In the grand courts of Renaissance Italy, food was more than sustenance. It was power, theater, and art all rolled into one. Among the most dazzling displays at banquets was the gilded roast—a pheasant, capon, or kid shimmering as though forged from gold. To modern eyes, this might seem excessive, but to the chefs and courtiers of the 16th century, it was a declaration of wealth and magnificence.

Bartolomeo Scappi, the famed papal chef and author of L’Opera (1570), documented hundreds of lavish dishes designed to astonish the palate and the eye. In his world, a gilded capon might be paraded into the banquet hall on silver platters, presented with ceremony and perhaps even accompanied by music. These were not everyday foods. They were culinary showpieces, reserved for popes, cardinals, and the elite of Italian society.

Gold-covered foods held deep symbolic value. Gold, the incorruptible metal, was associated with divinity and nobility. Serving it signified generosity, status, and divine favor. Hosts used gilded dishes to honor their most important guests, communicate power, and elevate their standing. In some cases, edible gold was believed to hold medicinal properties or invigorating qualities, though today we know gold is inert and tasteless. Scappi’s banquets reflected these beliefs. His menus, some containing over 100 dishes, often highlighted gilded items reserved for high-ranking guests. Accounts from the period describe spectacular scenes: soups with gilded sweetbreads, pies topped with gold leaf, and roasts that gleamed under candlelight. In one notable banquet, even the brooms used to clean the hall were gilded—an almost comic level of extravagance that drove some cities like Padua to enact laws limiting the number of gold-covered dishes at weddings.

The act of gilding meats could be achieved through two primary techniques: actual gold leaf, or a golden glaze made with saffron and egg yolk. The most luxurious approach was to apply ultra-thin sheets of edible gold directly onto the meat. Gold was hammered so thin that a single coin could yield hundreds of leaves. Cooks gently laid these over the surface of roasted meats, creating a visual illusion that the food itself was solid gold.

The more common method, however, was a technique that involved brushing the meat with a mixture of egg yolks and saffron. This not only imparted a warm golden hue but added a rich aroma and subtle flavor. Once painted, the meat would be returned briefly to the fire to set the glaze, creating a glossy, golden crust. The use of saffron, imported at great cost, reinforced the association with luxury.

Sometimes cooks combined the two methods. A roast might be brushed with saffron for overall color and then adorned with decorative patterns of gold or silver leaf. Dishes described in banquet records include gilded calves’ heads, meat pies with golden lids, and pheasants re-dressed in their own iridescent feathers, touched with gold for added brilliance.

The presentation was as important as the preparation. Banquet food was meant to awe. It was often tied to allegory or performance, arriving with symbolic flair. In Renaissance Italy, spectacle was part of the social contract of dining. The meal reflected the host’s cultural sophistication as much as their resources.

Although gilding may seem indulgent by today’s standards, its cultural context helps explain its appeal. The Renaissance valued magnificence—a virtue described by philosophers as the appropriate use of wealth for public display. A golden roast wasn’t just a feast for the stomach, it was nourishment for the eyes, the ego, and the soul.

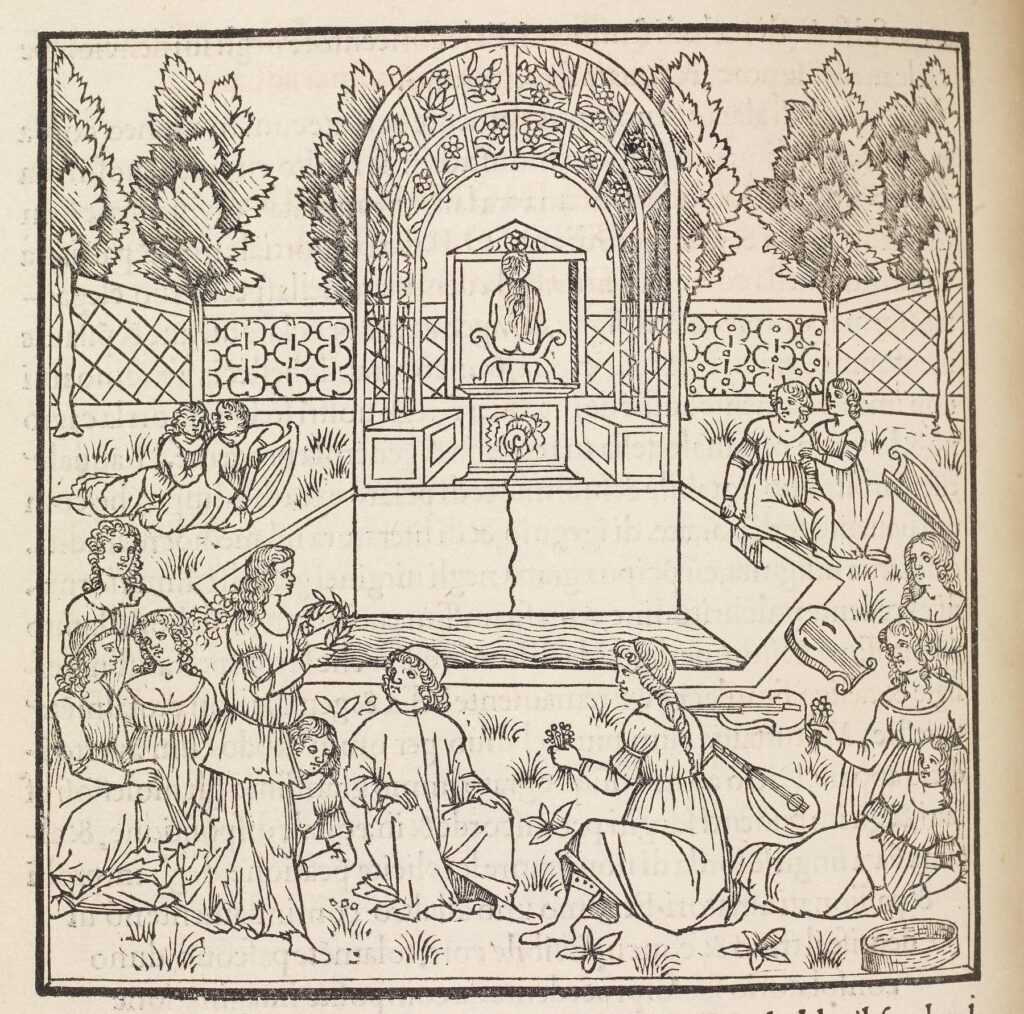

A recipe for gilded capon appears in my novel, In The Garden of Monsters, during one of the sumptuous banquets enjoyed by the characters. The inspiration for this dish comes from a medieval novel, The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili by Francesco Colonna, although Scappi also regularly gilded meats in his banquets. My second novel, The Chef’s Secret, explores the life of Bartolomeo Scappi, so of course I turned to his cookbook when I was recreating this dish.