A reminiscence from 2015 about a memorable afternoon.

I had been preparing for this moment for weeks. Books and articles had been read, notes taken, internet videos watched. I’d sought inspiration for questions from a select group of friends, both in the restaurant world and outside, who were sworn to secrecy. The trunk of my car held everything I thought I would need – a well-worn copy of his autobiography; interview questions (neatly formatted, blocked inquiries and notes scrawled hastily during a short break at a dilapidated rest stop in Delaware); my camera and tripod; and, lastly, a gift for the chef of a growler of Washington D.C.-brewed beer and a cheese pairing. In short, I was ready.

And suddenly he was there, opening the glass door of a screened in porch, with a painting on the wall beside him that read in curling script, “Gloria’s French Café,” welcoming me into his home.

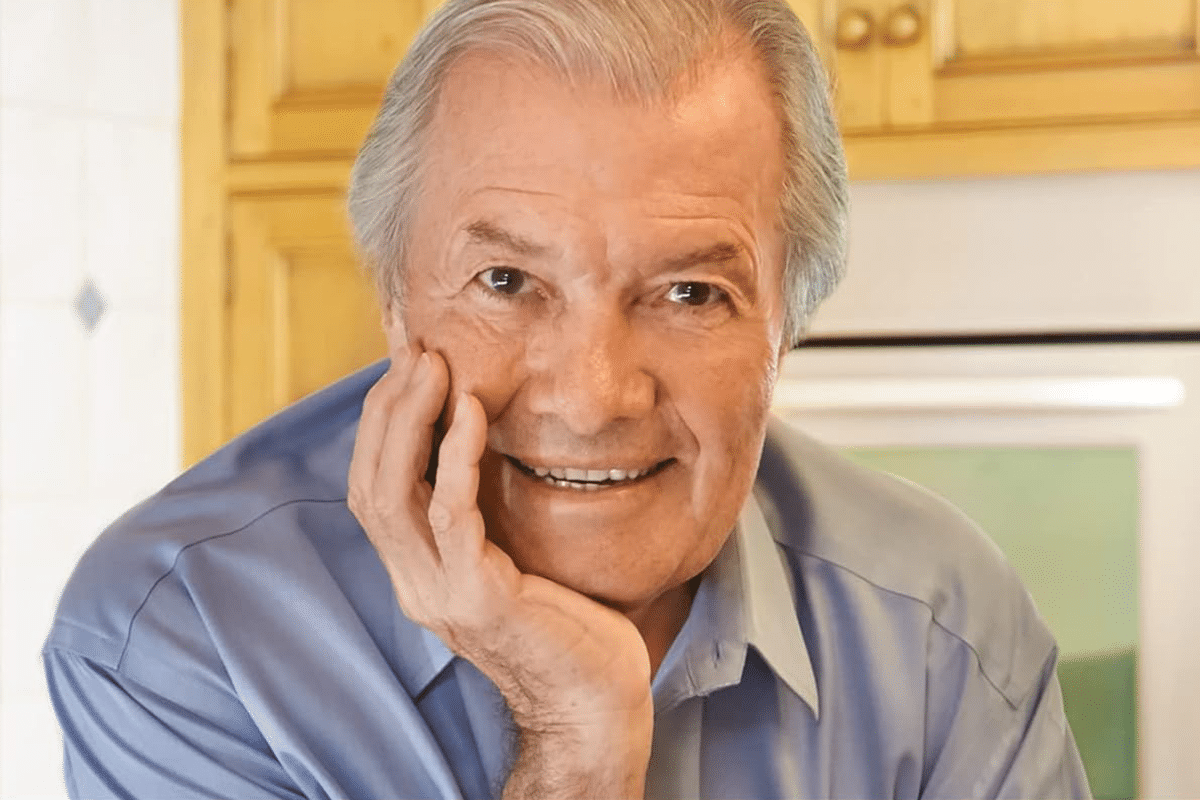

“Hello, I’m Jacques Pepin.”

Jacques Pepin was the first food celebrity I ever saw on television, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that he is among the most famous, influential, and well-regarded chefs of the past century. Born into a family of restaurateurs, he is internationally recognized as one of the most accomplished chefs in the world. Honored by his home country of France at the highest levels and by his fellow chefs as a recipient of multiple James Beard awards, he is a chef, author, teacher, and artist. He is a grandmaster of his craft, known for his incredible technical skill and knowledge and his ability to teach others in a variety of formats, be it in the classroom, via text, or on television.

And yet, despite having run multiple successful restaurants, written an array of cookbooks, and numerous other achievements (which include being the personal chef of three French Presidents, including Charles de Gaulle, and an invitation – which he declined – to be the Executive Chef at the Kennedy White House), he is friendly, welcoming, easy-to-engage, intelligent, insightful, and humble. In short, not exactly what one would expect from a champion in a profession now made famous by people whose prodigious skill is matched (and sometimes even exceeded) by the accompanying size of their ego.

“I started in that business in 1949,” he said while we sat on the back patio of his home in Madison, Connecticut, “but at that time, and even up to thirty years ago, forty years ago, the chef was at the bottom of the social scale, and any good mother would have wanted her child to marry an architect, a lawyer, a doctor, certainly not a cook! Now, we are ‘genius.’ So it is quite different from how it used to be.”

Even now, after the interview is finished, it is not lost on me that this statement is not just a mild criticism of the phenomenon of the “celebrity chef,” but also an observation, as there is truly genius to be found. This is where a key element of the charm of Chef Pepin lies. While he spoke with some regret about the impact that the culture of celebrity has had on contemporary culinary students (“Now, two out of three, or certainly two out of four or five students, when I am at the school in New York or in Boston, want to talk to me or have an exit interview. Usually the first question is, ‘I have a great idea for a book, I have a terrific idea and want to have a television show.’”), he maintains a gentle but persistent optimism. This optimism also seems to be directly related to his own experiences with the gradual rise in professional status and freedom of expression that chefs have come to enjoy.

When asked whether he thinks that the phenomenon of the celebrity chef could be related to the American tendency to elevate people into positions that carry public prestige or fame, he replied, “Sure, no question about it, that’s America,” but followed with the statement, “If I had stayed in France – and I’ve been here over half a century – I would not have gotten where I am [in the USA]…and I certainly would not have gotten the knowledge of cooking, and I’m talking about the knowledge of ethnic cooking. It’s interesting enough, because people see me more often than not as the quintessential French chef, and then I open my book, The Essential Pepin, and on page twelve I have black bean soup with banana, which came from my wife being Cuban, and then on the next page I have fried chicken done in the Southern style, which I never did in France. And then you do have French recipes as well, certainly!”

Having read Chef Pepin’s autobiography, The Apprentice: My Life in the Kitchen, this was something I was very curious about. When one has lived in another country for so long, do they become of that place? Is it possible to become ingrained with the customs and habits of the place you live, while still being true to where you are from? In his autobiography he wrote about various expatriates he has known through his life, but it is one thing to describe someone you are friends with and another to speak about how you view yourself. Ultimately, my worry over my curiosity was unnecessary. Said Chef Pepin, “After so many years that I’ve been here, I am not trying to be French in what I do, but by the same token I am not trying not to be French in what I do. I don’t think in those terms at all: I cook, I get an idea somewhere and it may be more of this or more of that, and that’s a very American attitude in that sense. So in that sense my cuisine is probably pure American cuisine! But yes, it is another world, a world I certainly would never have entered if I had lived in France all those years.”

To the benefit of all those who follow him, Chef Pepin continues to work, to teach, and to plan. “We will be shooting a new [television] series in the fall, I guess probably September or October, so it’s 26 new shows and a new book. I have a great deal of my artwork in it. So that will actually be the 13th series of 26 shows that I do with KQED, the PBS station…25 years that I’ve been doing shows with them. And then after that, my last series, which it probably will be!”

It was an unexpected statement from a man who has done so much, and who continues to be so engaged and active in his career. Said Chef Pepin, “Well, I have to give my book and do my series at the end of the year, and then it will come out next fall, and that will kind of coincide with my 80th birthday. I mean, I may do a show here and there, but…”

The truth is that it is easy to forget that Chef Pepin is as far along in his life as his birthdate makes him. Initially it is almost a shock to hear him speak about his childhood in France, which took place during the Second World War, and of the fragile years following the war’s end. Chef Pepin, who served in the military in more than one posting as a chef, spoke of his frankly awe-inspiring experiences matter-of-factly, and with humor. “When I worked for the French President [Charles de Gaulle] I served people like [Josip Broz] Tito, [Jawaharlal] Nehru, [Harald] Macmillan, whoever was head of state at the time. You kind of tried to sneak a peek, but you would never be allowed in the dining room or have anyone coming to see you. If anyone came to the kitchen something was wrong, and you’d better watch out!”

Abandoning my interview questions, I asked Chef Pepin if he felt that he actually needed to retire, or if there was room to continue to work past the point where others in different professions would normally stop their work. His reply was, “For us, it’s great. It gets even better as you get older, I mean it seems. I think it was Jean-Paul Sartre who when someone asked ‘what is your best book?’ said, ‘my best book is the one I’m going to do next’. You can never think that you’ve done your best.”

The influential developmental psychologist Erik Erikson wrote that in the later years of life we look back on our accomplishments and weigh the impact they have had, with two possible outcomes. For those who have lived a life devoid of purpose: despair. But, for those who have been happy and productive: integrity. By almost any measure it can be said that Chef Pepin has reached the latter stage, and despite his words, and encouraged by his tone, I have hope that his upcoming series will not signify the end of his public career. Serious, but still smiling, Chef Pepin said, “But yes, in our world, you know, of living people, you get old. I’m old now, but yet, I’m not a star in Hollywood, and so I don’t have to keep my figure and my face. I can keep cooking if I get older and fat, or whatever! So yes, for us it is good.” ![]()