, and it was cooked. Whereas a sixty-dollar steak, or a hundred-and-twenty-, hundred-and-forty-dollar steak for two, had better be pretty perfect.”

“So then the slope gets very steep, where it can be not quite perfect but really pretty good. But then after that you start to fall off a point where just for this much money it should really be better. And then you also have, Why do we care about this restaurant, what’s the selling point? For me if it’s the chef, and the fame of the chef, I will expect a little more from the food.”

This is a question I had actually intended to ask of Wells: what are the expectations of restaurants run by celebrity chefs, and does their celebrity make it more likely that their restaurants will come up for review? Wells continued, “If it’s just a place that’s famous for being on the 39th floor, it has the best view in town but nobody knows the chef’s name, if the food is hot then great, you’re not going to throw it on the floor. But, if it’s a famous chef who spends a lot of time maintaining his or her fame and making sure you know who he or she is, [and] there’s a lot of attention going in to maintaining the brand, the food had better be good. Because that’s what they’re selling! What they’re selling is, ‘I’m a good chef.’ [That’s] something that we have to deal with a lot — more now than in the past — the restaurants where the chef is the whole selling point but the chef is nowhere to be seen because they have twenty-five other places.”

Without my specific prompting, Wells began to answer a question I had wanted to ask but had been afraid to bring up; namely, how do his emotional experiences as a diner influence his professional opinions? “Those places can make you a little indignant. The only reason you tricked me into spending my money is because you’re supposed to be a good chef, not because I liked your haircut. I’m not here because this is the place across the street from my office, or one of the [other] millions of reasons people go to restaurants…level of pretension factors in. If it’s a place that’s snooty or fancy, usually expensive goes with this. But, you know, a place that’s very, kind of, you feel like maybe you’re not good enough to be there, those places had better be perfect too. Because their whole reason-to-be is, you assume, because they’re superior. They’re acting superior, so they’d better be superior.”

Pete Wells, who goes to some lengths to protect his anonymity for the sake of an unbiased dining experience, addressed a fundamental feeling that a great many metropolitan diners have experienced at some point: that strange, unpleasant feeling of dining room inadequacy. My questions about the potential for personal bias at the hands of a reviewer have been answered. Put aside the fact that restaurants are visited more than once before a review is published, or that Wells is utterly qualified to dissect the food and service presented to him: for me, the true meat here is that despite his being an inveterate diner, and being truly, professionally justified in his participating in meals that some might describe as ridiculous in terms of both price and scope, he continues to have the same dining experiences as any of his readers.

Put aside the easily lambasted Fieri (it is low-hanging fruit) and instead see his takedown of Le Cirque, among others. Wells has a practiced eye, something easily observable during our lunch, but he also carries an everyman approach with him that seems to be amplified by his literary skill. He does not just observe, he conveys. When he reviews a restaurant he is specific and accurate, but he also entertains. At the end of the day, Pete Wells, restaurant critic for the New York Times and lauded food writer, is a man who no longer has to sit at a desk in order to do his job. So, the next time you’re on the street wondering where you’re going to eat, or standing in line at a restaurant for a table, bear in mind that the man standing next to you (most likely fedora-less) could very well be the most important diner in America. Right now, though, he’s just a guy leaving a work lunch on a cold, windy February day, so that he can pick his kids up from school. ![]()

First published April 2015