As far as fruit crops go, blueberries are a rather recent vintage, dating back to the early 1900s. Wild plants were transformed into domesticated varieties by a breeder at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in Beltsville, Maryland. Soon the forest plants that produced a few small tasty berries on low bushes became part of strategic genetic improvement and widespread cultivation as “highbush blueberry.” Blueberries are an important part of the American fruit landscape, and have the distinction of being one of the few fruits and veggies that actually originated and evolved in the modern day USA.

Acreage has increased in the last decades, driven mostly by improved varieties and year-round availability. Production acres continue to increase in Chile and Peru, Morocco and Spain. Mexico has a growing industry, and California, Florida and other North American production ensure continued availability of this important fruit.

Blueberries are coveted for their explosion of flavors, but also their potential health benefits. They are rich in vitamins, but they are prized for their abundant pigments that have potential roles in mitigating a suite of health problems.

However, blueberry faces some mounting production threats that may make price and availability a little less attractive. Scientists are working hard to develop creative solutions to ensure the future of the blueberry industry and its delicious fruits.

Blueberry trees?

Florida is the evolutionary home to blueberry. A careful hiker can spot its wild relatives on the edges of forests and on the banks of rivers where their deep roots anchor them firmly to the earth. One of its cousins, called “sparkleberry,” grows as a tree. It produces a tiny, gritty berry that does not have much taste. But sparkleberry thrives in Florida’s sandy soils, producing extensive and deep root systems that evolved to capture sparse nutrients and inhospitable basic limestone pH conditions.

In Florida cultivation, blueberries are grown in mounds of pine bark, providing the acidic conditions the plants love. Farmers irrigate with drip tubes that deliver water and nutrients directly to the root area. The water and fertilizer solution also contains sulfuric acid, added to make the soil more acidic and conducive to what the cultivated varieties want.

Is there a way to get the sparkleberry’s durable deep roots matched with the production of the modern cultivated blueberry? Plant breeders could make the crosses and try to breed for improved roots and excellent fruits. The problem is that good roots come from a plant with useless fruits, so finding a plant that would have both beautiful tree roots and high quality fruits is a needle in the genetic haystack.

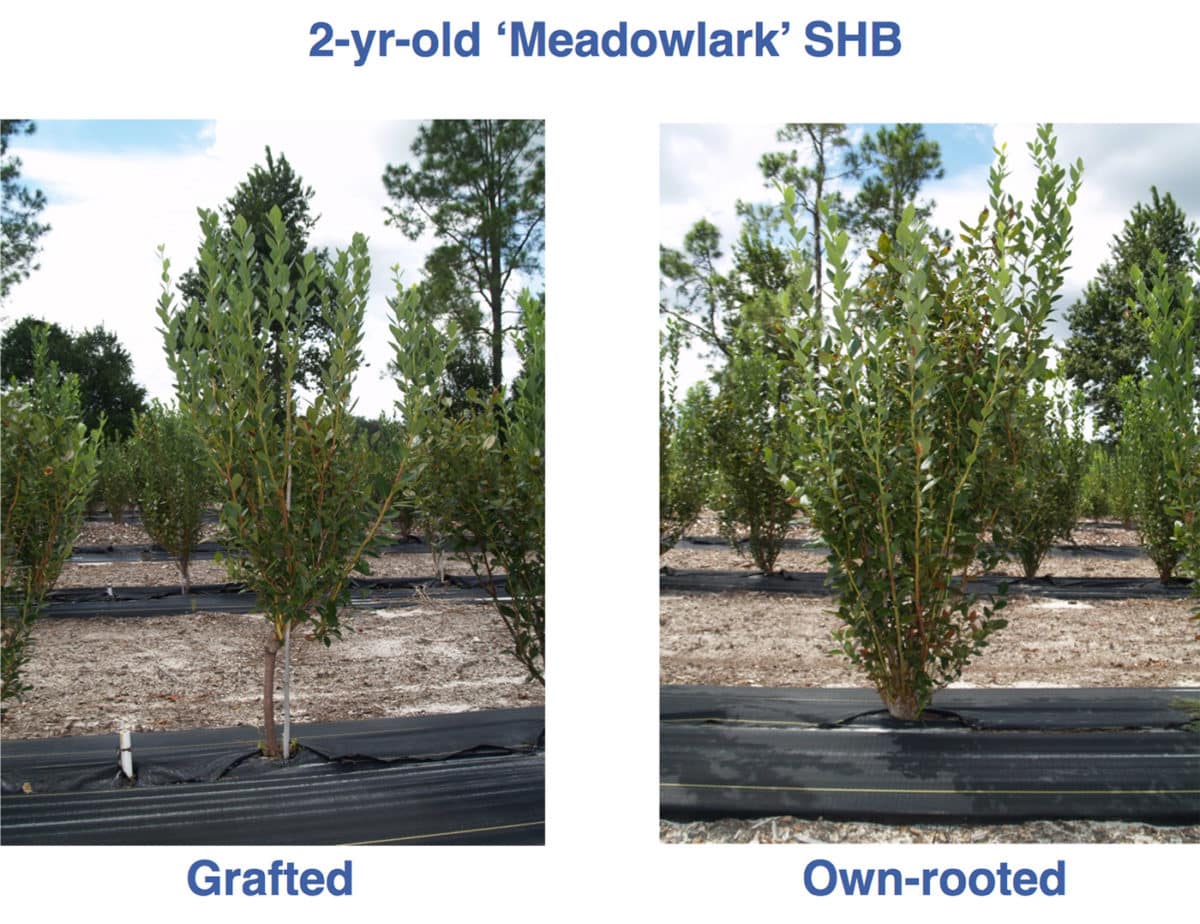

The idea of making a hybrid tree could happen with genetic crosses, or it could happen even faster by simply grafting the productive blueberry variety directly onto the sparkleberry roots. This plant would have a single trunk with the deep roots of the adapted tree, topped with the high-fruit-quality scion of a modern fruit variety. Who says blueberries don’t grow on trees?

The real beauty of the blueberry tree is that the single trunk can also help solve an important problem — labor. Finding hands to manually pick berries is a difficult task, so more and more farmers are turning to machine harvesting. The stout single trunk provides a better base for tree shaking (to break loose the berries) than a cluster of canes, which can break or not shake evenly.

So while blueberry bushes will always be the norm in most places, in Florida blueberries just might be more common on trees. The grafted plants can offer more options for harvesting, resistance to root diseases, and still produce the outstanding berries grown in the Sunshine State.

Courtesy photo

Enter the Deer Berry

Most people never notice when you take a bite of a blueberry the inside is actually white. The purple compounds (known broadly as “anthocyanins”) of the blueberry reside in its thin skin. These colorful pigments make fruits attractive, both for fresh consumption and in cooking. But as mentioned earlier, these compounds have become coveted for their potential effects on health.

Scientists have poked around the forests where the blueberry was born. Consistent with evolutionary trends, if blueberry is present, other similar plants must have adopted similar strategies and products.

Enter Stamineum, a plant from the same family as blueberry, cranberry, and bilberry (Vaccinium) that also is found throughout Florida’s northern forests. Stamineum is familiarly known as “Deer Berry,” a fruit that has unusual flavors and high sugar levels. It is a favorite of bears, probably deer, and almost certainly was a fruit consumed by indigenous people. But most importantly, the deer berry has anthocyanins distributed throughout its flesh, not just in the skin as seen in blueberry.

So why don’t we eat deer berries instead of blueberries? It is a question of domestication. Just as dog breeds are the result of domestication of wolves, just about every plant product you eat is a result of humans domesticating a wild species to perform better for our benefit. Some of the desirable traits that humans look for are fruit size, yield, disease resistance and high quality after shipping.

While the deer berry has beautiful pigments and high sweetness, it has numerous shortcomings that preclude its use in agricultural production. One of the big problems is that the fruits fall from the plant very easily, which means even a gentle rain or strong breeze could drive yields to zero. It also does not like to make roots from cuttings, making propagation difficult.

Enter Dr. Paul Lyrene, Professor Emeritus at the University of Florida. Dr. Lyrene has performed genetic crosses between the standard southern-highbush blueberry and the deer berry. Commercial blueberry brings high yields, disease resistance, and retains the fruit on the plant before harvest. Deer berry brings pigmented fruits, and a deep root system that grows well in sandy soils.

Dr. Lyrene makes the crosses and lets genetic shuffling take over from there. Plants of the next generations will mix and match these traits to various degrees. Plant breeders like Dr. Lyrene monitor the inheritance of these traits, and then plan additional crosses. Sometimes they will cross back to one of the parents, other times to a genetic sibling, other times to an unrelated plant that has especially strong traits of interest.

The goal is to move the genes encoding all of these important traits into one common plant background. It is a bit like strategically shuffling a dozen decks of cards and getting all of the aces on the top of the pile. Of course, plant breeders are guiding which decks to shuffle, and sometimes throwing some deuces from the deck, so it is not just a random process. Still, the development of a commercial quality blueberry-deerberry hybrid could be years away.

Future of Fruit Innovation

Blueberry trees and Deer Berry hybrids are just two of the ways that scientists are defining the future of fruit. For the consumer it is a reminder that fruits and vegetables are really rare gifts of nature that humans have carefully changed to meet our grandest production challenges. The future looks bright for blueberries, as new production tricks, like grafted trees, and new traits borrowed from a genetic cousin, will provide improved varieties for consumers. ![]()