I don’t have to be trapped in a Star Trek rerun to affirm that historical cookbook collections can enable time travel.

My own chrononautic trip was fueled by Indian Pudding. And it launched and landed myriad times between 1772 and 1960 in the reading room of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives at Bowdoin College Library in Brunswick, Maine.

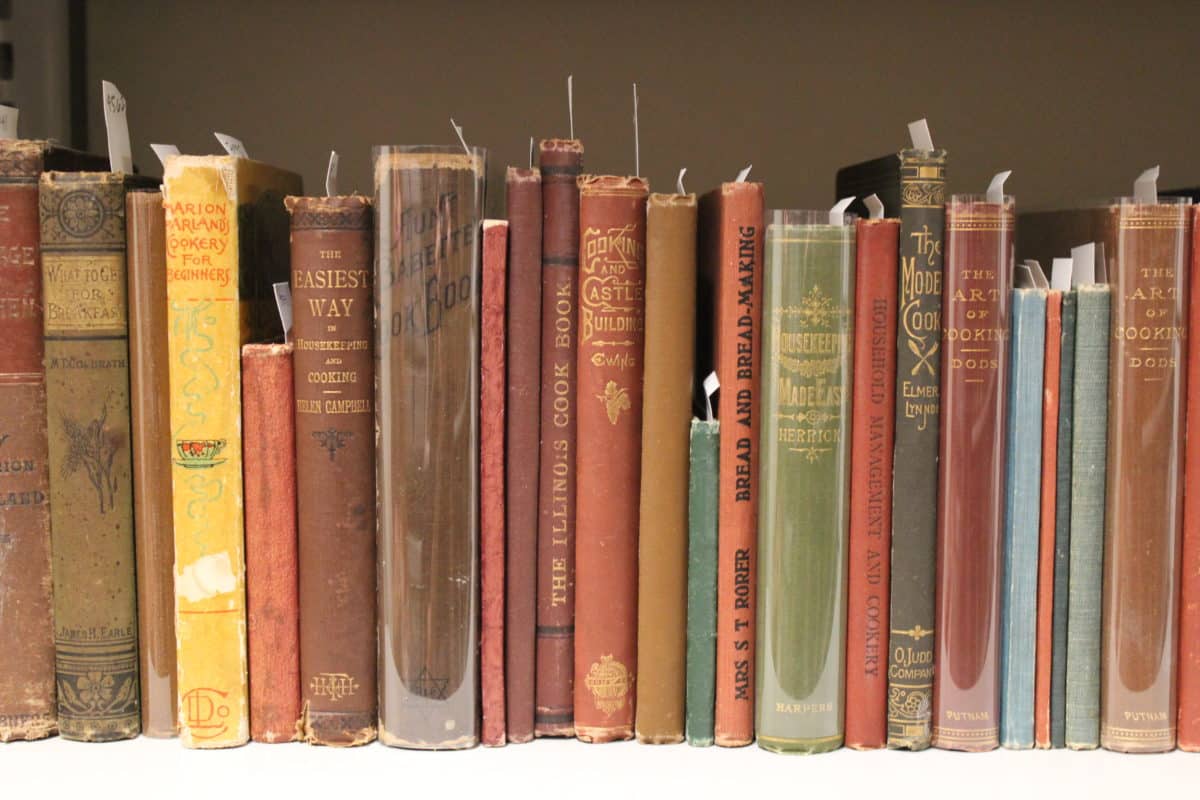

In September 2015, Esta Kramer, a former editor at the New York-based Arts Magazine who now lives in mid-coast Maine and has a keen interest in food, cooking, gardening and cookbooks, made a generous gift to the liberal arts college to purchase a collection of over 700 American cookery books. Bowdoin agreed to house the collection in its entirety and keep it open to the general public – both conditions of sale set by Clifford Apgar, a retired banker from upstate New York who amassed the collection over decades. Apgar connected with Kramer via rare cookbook dealer Don Lindgren, owner of Rabelais Books, a shop physically based in a refurbished mill on the Saco River in Biddeford, Maine, but known worldwide for the antiquarian culinary works that flow through it.

The oldest cookbook in the Esta Kramer Collection of American Cookery, Susannah Carter’s The Frugal Housewife, published in 1772, had no receipt (the word used for recipe until circa 1888) for Indian Pudding. No surprise there. Carter is a Brit and Indian Pudding is a truly American dish – sometimes served as a side, sometimes as a dessert, always made with cornmeal, molasses and milk. This edition of Carter’s book, printed in Boston, was merely a copy of her best-selling English one released seven years earlier in London and Dublin.

As I was turning the pages of an updated edition, this one reprinted in New York in 1795, I found a pressed four-leaf clover amidst Carter’s monthly menu suggestions for February (she suggests a saddle of roast mutton with pickles and a brain-laced parsley sauce, if you’re curious). I was lucky enough to find Indian Pudding listed in the index. But on the referenced page, the receipt given was for Italian Pudding. An unfortunate typo, for sure.

The Indian Pudding receipt didn’t make Carter’s cut until 1803, when the book was reprinted again, this time with an appendix that honed in on colonial cooking using common American ingredients like maple sugar, pumpkin and cranberries. This edition is not in the Kramer collection. I found it online, and could see the recipe, but the computer screen did not offer the same level of temporal transport.

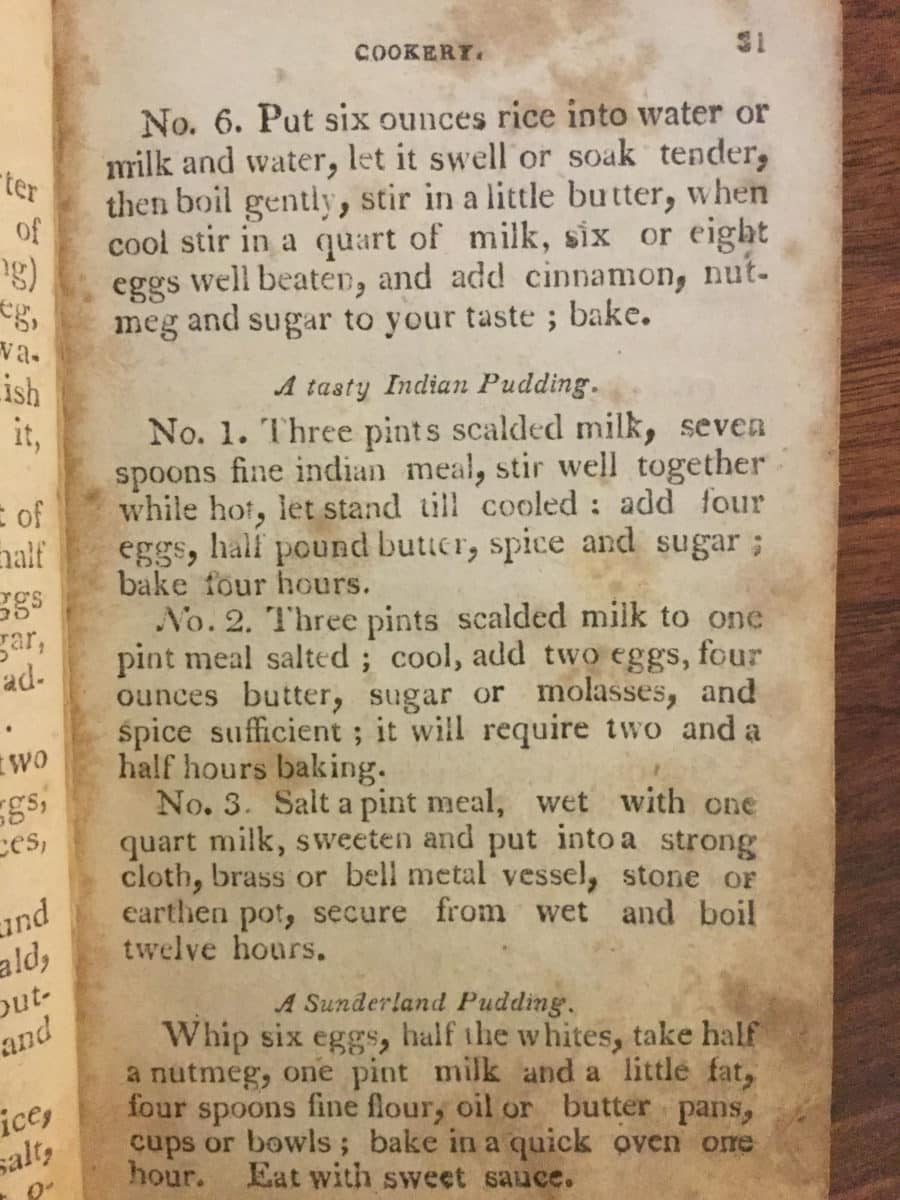

Another English cookery writer, Hannah Glasse, in her 1805 edition of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy printed in Alexandria, Virginia, has two Indian Pudding recipes, one steamed as was the English tradition and one baked slowly in a warm – but not piping hot – part of the open hearth used in colonial kitchens. These receipts — one takes up only four lines, the other six – called for Indian Meal, because it was Native Americans who had introduced ground, dried corn as a wheat flour alternative to the colonists.

The collection also includes an 1815 hard-cover edition of the first truly American cookbook, American Cookery, initially published in 1796 by “an American Orphan,” who was later named as Amelia Simmons. According to Lindgren, there is an unverified story explaining that Simmons crafted the book to help other orphans succeed in a life of domestic service even though she lacked a mother who could teach her to cook. Simmons totally tarted Indian pudding with the inclusion of sugar, eggs and raisins to make her mark during an age of recipe writing that was largely plagiaristic in nature.

I had to go south via an 1824 copy of Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife to find the first reference to corn meal in the collection. She still called the dish Indian Meal Pudding, but in the text of the recipe she called it corn meal, a possible indication that new Americans were making the ingredient their own instead of holding it up as a native novelty. Four years later, A Lady of Philadelphia (later identified as Eliza Leslie) in her Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes and Sweetmeats added beef suet to the ingredients list – pushing the dish to the savory side. Leslie explained how a cook must leave room in the pudding’s muslin wrap to account for the meal’s swell during cooking, and suggests that left-overs were best eaten fried. Both treatments confirm an understanding that comes only from making the dish a great deal.

It wasn’t until 1832 that I could find the first reference to corn itself in the collection, in a book called The Farmer’s Own by H.L. Barnham. I didn’t find it in the recipe index but in the agriculture one, under a listing regarding curing corn that had turned musty before a farmer could feed it to the fowl, not the family.

On the title page of Sylvester Graham’s A Treatise on Bread and Bread Making printed in 1837, I found a lovely embossed stamp expressing ownership by a homeopathic physician in Keene, New Hampshire. Not really a receipt book, but rather a long essay on where and why bread fits into a healthy diet, the only thing that Graham had to say about bread made of Indian Corn Meal, as he refers to it, is that while it’s very good for you, it’s really only palatable with a lot of butter or other animal fat in the mix.

Indian Corn Meal hits the big time in an 1847 edition of Eliza Leslie’s The Lady’s Receipt Book where it gets front-of-book billing in the weights and measures conversion chart, listed second only to wheat flour. Under C for corn in the index, I found a page number for where I could get advice on removing a corn from my foot. I had to look under P for pudding to find a link to both an “Excellent Corn Meal Pudding” – with a variation that included peaches – and a “Fine Indian Meal Pudding.” The latter was made finer with a glass of brandy.

In the books published in the 1860s, there are still Indian Pudding receipts taking on additions like whortleberries and chopped apples, the more interesting cornmeal developments involved fewer time-intensive instructions for things like Griddle Cakes and Johnnycakes. In this timeframe, cornmeal moves into the realm of portable fast food, custom-made for Union and Confederate soldiers on the march during the Civil War.

By the time the Beecher sisters, Catharine and her sister Harriet (of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame), jointly wrote The American Woman’s Home in 1869, a general guide for domestic goddessery, Indian pudding was back to its basic form, plus or minus an egg or two. But corn itself was making its mark as food fit for humans in dishes like Green Corn Pudding, where unaged corn was taken from the cob and baked into sweet custard.

Around the turn of the 20th century, cookbook authors tried to move Indian Pudding away from its “old staple” reputation with additions of ginger (Fanny Merritt Farmer, The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book) and tricks like slowly stirring the Indian Meal into a cream custard (Maria Parloa’s recipe for “Delicate Indian Pudding” in The New England Cookbook in 1905).

But by the late 1920s, Indian Pudding fell off the map, possibly due to the rise of packaged puddings in popular flavors like chocolate, with more desirable silky textures and significantly less cooking times. In terms of the Kramer collection, the recipe was still included in general cookery books like The Joy of Cooking and community cookbooks where ladies would submit age-old family favorites with a twist or two so as to not be outdone. But other cookbooks from that era were hitting on niche markets with recipes for waffles, coffee, famous restaurant specialties, and casserole cookery.

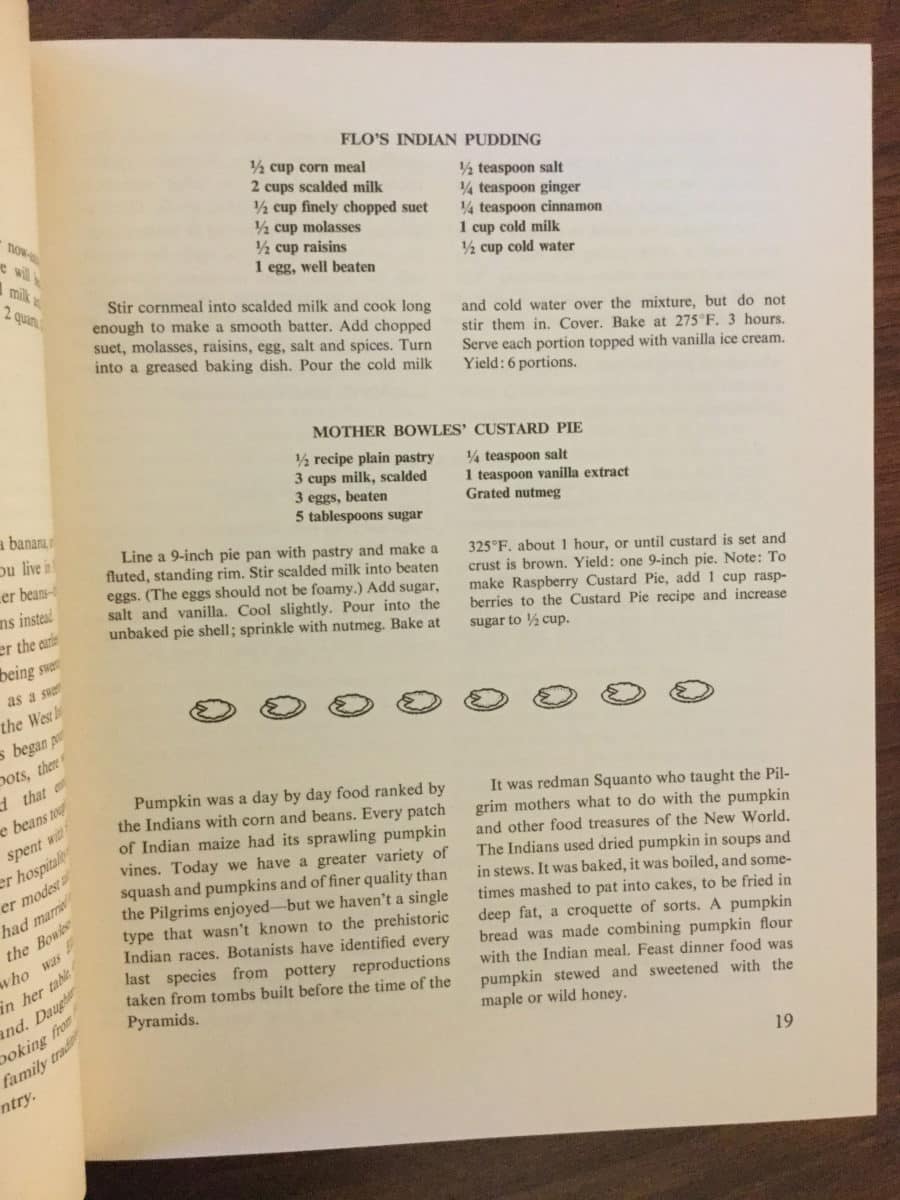

By the time Clementine Paddleford transported me across the country in 1960 with How America Eats, she could offer up recipes for Indian Pudding: a southern version served in Kentucky; a basic Yankee one from Massachusetts; and one called Flo’s Indian Pudding, passed down to Ella Bowles of Franconia, New Hampshire, that includes both suet and raisins and is served hot with vanilla ice cream.

Seems like a good place to end any journey, whether in time or space.

If you’d like to embark on your own time travel project, Bowdoin College Library special collections are open 9AM to 5PM, Monday through Friday. ![]()