That bottle of wine you don’t drink at home because it’s too good or was a special gift should have its day. Many of us keep bottles because we think we need a special occasion to drink them or because they mark a happy time we want to repeat someday.

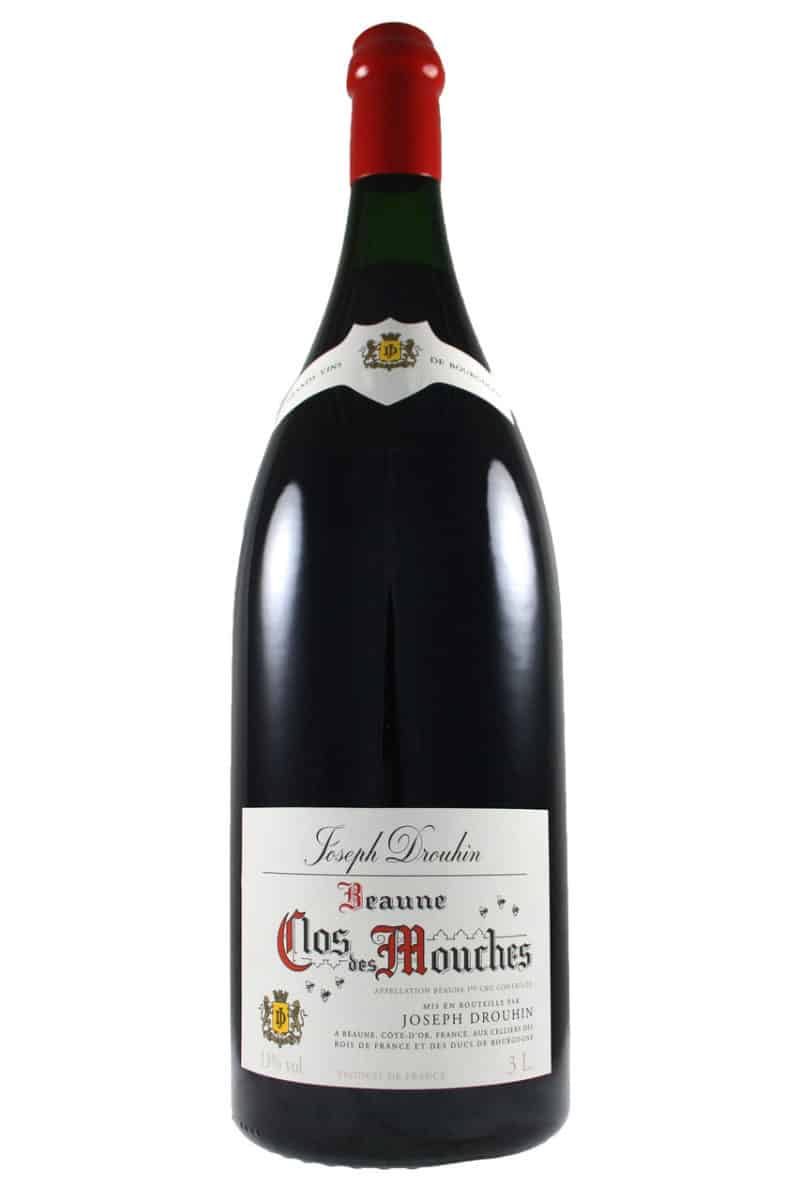

Sentimentality kept me from drinking my collection of Maison Joseph Drouhin Beaune Clos des Mouches reds. In the early ‘70s my wife, then girlfriend, Brenda Baker, and I had a date at a little restaurant in Greenwich Village. We ordered a bottle of Maison Joseph Drouhin Beaune Clos des Mouches red, a wine we had not had before. I tried it because I had tasted a few Burgundies and liked them — and, frankly, because I thought the artistic label with the bees flying around grapevines was attractive. It was a revelation. Big cherry flavors with a soft but pleasant acid balance and sweet notes of Asian spice filled our mouths. The wine went well with the country pate and roast chicken. I think it was the ’69 vintage, a year noted for its warm, sunny summer and ripe grapes. The wine made for quite a romantic evening.

The wine stuck in my mind and, when I started having enough money to do so, I collected some of every vintage. The chance to try some of them arose when a group of musicians and wine lovers came over to our house after a concert played at SummerFest, the music festival of La Jolla Music Society in La Jolla, California, where our house overlooks the Pacific.

I decided on a partial vertical of the 1993, 1996, 1999, and 2000 vintages. Verticals are fun because one can taste the differences in different years of the same wine. I added the 2003 at the end to compare to some 2003 California pinot noirs because summer 2003 in Burgundy, as in the rest of Europe, was the hottest in memory with the earliest harvest in Burgundy in 150 years. The critics are split in their opinions of this vintage, some saying it will evolve to be a great vintage on the order of 1959 and 19291. Others have said that the 2003 Burgundies are atypical and resemble the bigger pinot noirs of California which have dense, jammy fruit and lower acidity.

The wines had been cellared since their purchase at 14°C (58°F) and were opened about an hour before the tasting2.

First to be tasted was the 20003, which was ready to drink, balanced, with supple berry and cherry flavors.

Next came the 1999, still evolving, with more noticeable acidity and density than the 2000. Warm flavors of blackberries and earth prevail. It will improve over the next several years as it gains complexity.

The 1996 showed its characteristic tannic structure and was still a little closed. It had density and intense berry fruit but will need 3-5 more years to open fully. Tannins can often be bitter in young wine but evolve into softer and sweeter components with time. When the tannins soften, a wine may be said to open.

The 1993 opened generously with earth, spice, and sweet berry fruit. It had a looser texture than the other wines and is fully ready to drink. Texture is the way the wine feels in the mouth and can range from thin and watery to thick and syrupy. It should feel well knit.

We then came to the 2003. It was dense, alcoholic, with a chewy texture, tasting of intense dark fruit with a licorice undertone bound by slightly bitter tannins but with relatively low acidity. It should continue to evolve for many years. We compared it to a 2003 Kistler Vineyards Sonoma Coast Pinot Noir and a 2003 William Selyem Russian River Pinot Noir. Both were more dense, intense, and alcoholic than the Clos des Mouches with volatile overtones and a burnt sugar element, although they were not sweet.

The group split as to its favorites with a plurality choosing the 1999 Clos des Mouches. Everyone picked the 2003 Clos des Mouches over the two California pinot noirs, which seemed too big and hot in comparison, although tasty in their own right.

The flavors and aromas of the various Clos des Mouches brought back to my wife and me that romantic evening in New York so many years ago, much like Proust’s memories evoked by the taste of madeleines he described in A la recherche du temps perdu.

Maison Joseph Drouhin Beaune Clos des Mouches Rouge comes from a premier cru vineyard of the same name located mid-slope on a slight incline, facing southeast, at the southern end of the village of Beaune next to the village of Pommard. The name comes from the early use of the site for bee keeping, the name having been shortened from mouches de miel, honey flies. Large by Burgundy standards – 36 acres – it is planted half in pinot noir and half in chardonnay. Interestingly, the Clos des Mouches blanc gets higher ratings and commands higher prices than the rouge, as the soil seems to favor chardonnay over pinot noir. Grown according to biodynamic principles, the grapes are hand-picked and fermented in French oak barrels, 20% of which are new. Widely available, Joseph Drouhin Clos des Mouches red averages about $90 a bottle, although prices vary. If it’s not available from your local wine merchant, ask the merchant to order it from its wholesaler or from the importer, Dreyfus, Ashby & Co., New York.

Footnotes:

1 The 1959 and 1929 vintages both had warm springs and hot summers. The grapes had lower than usual acidity but strong tannins, which acted as a preservative.

2 13°C (55°F) is the usually recommended temperature for wine storage as it replicates the temperature of natural underground cellars. Higher temperatures will cause wines to mature more quickly. Lower temperatures will slow the maturation. Of course, high temperatures, greater than 27°C (80°F), even for a few days, will spoil wines. I choose 14°C (58°F) because I intend to drink my wine a bit sooner. By sooner I mean after 10 years for most good, red Burgundies rather than 10-15 years at 13°C (55°F) or much longer for wines stored at lower temperatures. I have a very sophisticated wine friend who stores his wines at 50 degrees F. because he prefers the freshness and bright acidity kept by the lower temperature. He is younger than I so he can wait longer. Whatever temperature one chooses, the thing to avoid is very high temperatures or rapid changes in temperature, which both damage wines.

3 What does “ready to drink” mean? Of course, most wines are made to be drunk young and are drunk soon after their vintage year. Fine Burgundies like Drouhin Beaune Clos des Mouches are made to be best appreciated after some years of cellaring so that their acidities and tannins diminish and the wines develop weight and complexity, including secondary flavors such as spice, earth, mushrooms, etc.. They are then “ready to drink”.

More about Burgundy wine:

Burgundy wine is regulated by the French government’s INAO (Institut National des Appellations d’Origine), which requires a hierarchical order for the names designating where a wine is grown. The hierarchy generally denotes quality but there is certainly overlap.

At the bottom is simple Bourgogne, which can come from anywhere in Burgundy and can be blended from different sites. Next up the ladder are regional designations such as Cote de Beaune Villages or Cote de Nuits Villages, requiring the wine to come from villages in those regions. Next up are village wines, which may come from different sites within each village, for example “Beaune.” Next higher is premier cru or “first growth.” This must come from a particular named premier cru vineyard within a village and also carry the village name like “Beaune Clos des Mouches” and the designation premier cru, or it may come from a blend of premier cru vineyards within a particular village and simply be called, for example, “Beaune Premier Cru” without any vineyard name. Last and highest is Grand Cru, “Great Growth,” of which there are only 32 in all of Burgundy.

Grand Cru is a designated vineyard, and only the name of the vineyard appears on the label without the village name, although sometimes Grand Cru also appears. An example would be Chambertin or Romanee Conti. If any differently designated wines within these ranks are blended, they must take the name of the lowest rank. For example, sometimes in poorer years when there may not be enough of a grand cru to bottle, it might be blended with a premier cru of the same village but the wine must be called only premier cru without a vineyard name. If it is blended with any wine outside the village, the wine simply becomes Bourgogne.

Prices rise dramatically as the designations go up the ladder. A word of caution: just because the wine has a famous grand cru or premier cru named vineyard on the label doesn’t mean that the grower has made a good wine. There many different owners of most village, premier cru, and grand cru vineyards who are entitled to put the famous name on their wine. Some make great wine and some make awful stuff. Knowing the grower’s reputation is essential. ![]()