In the 1920s and 1930s in the United States, life before technology may have been simpler but cooking and housekeeping were difficult and time-consuming. Two books from that time period yield a lot of information about food and cooking, and also about women’s roles in general.

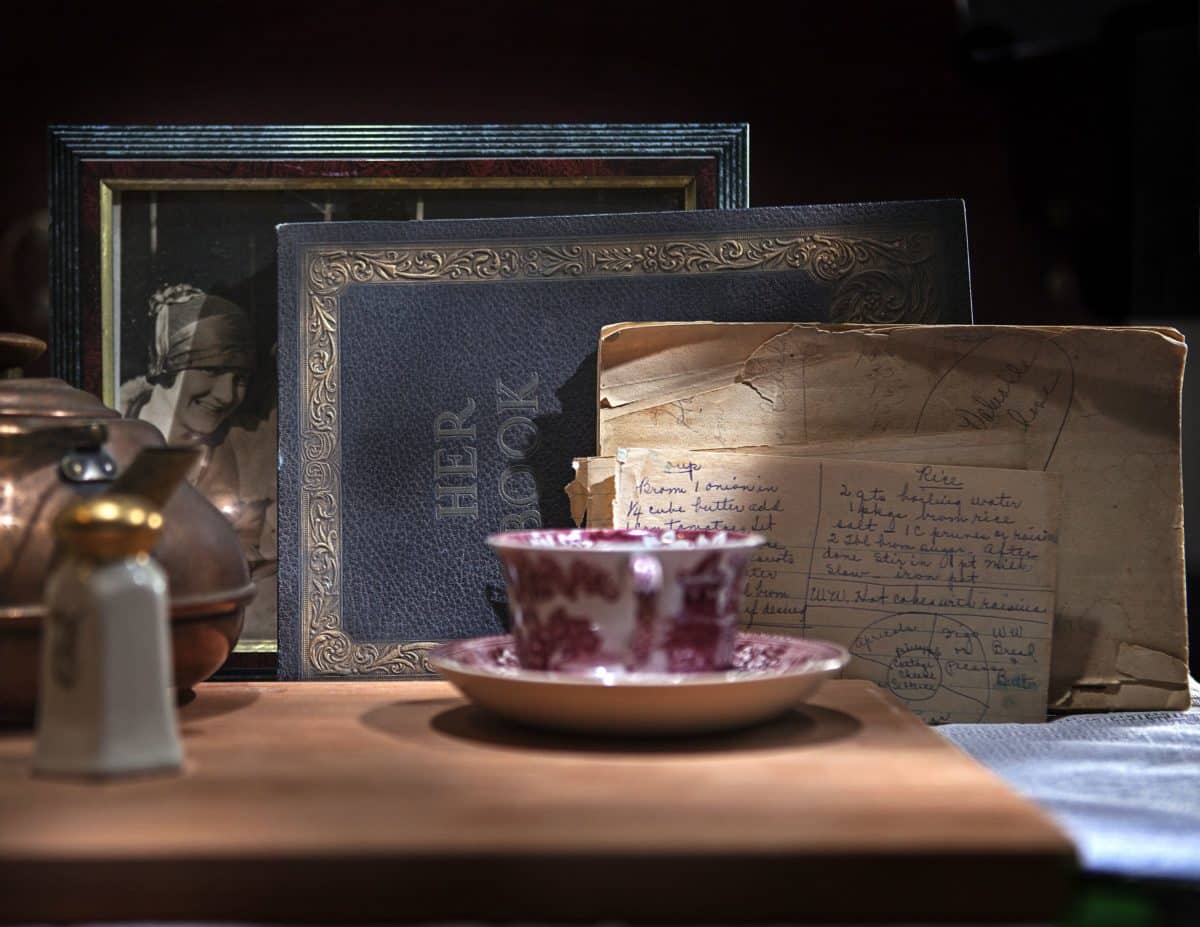

Books such as The Blue Stocking Cookbook (1923) and Her Book (1932) spell out how to cook savory dishes not often found in today’s cookbooks – for instance, Brain Croquettes and Rabbit Fricassee.

Recipes often lacked specifics. A review of The Blue Stocking Cookbook [“Choice Tried Recipes Collected by The Ladies of the Presbyterian Church of Marietta Georgia,” published in 1923] features recipes for a delightful “Cheese Sandwich” (“American cheese mixed with mayonnaise and greely sauce. Spread between thin slices of bread.”) There is no explanation for “greely sauce.”

Recipes from The Blue Stocking Cookbook feature ingredients rarely seen in most American homes today. Baked Tongue features the tongue baked in a casserole with onions and tomatoes, but doesn’t give the required oven temperature. It fails to mention what animal gave its tongue for dinner, although presumably it was a cow. Similarly, a recipe for Chafing Dish Birds doesn’t mention what type of birds go into the chafing dish, but includes instructions to “Prepare birds overnight. Split down back.” Cooks in 1923 must have understood what would be needed but in 2018 it’s a mystery. A recipe for “Scraffle” begins “Boil a fresh killed hog’s head tender. Take it up and remove all the bones.” Delightful.

None of the recipes give oven temperature or cooking time. Presumably, in 1923 many women would have used a wood burning stove for cooking and that likely accounts for the lack of specifics.

Recipes from The Blue Stocking Cookbook are intriguing as well as confusing. For instance, a recipe for Tomato Catsup calls for tomatoes, apple vinegar, salt, sugar, mustard [“an entire small box”], black pepper, cayenne pepper, three “good onions,” and this mysterious ingredient: “1/2 handful of peach leaves.” One must boil it and sieve it, and then there’s a sinister instruction: Seal and keep in a dark place. (Possibly next to the freshly killed hog’s head and dead birds?)

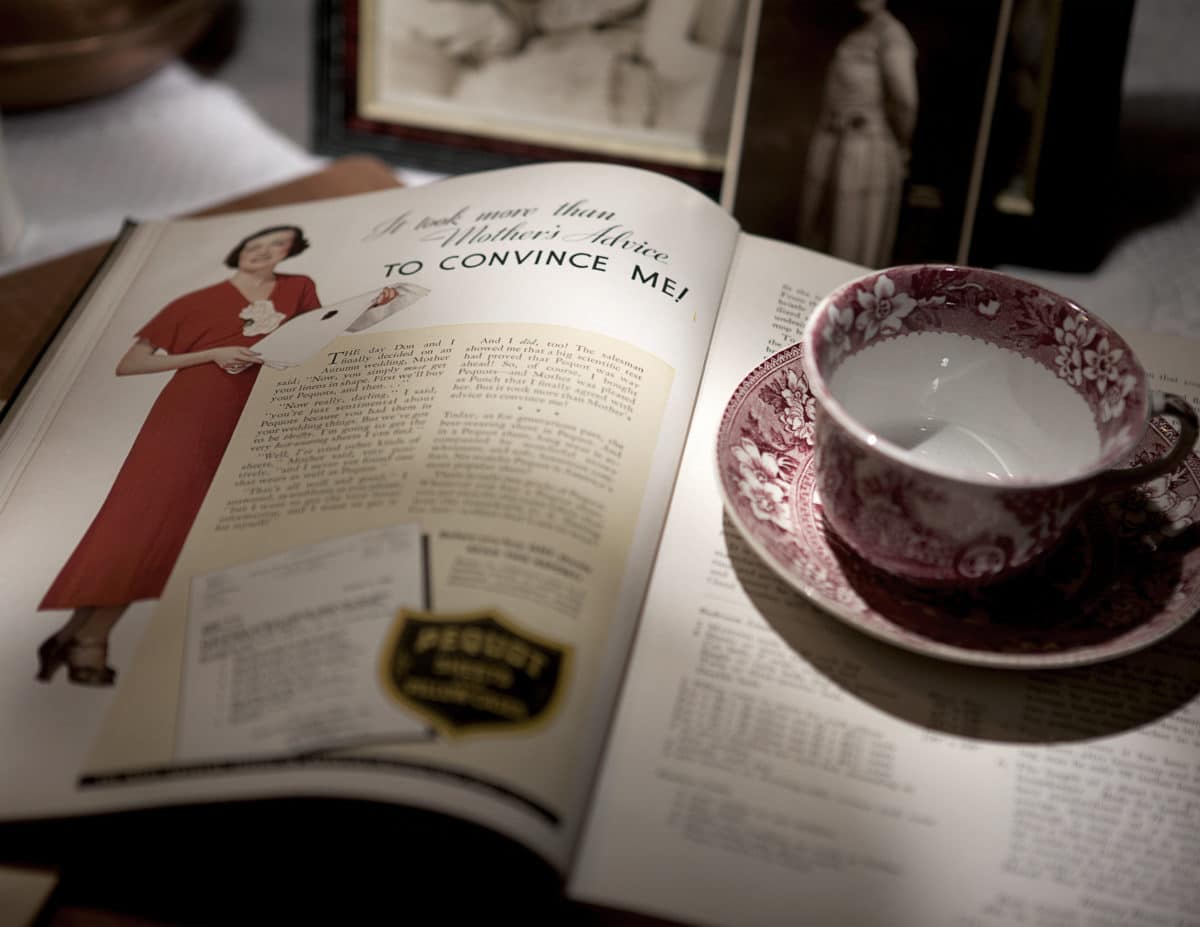

The ads in The Blue Stocking Cookbook appear rather droll to a twenty-first century reader. Wallace Candy Kitchen’s ad notes “Pure Candy Never Hurt Any One” and it exhorts the reader to “Let the children eat all they want.” (Perhaps a dentist owned Wallace Candy Kitchen?) There is no address or phone number for Wallace Candy Kitchen. Presumably it was in Marietta and everyone reading the book knew where it was located.

The full page ad for Snowdrift solid vegetable oil touts its health benefits – “It is rich, nourishing wholesome food – 100 per cent pure fat… itself more nourishing that (sic) almost any food you cook with it.” It was probably more healthful than the lard commonly used in those days.

Swans Down Cake Flour purchased the only color ad in the book, featuring a drawing of a birthday cake decorated with green leaves and pink roses atop the icing, and claiming “You can have lighter, whiter, finer, better cake – pie crust – pastry, just as you long to have it.” Also, “It saves all the costly waste of cake disappointments.” As noted, in those days, cake baking was hit or miss, with ovens that were hard to heat and regulate.

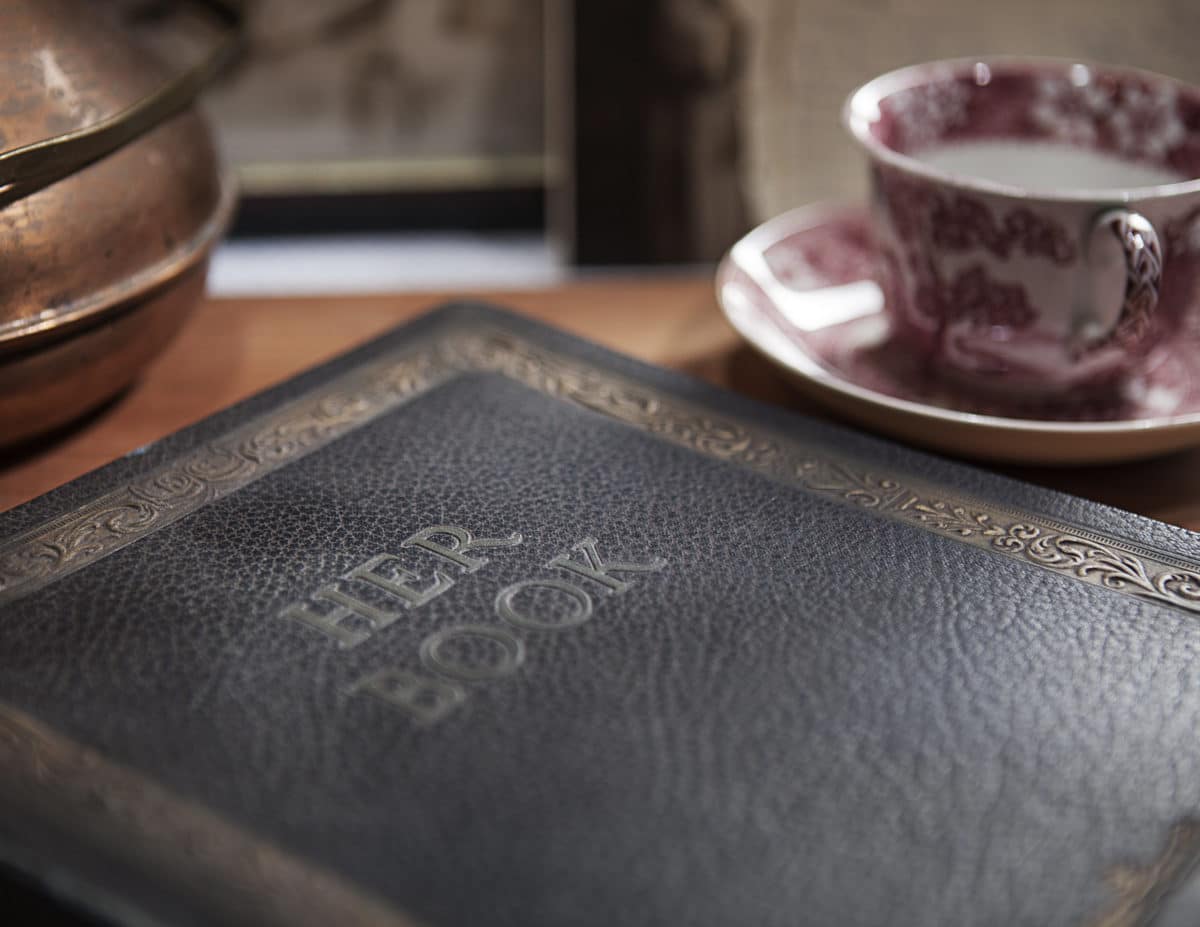

Her Book, A Treasure of Household Lore, published by the R.M. Travis Corporation in 1932, is a far more sophisticated guide than the little Blue Stocking cookbook, and includes more housekeeping advice and standardized recipes, with actual measurements and oven temperatures noted.

It contains articles like “The Importance of Refrigeration.” Clearly there was debate back then, to refrigerate or not? Of course, most folks likely had “iceboxes” – just insulated boxes that required large blocks of ice below them to keep foods cold. (To the end of her life, my grandmother always referred to the refrigerator as the “icebox.”)

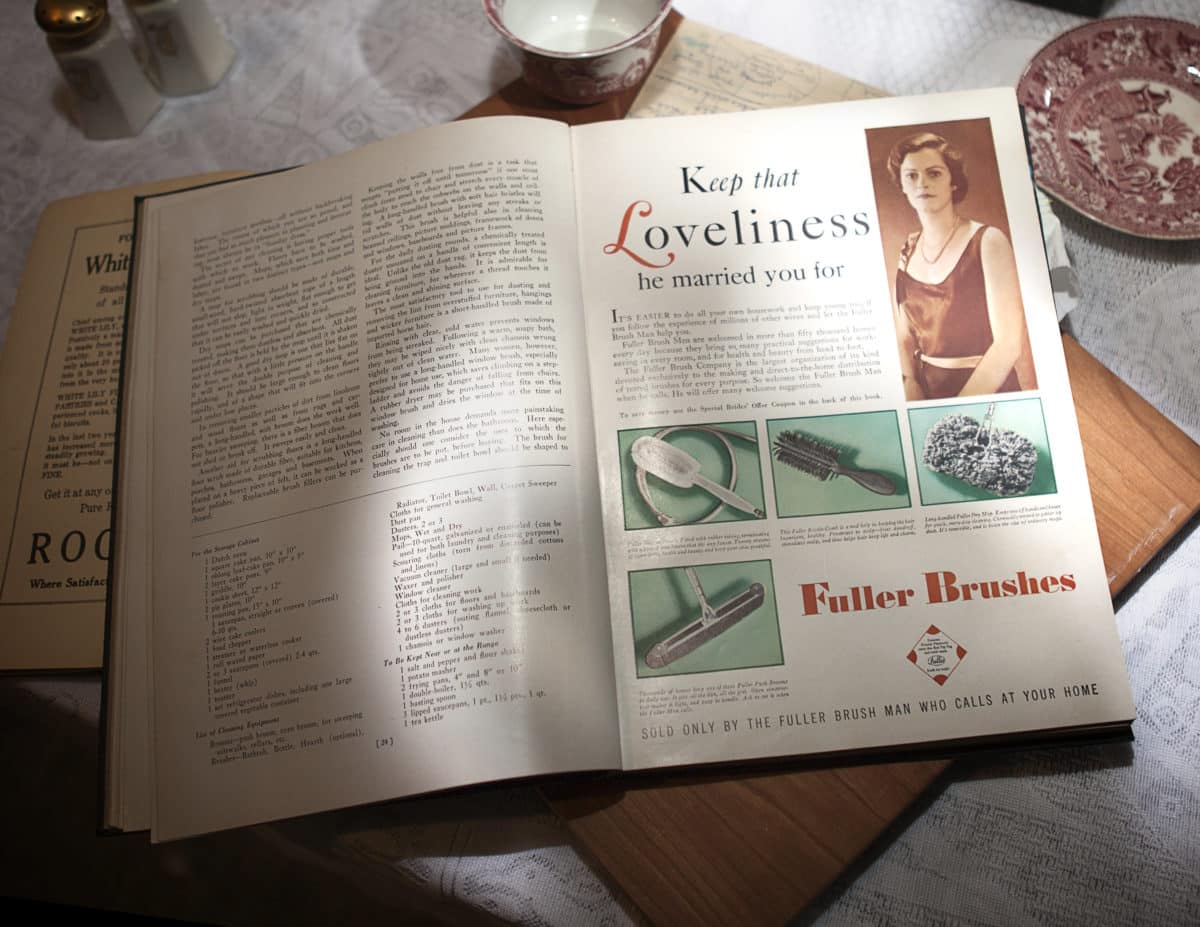

Her Book is a time capsule. Anyone majoring in Women’s Studies in college, or studying history from a feminist perspective should spend some time looking through a book like this. Implicit in all the instructions are the ideas that keeping a clean house and being a good cook are the highest accomplishments a woman can hope to achieve, and the conviction that cleanliness will sustain a marriage.

The Preface infers that if a woman keeps her house clean she won’t ever get divorced, noting “…when the bride has begun to look upon her household as a fascinating hobby with endless possibilities she has mastered the first big secret; she is ready to try out the recipes for happiness which follow.” No specific recipes for “Happiness” are included.

Leftovers are sure to drive your husband away. A full page color ad for Crisco contains recipes for Sweet ‘Tater Puffs, Prunella Cake, and Good-Bye Shortcake. The ad copy begins “You have my sincere sympathy if your husband looks scornfully at cold meat and warmed-up vegetables. A man’s just like that!”

In addition to recipes, there’s a chapter called Modern Improvements in Laundering. It includes instructions on how to get out stubborn stains using a washboard as well as a washing machine. At a time when bars of homemade laundry soap were still common, Her Book touts the far superior qualities of “granulated soaps.” There’s also a bossy tone, as in “Fifty-two times a year a family’s soiled clothes have to be washed. Some one (sic) must make them fresh, crisp and clean before they can be worn or used again.” There are rules for washing whites, cottons, silks, rayons, diapers, woolens, colored clothes, and blankets. Dryers were not invented yet, or perhaps were not common, because there are three paragraphs about how to dry clothes on a clothes line. About a thousand words explain how to buy a washing machine.

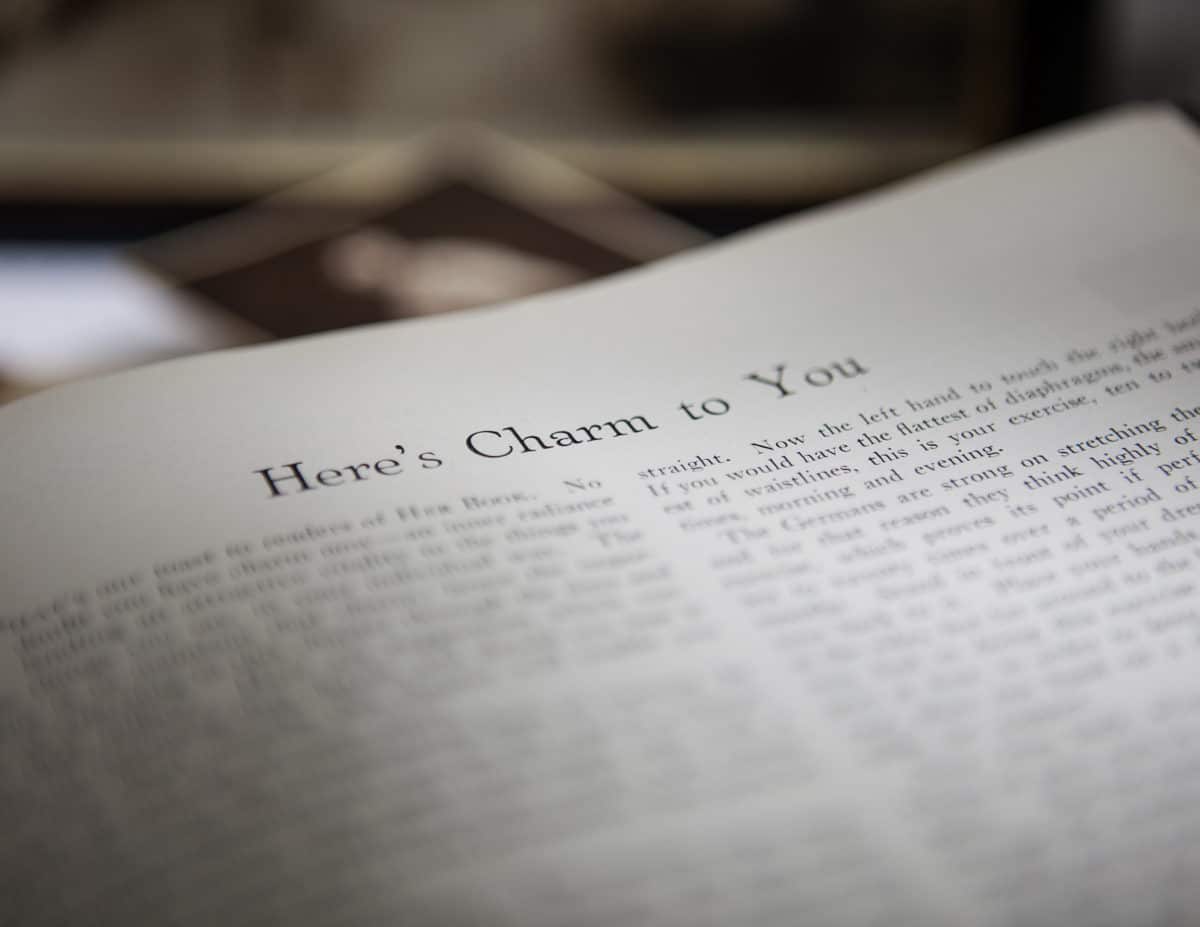

All aspects of domestic life receive thorough attention. Some chapters cover how to wax a floor, how to care for electric lights (“Lighting Has a Charm All Its Own”), Interior Decoration as an Art, and a chapter called Here’s Charm to You. Charming women understand the importance of exercising, and it suggests several exercises invented by the Germans and Swedes which should be done daily, and are suitable even for women who are lazy. “Suppleness and limberness will give you lissomness” it suggests. (Unsurprisingly, muscles are not advisable, but flexibility is very important.) Several paragraphs contain instructions on how to properly take a bath. A section entitled Why Not Use Deodorants? favors their use, and warns “Total or partial disregard of a deodorant means overstepping the bounds of personal liberty.”

The most fascinating chapter of Her Book is titled Standards of Social Etiquette. It reads as though written in 1832, not 1932. Rules for “paying calls” and the use of formal “calling cards” are explained in detail. Women were expected to stay home one day a week to receive visitors, and to put their “at home” hours on their calling cards.

Women were always referred to by their husband’s name – Mrs. John Jones, for instance — and that continued even after the husbands had died. Introductions were formal and strictly regimented. Women were supposed to introduce their husbands by their last name, such as “Mr. Brown,” with first names only mentioned to close friends.

It’s hard to envision but in 1932 the handshake was a bold innovation. “A courteous acknowledgement of every introduction is essential. The stiff, formal bow is losing prestige, and the warm, cordial handshake is taking its place.”

At a time when most of us have no idea how to prepare a dead bird for dinner or wash clothes on a washboard, it’s fascinating to remember how much more complex life was in 1923 and 1932, before the widespread use of electric lights, electric refrigerators, and washing machines. We are thoroughly spoiled by oven temperature gauges, refrigerators, and the widespread convictions that everyone should shake hands and wear deodorant. ![]()