How a railway car shaped the concept of bread in the American imagination.

The square, tasty bread served on all Pullman dining cars became both ubiquitous and fashionable. Enhanced by the coincidental similarity between the bread and the recognizable shape of the Pullman car it became universally known as the Pullman loaf.

During the pandemic, a lot of people who had never baked bread discovered the wonder and magic of creating their own loaves from scratch. Those who had made bread occasionally were now making it on a regular basis, and for a while there was even a shortage of flour and yeast. Jars of sourdough starter were, well, started, and then pampered like house pets. The presence of active starter served as motivation and ease of frequent baking. After this period of intensity waned and dry yeast returned to store shelves, many are happily still making bread.

Boules, with golden brown crusts emerged from ovens, with open crumb interiors full of rich flavor and aromas. With burgeoning confidence, home bakers turned out baguettes and batârds. Some moved on to brioche, challah, even lard bread. It didn’t take long to discover a wonderland of bread possibilities.

But few made sandwich bread, the true classic “Pullman” loaf.

This sturdy, ultimately defining loaf, called pain de mie was born in the eighteenth century. But it got its American moniker from nineteenth century steam-driven railway cars. The Industrial Revolution was powered by steam, and the locomotive was the outsized symbol of that power. When the principles of locomotion were applied to the mechanization of hand-worked goods it changed not only how things were made, but promoted urbanization and literacy, and influenced language and global culture.

When railroading arrived, nothing would be the same again. Pretty soon travel by rail became desirable, a luxury for some, a utility for many, and it was there, due to the genius of George Pullman, that pain de mie found a new home, and eventually a new name.

The Pullman Loaf, bred to travel

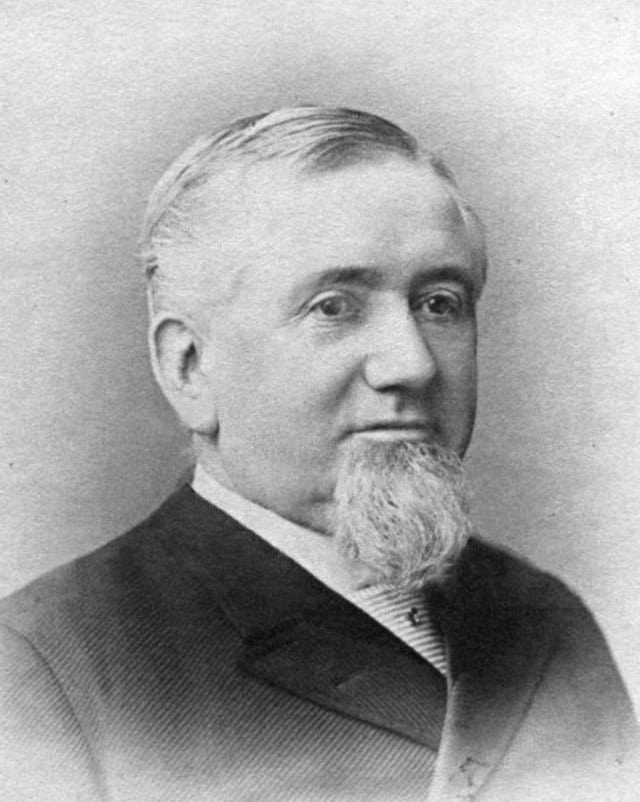

George Mortimer Pullman grew up in Albion, New York adjacent to the Erie Canal. Here he had witnessed the evolution of ever more refined water borne vessels, packet boats, transporting passengers back and forth.

Part of the success of canal trade, and passenger traffic, got a boost when Pullman’s father invented a jackscrew that was used to raise entire buildings to relocate them so the width of the canal might be expanded to facilitate increasing commerce. It was this invention, and skill that the father passed on to the son, that George Pullman took with him to Chicago. In 1857 he was involved in building the nation’s first comprehensive sewer system that required raising, and moving (with the aid of the jackscrew), a number of buildings including the massive Tremont Hotel with the amazed resident guests within.

This idea of a rolling hotel would apparently stay with Pullman, consciously or otherwise.

From rudimentary to rarified

Traveling by train by the middle of the nineteenth century was still somewhat rudimentary. Too rudimentary for George Pullman. Trains were more about conveyance than comfort. Longer journeys and overnight trips were distinctly distasteful. Insightful, inventive, detail-oriented and imaginative, George Pullman rightly thought that there was a market for a more accommodating train car — a sleeping car as commodious as the fine canal vessels of his youth, indeed as engaging and well appointed as a fine hotel. On wheels.

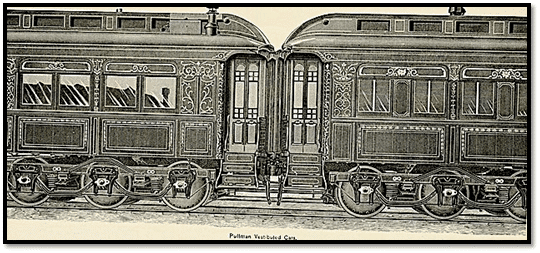

The first full iteration of his concept and design, the Palace Car, appeared in 1864. Longer, higher and wider, it set the bar for all that was to come. “Furnishings included black walnut woodwork with inlay, framed mirrors between the windows, French plush upholstery, polished brass fixtures, good beds, ample bedding, deep pile carpeting on the floor, somewhat influenced by the furnishing of the saloons and cabins of the river steamboats.”(railswest.com)

A year later, as part of his funeral train in the very car he had commissioned, President Lincoln’s body was transported from Washington D.C. to his resting place in Springfield, Illinois. Hundreds of thousands of mourners lining the route bore witness. A brand was launched.

In 1867, Pullman’s “hotel on wheels” concept was more fully realized when the car called “The President” debuted. Pullman brought elegance to the railway car, with brass fittings and lamps, velvet, tufted and tasseled seating, fine woodwork and marquetry, and magical drop down sleeping berths wrapped in fine linens.

From a dining car kitchen came bread perfection

Most importantly a dining car with a full (if somewhat cramped) kitchen with professional chefs and a highly trained serving staff was added. A year later the “Delmonico,” named for New York City’s famed bastion of haute cuisine, took the fine dining-on-wheels concept a notch higher.

Because every inch counted in a Pullman kitchen, every height, width and placement was carefully calculated for utmost efficiency, and storage space was critical. It was no surprise that Pullman was delighted by the shape of a loaf of Pain de mie bread. Also called Pain Anglais, it is a sturdy symmetrical four-square loaf with a tight, fine crumb, and compelling flavor. The mie (crumb) in pain de mie puts the emphasis squarely (so to speak) on crumb over crust. To accomplish this physically constrained, tanned brick of delight, eighteenth century Boulangers placed the risen dough in a rectangular metal box fitted with a sliding lid for its second rise. The dough could only grow to the dimensions of its box and therefore produced an even, slightly dense interior. It was bread perfection — at least, geometric perfection. Other, unrestrained, loaves of bread when baked freely rose in the pan into a happy domed top. Not only was the flat-topped, pain de mie stackable, to Pullman’s delight, four could be stored in the same space as three precarious round topped loaves. The age of efficiency pre-figured.

A bread gets a new name

Before long Pullman cars were being produced in the hundreds, with endless amenities, eager-to-please porters, barbers, manicurists, typists and more — luxury train travel became nearly as desirable as the desired destination. The Pullman name stood for excellence in every aspect of train travel. Remarkably, The Pullman Company that lasted over a century was never a railroad. It did, however, build, staff, and lease its Pullman sleeper, parlour and dining cars to railroad companies like the Pennsylvania Rail Road, Union Pacific, and Baltimore & Ohio Railways.

The interior design, décor, and sophistication of the Pullman experience became widely influential. The narrow, no-inch-wasted galley kitchens live on in the term for similar spaces in small apartments called Pullman kitchens.

The square, tasty bread served on all Pullman dining cars became both ubiquitous and fashionable. Enhanced by the coincidental similarity between the bread and the recognizable shape of the Pullman car it became universally known as the Pullman loaf.![]()