I’m sitting with Garrett Oliver in a small conference room at Brooklyn Brewery, where this year he is celebrating his 20th anniversary as its Brewmaster. In the adjacent room, several members of his staff are waiting for him to finish speaking with me so that they can begin a meeting. However, even knowing that his time is precious and that I’m beginning to inconvenience a number of people who have been very nice to me since I arrived at the brewery, all I can think is, “I wish I had more time to talk to him.”

Garrett Oliver is someone you want to spend time with. I first met him at Savor, an event billed as “an American craft beer and food experience.” He was co-hosting a salon about collaborative brewing and the influence of art and music on the brewing process. Then, as now, he was both well-dressed and well-spoken, and also pretty trim for someone whose life is centered on the production and consumption of beer. In fact, there are a variety of ways that Oliver could be described – intelligent, articulate, and engaged are just a few. However, the single best word to describe him would probably be “worldly.”

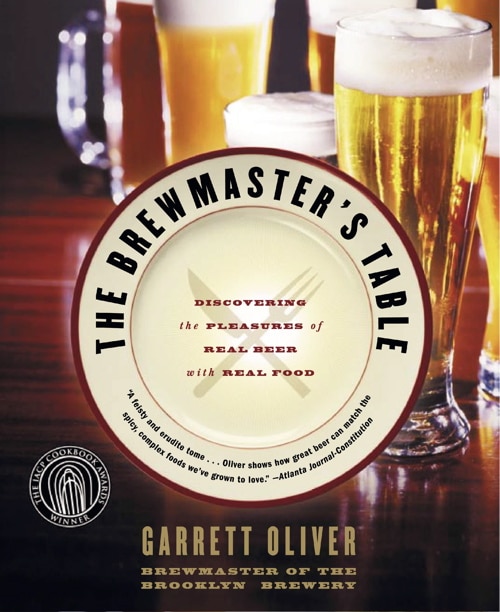

Oliver knows quite a bit about a wide variety of subjects, but it’s his ability to use enthusiasm and humor while speaking about his own experiences that makes his stories sing. Once a film maker, he has also worked for a law firm, stage-managed rock bands in London, and is the author of several books, including the incredible Oxford Companion to Beer and his sleeper hit about food-and-beer pairing, The Brewmaster’s Table. He is also the first beer professional in history to win a James Beard Award, which was given to him in the category of “Outstanding Wine, Beer, or Spirits Professional.”

What’s striking about speaking with Oliver, though, is his tendency to look directly into the eyes of whomever he is speaking with, and the easy air with which he speaks about topics both related and unrelated to beer. When asked about The Brewmaster’s Table, Oliver said, “It’s a very different book than the Oxford book because this is a book that was basically burning a hole in my pocket, like, you know, it’s a polemic in some ways. I had a lot of things I wanted to say, and one thing that I saw was that beer people often didn’t seem to know or care that much about food, and food people didn’t seem to know or care that much about beer.”

Oliver, one of the few people I’ve met who can accurately be described as a renaissance man, spoke with enthusiasm about the potential for pairing food and beer. “Wine was the beverage that was generally applied, when it was fairly obvious to me that wine is a far less versatile beverage with food than beer is. And that’s not a criticism of wine, I love wine…but [with beer] we just have an awful lot more to work with. We can caramelize our grains, we can roast them, we can smoke them. We can basically make beer that tastes like anything. Wine has one ingredient, grapes, which is an awesome ingredient, but that’s a pretty damn big limitation, you know, when it comes to looking for versatility.”

It is this observation about versatility and the ability to pair beer with food that seems to be a cornerstone upon which Oliver has placed a large portion of his career. Oliver and the Brooklyn Brewery have hosted a number of food-and-beer pairings and events, and it is the resulting knowledge and experience that have led to the development of a formal brewing program at the Culinary Institute of America, also known as the CIA.

“I eventually went professional in 1989 because beer had basically taken over my life, it became an obsession.” – Garrett Oliver

Said Oliver about the brewing program, “We’re working it out right now, but on a physical basis it’s a seven-barrel brewery, so pretty small, but, you know, it’s the size that most brew pubs start with traditionally. It’ll make about fourteen kegs at a time. That beer will go to the campus restaurants, of which there are several. There has always been a very active sort of beer and brewing society at the CIA, so they’ve always really been into it, but it’s only been in recent years that they’ve started to put any thought into beer education.”

Education is a significant piece of Oliver’s personal mission as the Brewmaster of Brooklyn Brewery. “And now the situation has started to turn around where they – and I think not only they, but many other big schools – are finding that if you send someone through a cooking education and a beverage education and out into the trade, and they’ve had weeks and weeks and weeks of wine training and only a day or two of beer training, they show up on their first day completely unequipped to do their jobs. I would say that beer – I think this is an important point – beer is the only area that I’m aware of in food and drink where it is totally common for customers on average to know more than the staff at the restaurant about the things the restaurant is selling. That should never, ever happen.”

To understand Oliver’s passion about preaching the word of beer, it’s helpful to know a bit about his own background and how he began what is now an illustrious career in the world of beer. “It’s 25 years of doing this. Of course, when I started out, you know, first I was a home brewer starting in 1983 or 1984. I lived in England from 1983 to 84 so I was there for a year. I was stage managing rock bands and I would go to the pub and I discovered this stuff called ‘beer’…and I had been to college and I thought I knew what beer was, and I thought I knew what cheese was, and I thought I knew what bread was, and in those days bread was basically like this white chemical sponge that came in a bag, stayed fresh for two weeks. You know, [in the USA] Wonder Bread was the best known brand of this stuff, and that was bread. Sure, I’d see a good Italian loaf every once in a while, but pretty much that was bread. There wasn’t a bread aisle, there wasn’t a cheese aisle – there was Cracker Barrel, there was Kraft Slices…so no cheese section. And beer was a thin, fizzy yellow liquid that ranged between flavorless and nasty. And the flavorless stuff, as far as we were concerned, was the good stuff.”

The Brewmaster’s Table was first published in 2003, well in advance of the stunning craft beer vanguard that is now changing the face of beer across the world. This is interesting because it shows that Oliver was ahead of the curve by over a decade. It also speaks to the importance of the era though, and how his experiences as a young person with very little choice forced him to be the architect of his own success.

Oliver continued to speak about his college years by saying, “Frankly, we bought Budweiser when we had money. At least it tasted like water, you know, it was neutral. And so when I got to England and discovered this beer that tasted wonderful I was like, “Wow, this is great!” and then I went all over Europe and I was like, “This is even better! This is tremendous!” And then I got back [to the USA] and it was a year later and [in the bars] they said, ‘Bud, Bud Light, Miller, Miller Light, Coors, Coors Light…Heineken.’ And you know, maybe you could find a dusty old bottle of Guinness somewhere.”

Laughing, Oliver said, “And I was like, ‘Oh no, my life is over when it comes to tasting things!’”

I asked Oliver if this contributed to his start as a brewer, a suspicion which he confirmed. “My point is that I wasn’t interested in making beer – it was the only way to get any. You can imagine if you had been to France and had spent a year there and you ate great bread and great cheese, and you got back and there was nothing but Kraft slices, you might think about cheese making, you might think about baking your own bread. For me it was the same sort of thing.”

The comparison between food and beer, between established food supplies of questionable quality and the rediscovery by dedicated specialists, is a platform upon which Oliver has become a modern-day prophet. Unlike a prophet, though, who may speak in riddles and who rarely has substantive information, Oliver approaches his positions as both a craftsman and a businessman.

“Supermarkets, like restaurants, have figured out that the craft beer drinker is a valuable customer. If you are a supermarket that does not have a great craft beer section, you are going to lose the guy who would actually spend more money for steak, and for cheese, and for bread, and for everything else. You’ve lost the high-value, high-margin customer. You’re still going to have people going in there buying toilet paper, but you’re not going to make any money. So, the same thing happens in restaurants, and I don’t think that people realize that when you go into a restaurant, even if you’re not a beer fan you look at the taps…you think you’re not paying attention, but you are. And if you see kind of industrial-looking beer across all the taps of the restaurant, somewhere in the back of your mind you’re not going to order the fish, you’re not going to order the most expensive stuff, because you no longer believe these people are switched on. They don’t seem like they’re with it, they don’t seem modern, and you no longer believe they can really cook this food.”

It is dedication and passion that drives Oliver, as well as many others in the world of beer. Asked about what propels him forward, Oliver said, “I think it’s a passion about the work, I think it’s endlessly interesting, like cooking. We take so many inspirations from everything…other beers, cocktails, wine, even music.”

Oliver also spoke about what it’s like to be recognized and to produce a product that is visible and well respected. “I have friends who are rock stars, like legitimate rock stars, who can walk into a place around here [Brooklyn] and hear their music playing and they’re like, ‘Yeah, it’s pretty cool!’ and that’s the way that I feel when I walk into a bar.”

Finally, I asked Oliver about what he says when people approach him, as they do regularly, about their own desire to brew professionally.

“I talk to people who say, you know, ‘I’ve got a family, I have a kid, I’m 35, I hate my job, I’m miserable every day, and all I want to do is brew, and, like, do you think I should take the leap?’ And it’s a very hard thing to say to anybody because you’re like, well…I can’t dispense to you financial advice. I can give you a little bit of family advice, though, and I think my belief is that as long as you get enough food on the table for the kid and keep him in shoes, whatever else, a 3-year-old is never going to remember that they didn’t have the very best of everything or that things were touch and go for a while. They will remember however if they had a happy dad, who was doing what he wanted, or if they had a miserable dad. So maybe that’s your choice.” ![]()