Grandma cherished family meals. To her, “family” was anyone she cared for, and that included friends and neighbors.

This Is How It’s Done

In every young cook’s life there are experiences that show us this is how it’s done. When I was a child I observed two ways of entertaining, and these impressions informed me about hospitality in ways that have not been shaken into adulthood.

My parents entertained their friends with small elegant parties, soft jazz on the record player, and beautiful platters of French and Spanish-influenced hors d’oeuvres made by my father. We children were introduced, in our pajamas, to perfumed women in spiked heels and slim black dresses and men in shiny shoes, then sent off to bed to fall asleep to the hum of conversation against a background of Dave Brubeck. The word party still brings to mind cocktails clinking in ice and food on crackers.

But once a week, from my earliest memory until I was well into my teens, there was a party to which we kids were invited: family dinner at Grandma’s house. Grandma was my father’s mother. She cherished family meals. To her, “family” was anyone she cared for, and that included friends and neighbors. And it was a party, every week, every time.

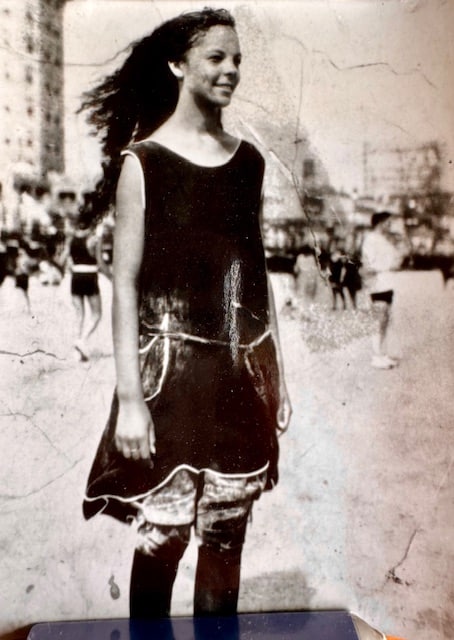

To get there, my younger brother and sister and I would travel with our parents on the elevated subway from the edge of the Bronx to my grandma’s apartment in Manhattan. The open-air subway platforms were worn wooden boards and my mother’s high heels would catch in the spaces between them. The subway seats were woven tan rattan or dark red leatherette, and each pair of opening and closing subway car doors had the words Please Keep Hands on the left door, and Off the Doors on the right.

Dressed nicely, with our hair combed, we rode the rocketing train for about 20 minutes, then Grandma’s building complex would come into view.

Fried Chicken and Collards

Grandma could cook but she didn’t spend a lot of time on it. She was a busy woman, teaching public school second-graders full-time, involved in her church, and caring for a husband wheelchair-bound and severely crippled with rheumatoid arthritis. She cooked everyday foods, but, once a week, Grandma hired Gladys to cook a family meal and the menu was always the same. Crunchy fried chicken, mashed potatoes, collard greens cooked with smoked pork, green beans cooked with salt pork until soft and flavorful, stewed blackeyed peas (more pork), salad, cornbread, biscuits and gravy. Dessert of lemon meringue pie or banana cream pie, often both.

A typical Thursday night dinner would feed a dozen people, sometimes more. They included neighbors from her apartment building, like Mr and Mrs Sapp. Mr Sapp was a retired airline pilot and I thought he was rather handsome. He had a plump round wife who died without giving notice and a short time later was replaced with a new Mrs Sapp who, to me, was almost indistinguishable from the first. There was Aunt Bea, whom I disliked, who had a loud raspy voice, intrusive cologne, numerous jangling bracelets, and who was always holding a whiskey glass with red lipstick smudged at the lip. There was Ruth, a whispery neighbor from down the hall, who was so blind she had to be led anywhere she went, but when taken to the lawn in front of the building could pick out – I witnessed this – one 4-leaf clover after another.

I loved Grandma’s sister, Aunt Elyse, an independent woman who laughed often, and her daughter Carol, who was eight years older than I and therefore a grownup in my eyes. Sometimes other family members were visiting from out of town. My dad’s sister, who lived in glamorous Washington DC, was a vocalist and taught us songs from My Fair Lady and other shows. Her husband was lanky and casually stylish, and my brother and sister and I adored our cousins, Kathy, my age within one week, and her brother Richard, a few years older. We five kids would find corners of the apartment where we could huddle on the floor, telling jokes and making fun of the adults.

Pot Liquor, Poetry, and Mashed Potatoes

Maybe I am imagining the memory of smelling fried chicken when the elevator door opened on the 21st floor. We would fly down the long hallway to Grandma’s door, our shoes clattering on the linoleum. Just inside the apartment was a long hall table with a black china panther lounging on it, which I always stopped to admire and pat. Coats got piled onto Grandma’s bed. The living room was filled with one long table and many small ones. We crowded into the small kitchen to greet Gladys and beg for tastes. Dinner would be served soon, but we were allowed a special treat that my dad would hand out – the “pot liquor” from the collard greens. We were starving at that point and the liquid, dished out to us in tea cups, tasted heavenly and held us over while plates were served. My dad told us, every time, how nutritious it was.

There was a prayer before dinner. Voices rose, poetry was recited over mashed potatoes and biscuits. There was much raucous laughter and stories were told as if these same people hadn’t seen each other a week before or would likely meet again in seven days. We kids finished eating first, and if we asked to be excused no one heard or paid us any mind. We slipped to the floor and crept back to the quiet of Grandma’s bedroom, petting the fur coats and looking through the huge “junk drawer” we were allowed to explore.

Later, dazed, fed, kissed goodbye and feeling loved, we were led back to the subway and the ride home, happy in the knowledge that we would be back next week. ![]()